Drawing on three conferences I attended during the past few months in Bordeaux, Sussex and Nice, this brief glimpse of the realities and contexts of academic life seeks to offer a broad overview of how and in which extent music and dance topics are addressed within African studies conferences these days.

The 3rd Meeting of African Studies in France took place in Bordeaux at Sciences-Po from June 30 to July 3. This edition was entitled L’Afrique des/en réseaux and I participated in a panel organised by Denis-Constant Martin (LAM/FNSP/Sciences Po Bordeaux) which was placed under the theme “Circulations et créations : musiques et danses en Afrique et dans l’émigration” (“Circulation and creation: music and dance in Africa and emigration”). Thus I gave a paper exploring lines of enquiry of my new research agenda within Modern Moves: “La musique cubaine en Afrique: la création d’une “musique africaine moderne” aux Indépendances” (“Cuban music in Africa: the creation of a ‘modern African music’ at Independence”). With this conference, I amazingly moved between England and a French town that has been historically under English rule at a certain point. Bordeaux was indeed a territory belonging to the English crown during the Middle Ages and had later played an important role within the Atlantic trade. But well, this is another story!

The British counterpart of the French Africanist meeting was the Biennal Conference of the African Studies Association of the UK held at the University of Sussex from September 9 to 11. There, I was involved in a panel entitled “Dance, Socio Cultural Change, and Identity politics in African History” curated by Cécile Feza Bushidi (SOAS). The paper I presented, “Dance as Historical Narrative: The National Ballet of Mali”, addressed the political issues revealed by the reconstruction through dance of a pre-colonial historical narrative, which played an important part in the nation-building process of newly independent Mali in 1960.

Finally, I’ve just returned from another international conference held in Nice at Sophia-Antipolis University from September 26 to 27. In a smaller frame than these previous huge conferences, the original attempt of this one was to compare the notion of “contemporaneity” through music and dance in Africa and South Asia (La “contemporanéité” dans les pratiques scéniques en danse et en musique : regards croisés entre l’Afrique et l’Asie du Sud). Drawing on my work in Mali, I presented a paper entitled “Investir le “contemporain”: Regard sur les troupes de Ballet au Mali” (“Investing the “contemporary”: A look at the Ballet companies in Mali”).

In the first place, while looking broadly at the programmes of these three conferences (Bordeaux, ASAUK, Nice), notwithstanding their respective size, we can observe the efforts made to create a space for live artistic performances as part of the organisation: music concerts, dance performances, movie screenings are now definitely part of these intellectual events.

However, in the frame of the two bigger Africanist conferences, this emphasis on cultural productions is not completely reflected within the huge offer of panels. Indeed, in spite of the presence of prestigious keynote speakers and several hundreds of researchers from all over the world gathered in more than fifty panels in Bordeaux and more than 150 in Sussex evolving in parallel — this accumulation is really a challenge because you are always interested in three or four panels (if no more) obviously scheduled at the same time! — papers addressing the topics of culture and arts represent a very minor part, and within them, the ones about music and dance are even more marginal.

Secondly, of course because of the postcolonial networks, Francophone and English-speaking African countries are much more represented than the Portuguese-speaking ones, therefore the research being carried out by some members of the Modern Moves team is particularly important to offer a kind of compensation to this postcolonial state of affairs. Yes, I have to admit that, after coming back from this massive Africanist conferences, I am even prouder of the work undertaken by Modern Moves project which indeed intends not only to go beyond the disciplinary borders but also enlighten some cultural aspects which are definitely marginalised within African Studies, and even more, within Anthropological perspectives.

Finally, as the smaller size of the third conference I attended allowed me to be more focused on the development of the questions raised throughout the two days of debates, I am happy to share here some conclusions that emerged from them.

The blurb of the conference emphasized an interrogation of the notion of contemporaneity, which appears quite strongly in the field of “traditional” music and dance in Africa and South Asia since 1980s. The papers presented thus addressed these topics in different ways, either from an academic or artistic perspective, or even both sometimes! Consequently, and as I presented myself regarding the Malian artists I worked with, we can assess how multiple are the interpretations of this notion of contemporaneity, even if some similarities in the ways this notion is used among African or Indian artists were interestingly revealed at the same time. This notion is also part of an artistic process: how do these artists “become” or “make” contemporary? How do they liaise in their work the aesthetic codes they have to deal with (either from “traditional” or “contemporary” dance styles for instance)?

The question of being artistically contemporary is also an economic matter as many international cultural funders are promoting it. As different examples showcased, the way of some traditional forms tend to be mixed with others foreign influences in a process conceived as contemporary by the artists or the promoters, we can wonder whether the contemporaneity of “traditional” music dance practices either from Africa or South Asia is really and only marked by this process of fusion, hybridity, mixing (or whatever word) through the myth of the intercultural encounter, hugely promoted within World music and “ethnic dance” festivals, recordings and networks.

