The most famous song about Brazil, ‘Aquarela do Brazil’, celebrates Brazil for being, tautologically, ‘Brazilian’- ‘Brasil Brasileiro‘– and it’s more than just clever (or stupid) play with words. Brazil is essentially and deeply, Brazilian, more than any other country or culture I’ve known is ‘itself’ (and I’ve been fortunate to know a few). It is happily and confidently autonomous. Its expressive cultures seem to fragment and multiply to suit new needs without worrying about dilutions of essence, without provocations of submitting to external influence.

Brazil’s leading cultural myth is ‘anthropophagy’ or cannibalism, and, indeed, Brazil cannibalises external cultures, swallows them up to suit its needs, and uses them to generate newer variations of cultural forms established as ‘Brazilian’. In the field of social dance, this makes Brazilians versatile dancers and Brazilian dance floors open to all kinds of dance and music forms. But it also means a bewildering variety and sub-forms within Brazilian social dances. This adaptability combined with inwardness is what makes Brazilian dances, just like Brazil itself, Brazilian.

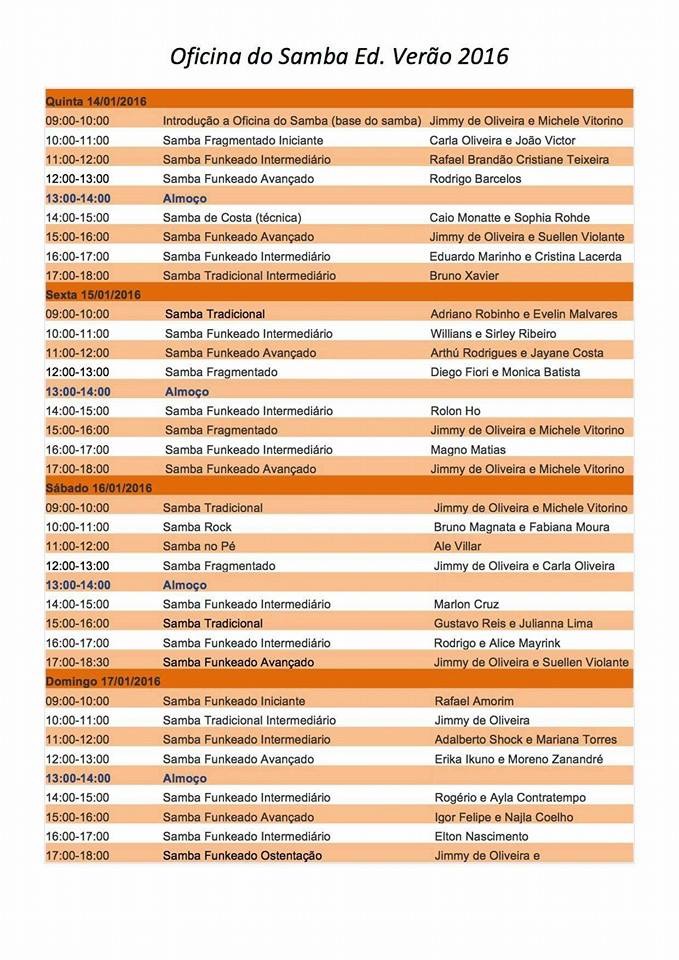

‘Aquarela do Brasil’ celebrates Brazil as land of the samba and the pandeiro but as anyone with a faint knowledge of Brazil knows, there is no one samba. In the words of Jimmy de Oliveira, founder of Rio de Janeiro’s Academia de Dança Jimmy de Oliveira, ‘many sambas, but one single passion’. At the Academia’s Oficina do Samba that I attended last week (14th-17th of January) in Rio, this reality was manifested in the timetable for the weekend’s classes, which alternated between samba tradicional, samba funkeado, samba fragmentado, and some offerings of samba rock and samba no pe thrown in.

Samba no pe, or the samba that is danced solo rather than in couple hold, is only one kind of samba, though the love that Brazilians feel for it was evident in the massive ovation that the class of samba no pe received from the workshop participants. This is the samba that is showcased in the Rio Carnival, and fittingly our teachers Ale Vilar and Kaila Mara were members of the historical samba school Mangueira. While teaching they insisted that samba is ‘alegria’ (happiness) and ‘sorriso’ (smile), so that smiling and a radiation of good energy was part of the learning process as much as the actual steps of the dance.

https://www.facebook.com/academiajimmydeoliveira/videos/1020341951337507/?theater

While samba no pe developed in the Carnival schools of samba, in the dance halls (gafieiras) of central Rio also developed samba de gafieira, or samba as a couple dance. Today we can still visit some establishments that were founded at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, such as the Centro Cultural Estudantina Musical, Rio Scenarium and the Clube dos Democratos. Here excellent live bands play and you can either join the locals singing along while doing what I call the ‘samba shuffle’—a basic movement of the feet to samba time—or show off the samba de gafieira skills that you’ve honed in a dance class at Rio, London, Buenos Aires, or indeed, the Oficina do Samba.

