For I am every dead thing,

In whom Love wrought new alchemy.

For his art did express

A quintessence even from nothingness,

From dull privations, and lean emptiness;

He ruin’d me, and I am re-begot

Of absence, darkness, death: things which are not.

— John Donne, ‘A Nocturnal upon St Lucy’s Day’

Haiti exerts magic over all those who are lucky enough to know something of this country. (This statement is no vulgar reduction of Haiti to an essentialised response to ‘voodoo’, but a full acknowledgement of the revolutionary power and enchantment of ‘vaudou’).

I am one of those fortunate people. Last November I got to spend some time in Port-au-Prince. Already familiar with the energies of Haitian music and its revolutionary history, it was nevertheless necessary to be in this city to absorb the astonishing creative energies of its people, who constantly re-fabricate the dark things of life without ever making anything saccharine sweet. In Port-au-Prince, creativity and autonomy co-exist side by side and the most ordinary, waste materials of existence are converted into objects that enchant while they terrify. Haiti allows us to keep the dark side of human nature in the foreground while celebrating resilience.

It is true that Modern Moves focuses on Afro-diasporic music and dance. But it is not possible to isolate these social phenomena from other forms of creative expression. In Port-au-Prince, I felt visual art, rhythm, and spirituality were vitally connected to each other and in a dynamic relationship to the market economy. When I realised that Grand Palais in Paris was the venue for an ambitious new exhibition ‘Haiti’, showcasing 200 years of Haitian art, I lost no time in using the opportunity to self-educate myself further.

In this blogpost I present some of the photos I took at this exhibition with some comments. People near or in Paris should certainly make time to see ‘Haiti’, as it teaches us a great deal not only about Haiti, but, in the words of W. E. B. DuBois, ‘the souls of black folk’ and, in the process, something about humanity’s relationship to global modernity.

‘The ceremony is about to start’

Ceremonial portal through which visitors must pass to enter the exhibition

The ephemeral and modern materials- votive candles and aluminium- used offer an eloquent contrast to the ‘solidity’ of empire as seen in the architecture of the Grand Palais and its environs.

It was satisfying to be confronted, on entry, with images such as this one– which mixes icons of Catholicism, vaudou, modern music and dance culture, and traditional roots music– in a manner that confirms what we know of ‘Haiti’:

For those of us interested in the expressive capacities and symbology of ‘vaudou’, we could find both classic and contemporary representations of altars and gods, including references to Damballa, Ogun, and Erzulie.

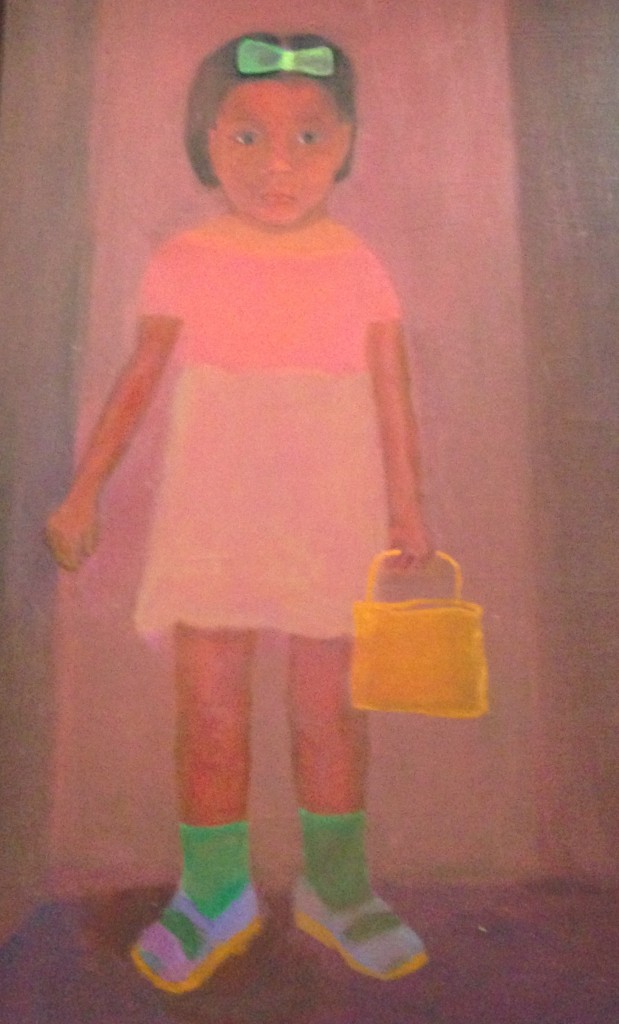

But it was equally important to be educated through glimpses of the ‘inner world’ of Haitian modernity, focusing on childhood, embourgeoisement, violence, and the terror and joys of intimacy.