As far as I am concerned, I am convinced that there are also some local resources of modernity or contemporaneity that are used to renew and recreate a repertoire, traditional or not. However, we could perceive in some comments or questions raised by the public that this notion of the contemporary is still conceived as an hegemonic notion coming from the West, exactly as modernity was. It seems that the dichotomy between tradition and modernity is still resilient: even though many works have already deconstructed this “perverse couple” (Jean COPANS 1990: 85), there is always more to do about it!

ELINA DJEBBARI

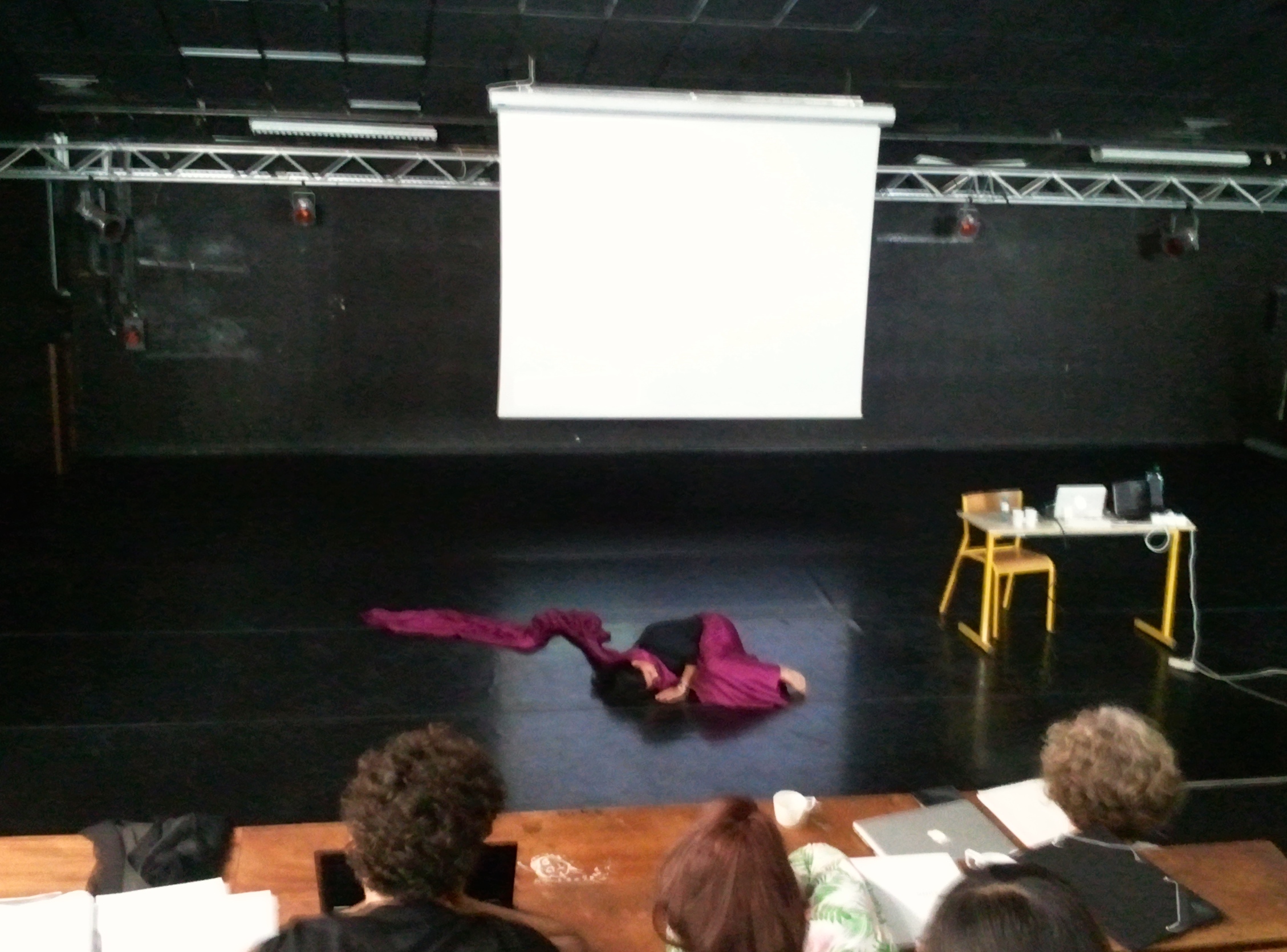

Featured image: Keynote lecture in Bordeaux. Photo courtesy Elina Djebbari.