But samba de gafieira is only the beginning of the story. I had already encountered the curious hybrid Brazilians call ‘samba rock’ at the Exalta Afro festival that I had attended in Sao Paulo some years ago. It seemed to me then that samba rock was a dance style devised by hipster Brazilians in the 1960s to enable them to continue dancing in partner hold to rock music from the Anglophone world- music with a strong downbeat and pretty much zero interest from the perspective of rhythmic syncopation and layering. Despite the blandness of the rhythms of rock compared to the sounds of bossa nova and samba people wanted to dance to it because it was cool music; and they continue to do so.

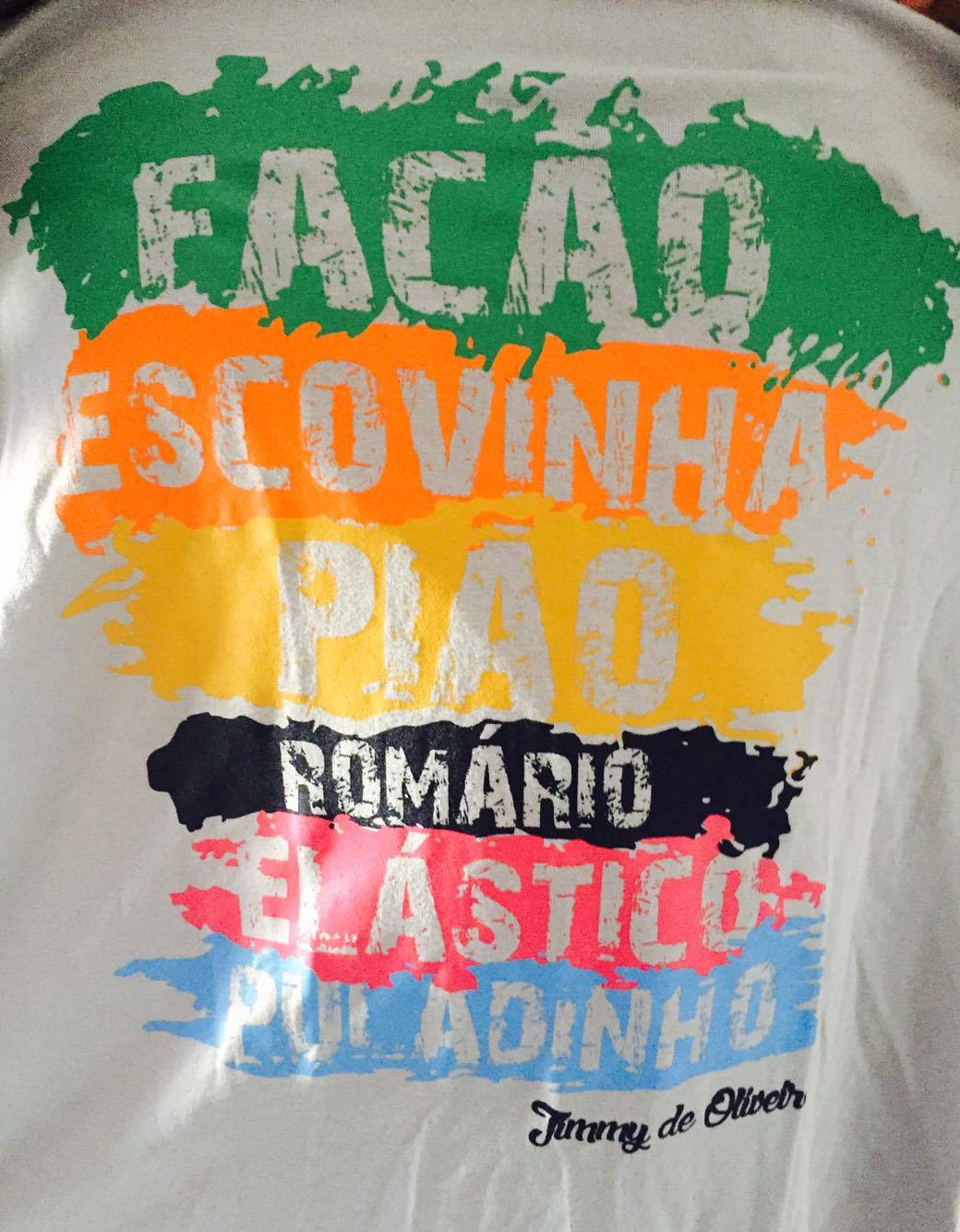

The same impulse—to adapt samba as a couple dance to new music, rather than abandon couple dance completely—has led to samba funkeado or ‘funky samba’. Its creator, Jimmy de Oliveira, said to me that it arose from his hero-worshipping of Michael Jackson, and his desire to create samba styles that could respond to ‘funky’ and ‘groovy’ music. Samba funkeado allows the dancer to syncopate and exaggerate the codified steps of samba de gafieira. As the samba de gafieira rhythms are already syncopated to begin with, this exercise in re-syncopation breaks through normalisation of the rhythm by creating new, surprising, and playful ways of keeping the relationship between dance, music, and dancer fresh.