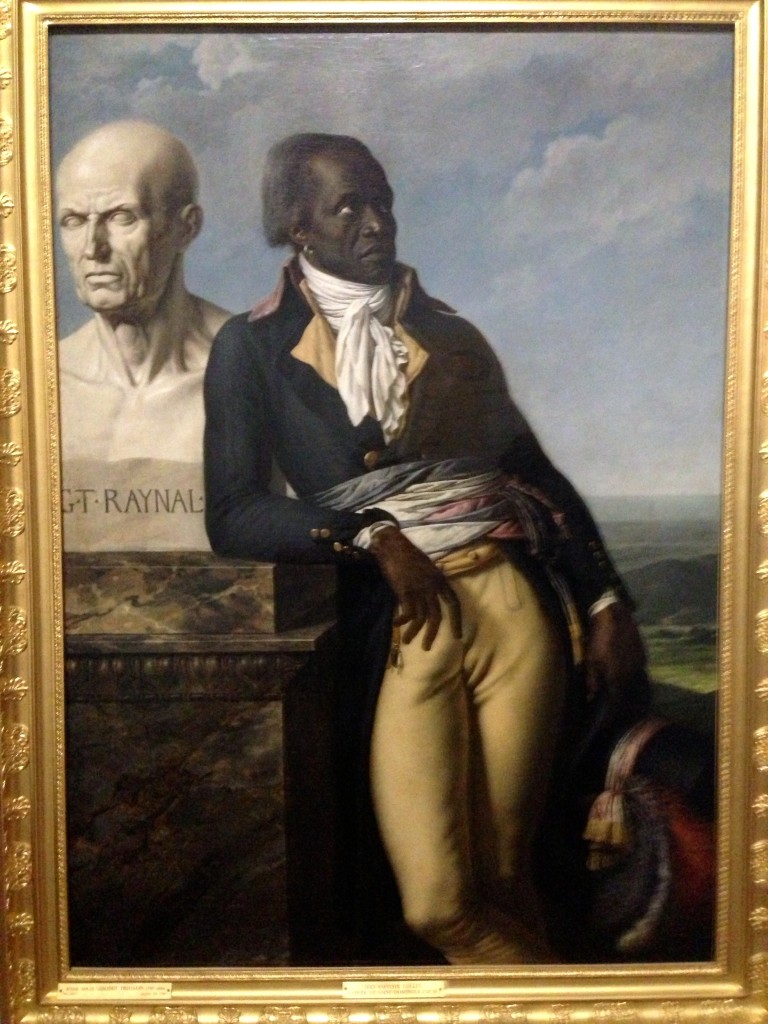

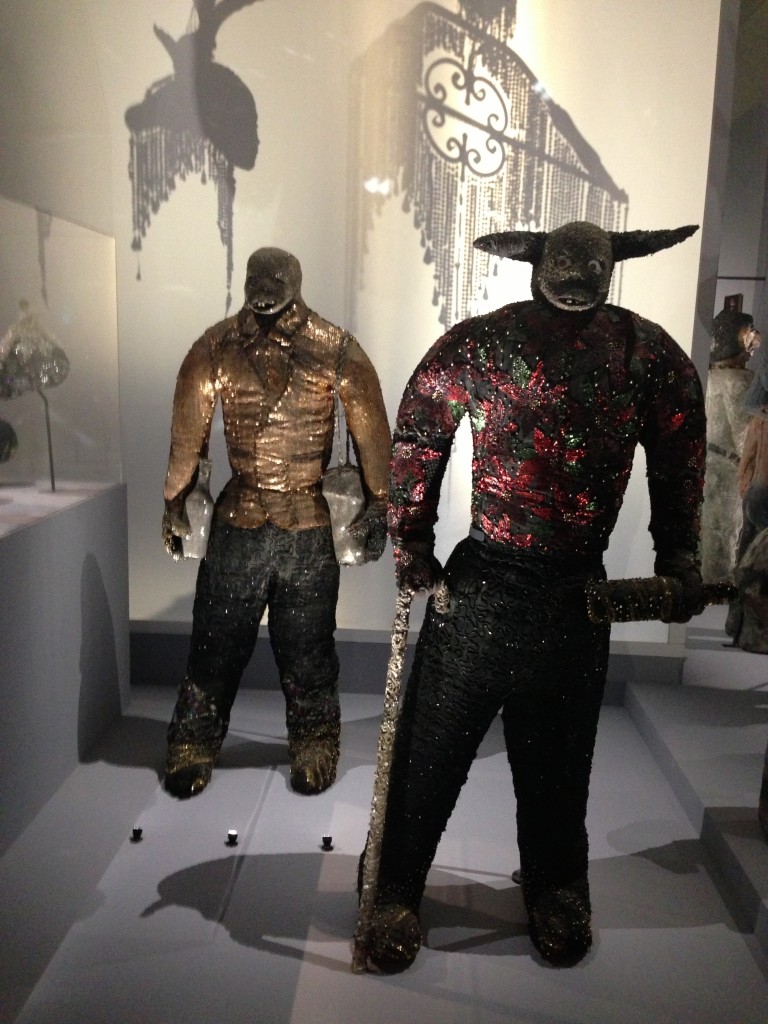

A cross-sectional view of the exhibits also allowed us to understand something about the enduring power and fragility of (and fascination with) black masculinity, from the earliest days of colonial portraiture to the work of the ‘atis resistans’ creating monumental statements that reclaim urban space in Port-au-Prince and whose impact is barely diminished on being caged in the Grand Palais.

sex, death and renewal are not subjects that Haitian art shies away from. The aesthetics of glitter and embellishment are liberally used to foreground their contiguity as the one truth about human existence.

Perhaps the most powerful exhibits for me were those artworks that demonstrated, celebrated and also lamented Haiti’s brave yet misunderstood place at the crossroads, indeed vanguard, of global modernity. This final sequence of images shows a) Edouard Duval-Carrie’s ‘L’emarquement pour l’Isle de France ou le renvoi d’Erzulie Freda Dahomey’ (2014), b) Henri Telemaque’s ‘Le Voyage d’Hector Hippolyte en Afrique’ (2000), and c) Jean-Ulrich Desert’s ‘Constellation de la deesse’ (2013) which recaptures the night sky over Port-au-Prince the moment the earthquake struck, through medallions struck with the visage of Josephine Baker, ‘the Black Madonna, the Divine Negress, the new Erzulie.’

Blogpost written after my visit to ‘Haiti’ at Grand Palais, 15th December 2014.

I thank Wilfrid Vertueux for his commentary and observations on the exhibition!