This past June, 2016, I went to do doctoral field research in Haiti. And oh my, what a month that was! In addition to my own research project, my fieldwork trip overlapped with Modern Moves’ participation in The Caribbean Studies Association’s Annual Conference entitled ‘Caribbean Global Movements: People, Ideas, Culture, Arts and Economic Sustainability’, June 5-11 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Here, I presented my paper in Modern Moves’ panel discussion ‘Staging a New Creolité: Katherine Dunham’s circum-Atlantic World’. After the rest of the team departed, I continued on to collect materials on textual and embodied representations of vodou and their significance in shaping afro-diasporic imaginaries and futurities. Endangered and elusive, it was my intent to see how the nation treats and engages with its vodou influenced past and treats it in the present to explore its contemporary manifestations, both in terms of the vodou practitioners as well as cultural and artistic expressions. I wanted to find the ruptures in which it recaptures the memory of a shared but disrupted past of the three abysses of estrangement, dislocation and relocation created during the Middle Passage.

It wasn’t my first time in Haiti, but much had changed since visiting in 2009 before the earthquake. It was also in an extended tense political climate due to the continuously delayed presidential elections which the majority of the country is at odds with. During my stay, the temporary president was urged to step down, a move to be followed by new elections which ended up not taking place. There was a rise in protests, in murders and robberies throughout Port-au-Prince and Petionville, where a lot of the violence was moving to revealing a tired and upset public engagement with governmental politics, which are strongly influenced by US involvement.

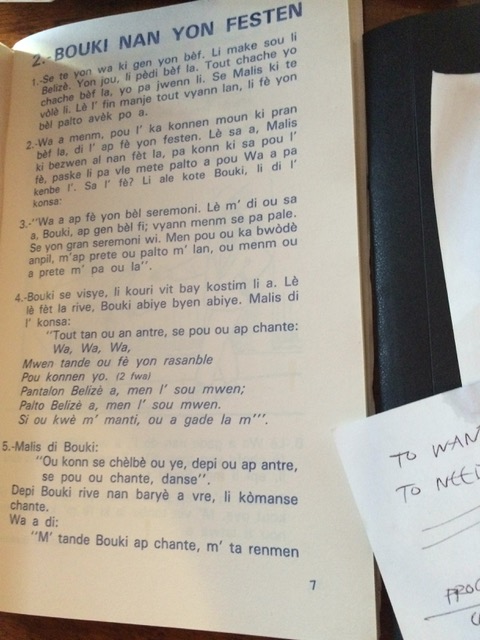

Obviously to navigate my way through communicating with people, learning Haitian Creole was on my agenda and took up a good amount of my time and mental focus. I managed to make my way through 1.5 levels of an overall 4 within the three and a half weeks I spent there, which provided me with a solid foundation. Still, a lot of my interviews and communication in general were in French and English but I felt much more confident moving around being able to speak the local language and what rhythm it has to it! Definitely want to complete all 4 levels which will prove significant to my overall research as the majority of Haiti communicates in creole and the entirety of vodou ceremonies are expressed in it.

Fear and endangerment of vodou stretches across spheres of society, despite close ancestors having been direct believers and practitioners of the spiritual system. Yet contemporary expressions of vodou and artistic approaches were everywhere to be found. The Centre d’Art had an incredibly diverse archive which approached the cosmology from all sorts of angles. I conducted the majority of my research at the Bureau d’Etnologie given the diverse approaches and political approach to dissemination of vodou practices and expressions. It was founded in 1941 by Jean Price-Mars, Haitian ethnographer, diplomat and writer who was the first prominent defender at a political level. His writings championed the Negritude movement in Haiti and embraced a national Haitian identity as African through slavery. The Bureau was conceived in the context of a renewal of interest in archaeology and the desire to safeguard cultural objects. and dedicated to the collection and study of material culture. The material culture of vodou has been a domain under researched, with few exceptions such as of the collection of Marianne Lehman, for example, which Rachel Beauvoir-Dominique has written about. This raises questions and concerns about new perspectives on the representation and creation of Haitian identity that embrace vodou. With Erol Josue as the newly appointed director of the Bureau of Ethnology, there has been a strong concern with documenting and preserving the material culture of vodou, which in previous years had not been a priority on the agenda. There was a significant amount of research archived that underlined the penalisation of vodou from the colonial period until recently. Despite being recognized as a religion in the 1930s, it remained juridically prohibited until the Constitution of 1987. The religious impact of Protestantism continues to dominate many national understandings and acceptance of vodou. The penalisation and processes of folkorisation of vodou are seemingly intricately associated with the advent of the Haitian school of ethnology. This demonstrates that the first investigations of the ethnographic movement we developed in the context of the prohibition of vodou which uncontestably influenced the form and content of the results. The approach adopted currently by the director Erol Josue is to place vodou high on the agenda, and has signalled towards thematic diversity, as well as methodologically and theoretically marking a new turn in Haitian ethnographic studies. His mission has been to create platforms that embraces vodou heritage as part of Haitian identity.

I felt like it was a mere glimpse, the insight I got during the month there, one that could expand into an entire vision. I fell in love with Haiti, despite difficulties I encountered and despite so many people described it as a place where they’ve truly lost hope, despite the upheavals and the insecure and violent time it was. I can’t wait to return and continue building relations and learning more about such a treasure of country, history and future.

And how could I leave without a good send off?