It is also a way to keep the conversation going between Brazil and the USA as two major inheritors of the Black Atlantic. Thus samba funkeado responded initially to North American music seen as ‘funky’, rather than the Carioca funk and other forms of Brazilian funky music. If we accept these principles as intrinsic to the way Brazilians feel about samba, then ‘samba fragmentado’, the latest form of samba de gafieira that Jimmy has created, is a logical development. Here, samba steps are deconstructed into successive poses that are held for a micro-second—or longer—depending on the call of syncopation. The appropriate music is hiphop or R n’ B, or Brazilian music created in that mould.

When asked about the difference between samba funkeado and samba fragmentado, Jimmy and his team responded not in words but by demonstrating to me the different feel of each style. But as an Australian participant in the Oficina helpfully articulated to me, samba funkeado is ‘photo-finish’; samba fragmentado is ‘time lapse’. In both cases there is a playing with and stretching out of and collapsing of time. We as dancers experiment with and experience time and counting in a multiplicity of possibilities, exploding the unevenness of syncopation when it has become absorbed into the framework of the dancer’s expectations.

Yet while all this teaching of funkeado and fragmentado is going on, there is also due respect being paid to ‘samba tradicional’ (traditional samba)- which is what samba de gafieira is called now to distinguish it from the newer styles. This re-labelling is as necessary as is the retention of the style for dance pedagogy: the newer styles do not abandon the 56 steps of the samba de gafieira repertoire (would be interesting research to unearth when and how this codification took place) but play with them and develop them to suit different musical demands and moods. I asked Jimmy de Oliviera whether the funkeado and fragmentado styles represent an evolution of the dance style in response to new and non-Brazilian music, and he enthusiastically agreed: ‘Isso!’

This acceptance of ‘evolution’ in dance is in sharp contrast to the debates around kizomba’s evolution into urban and so-called traditional styles, and indeed the stiff resistance by many to the label of ‘traditional’ for kizomba styles that had developed initially in Angola. It seems to me that the difference lies in a sense of collective security that surrounds a dance that is accepted universally as national heritage and indeed whose strong status within the nation is matched by weak transnational presence—unlike kizomba, which has transnationalised spectacularly over the past decade and whose newer styles are being developed amongst Afro-diasporic communities in different European locations, most strikingly, France.

Practitioner of the Haitian dance style kompa Cliford Jasmin has pointed out that a strong dance identity for a genre is not necessarily matched by a strong music identity for the same genre. While this realisation can help us understand some of the debates around kizomba, I feel that what has let samba fragment and multiply without any depletion in the symbolic charge of samba is the co-existence of a strong music and dance identity for it, as well as the Brazilian tendency to cultural cannibalism and autonomy which has kept samba happily and comfortably Brazilian. This additional dimension would explain the differences between the global fates of samba de gafieira and another Afro-diasporic genre which exhibits an equally strong dance and music identity— salsa.

In the end, all Afro-diasporic social dance is about evolution, resistance, adaptation, subterfuge, and swag. These were the conditions under which samba de gafiera was forged out of the maxixe, the earliest urban Brazilian couple dance, which itself emerged from the dialogue between African dances of the Plantation such as jongo and lundu, that freed slaves from Bahia brought south to Rio, and European couple dances such as the waltz, the polka, and the mazurka. The maxixe, Jimmy de Oliveira explained to me, was a dance of humour, caricature, and exaggeration, and indeed, while dancing it with him, I was strongly reminded of images and old footage of the Cakewalk, that dance of the North American plantation, which mocked the masters through exaggerated homage to their elegant couple dances and balls.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dIj9dq-nKew

The couple dance, formed in equal parts through resistance, mimicry, sly civility, and play, a dance of desire between the forbidden and the seized, the master and the slave, is, in my opinion, a foundational scenario of the Americas. It is a mythical moment of the birth of a culture through the process of creolisation. Its survival and adaptation in Brazil through the continuing evolution of samba de gafieira is one of the ways in which we can understand both how Brazil can both be intensely Brazilian and intensely part of the wider world of the Black Atlantic African diasporas. Watch here a video we took of a moving choreographic sequence by two dancers in Brazil which enacts the meta-narrative of movement from the African dances brought to the New World by slaves to couple dances such as samba de gafieira.

https://www.facebook.com/minkyoung.mk.kim/videos/10205454809390359/?theater

With thanks to: Minkyoung Kim, my Research Assistant in Brazil and dancer extraordinaire; Jimmy de Oliveira and his entire dance team; Flavia Amiral; Anderson Mendes de Rocha, my first teacher of Samba de gafieira; Arthur and Aiste, my gafieira teachers in London, and a special ‘obrigada’ to Arthur for introducing me to Jimmy in Rio de Janeiro.

All photos are by Ananya Kabir; except where otherwise acknowledged!