Over the past few months I have been busy with all sorts and kinds of research, from attending vogue balls in Paris and Berlin to going on a special research visit to the Katherine Dunham Archives held at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois — a place not too far from East Saint Louis, Illinois, where black performance talent like Katherine Dunham, Josephine Baker and Tina Turner once held court.

For anyone interested in Katherine Dunham the archive presents a real treat: you’ll find materials ranging from original scores to Dunham’s own passport, and from costume drawings to Western Union telegrams (!). In addition, when leaving the archive I was told that 100 more boxes had just arrived, a research delight!

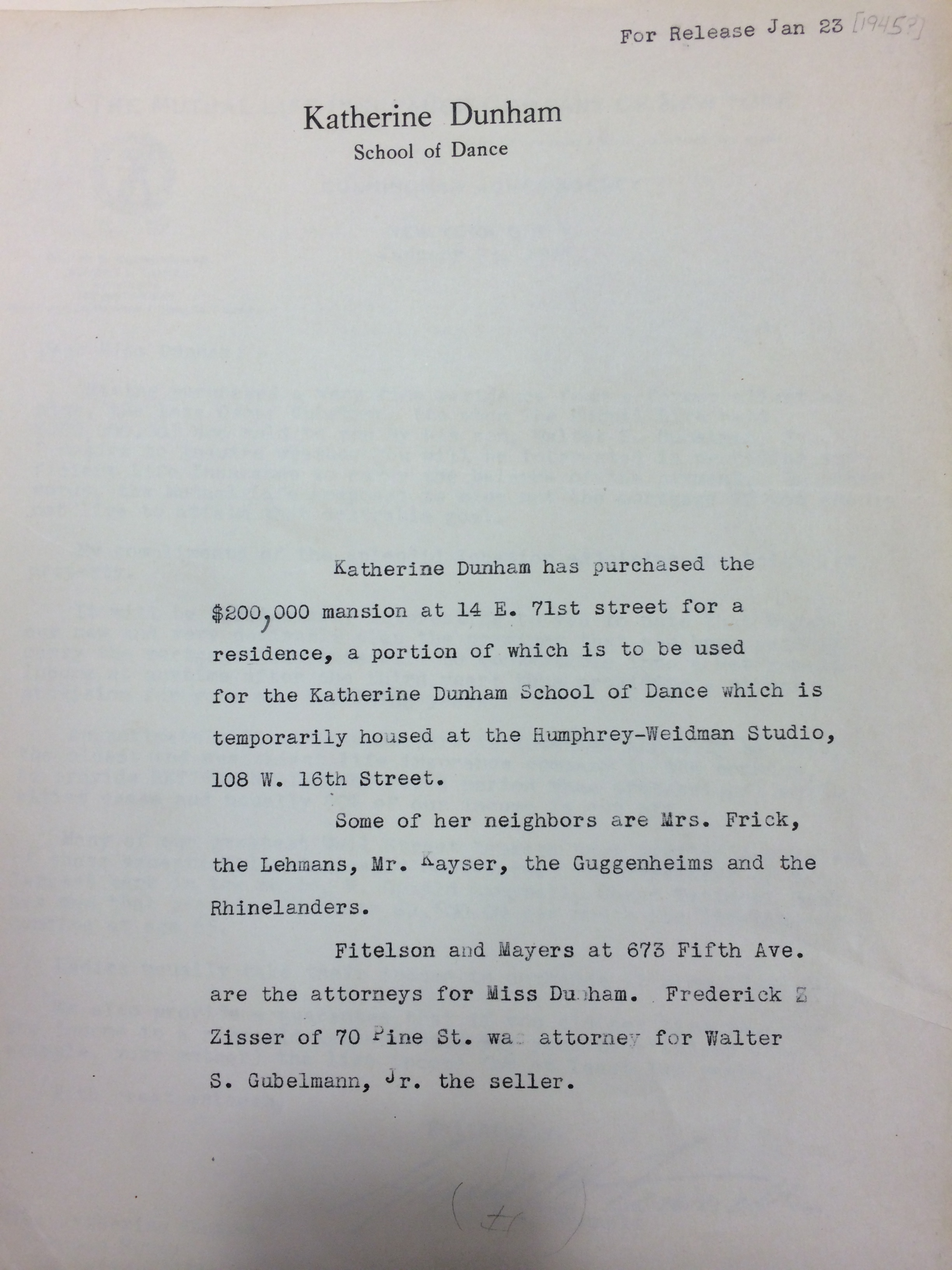

One of the most memorable things I found in the archive was a 1945 New York Times article about how Katherine Dunham had purchased a $200,000 house at 14 East 71st Street on the Upper East Side, an extremely wealthy area of New York City, to live in and to act as a headquarters for her school. This was big news given that her neighbors were the Fricks, the Lehmans and the Guggenheims, as stated in the press release, which Dunham used to drop the news.

The interesting thing about the article was that the tone was very much about how a black woman was able to purchase such an expensive home, particularly during a time in the US when African Americans still did not have property rights and indeed could not purchase their own homes in certain areas (and would not be able to for at least another 20 more years). Of course, the article never spelled any of this out directly, but the date it was published along with the fact that the paper talked to Dunham’s neighbors to get their take on what they felt about having an unknown black woman buy such an expensive house lets us infer the punch line of the article. “I’ve never heard of her,” one neighbor commented — the shade of it all. Indeed, the house was actually not purchased by Dunham herself but by lawyers, which drives this point home even further.

When I tell you that the archive holds deep financial records of Dunham’s company it sounds pretty boring, I’m sure. But these financial secrets tell a colorful story of their own about the labor that goes into making a performance happen. You’ll find box office statements showing how well a performance did in a given place, contracts stipulating what rights Katherine Dunham has and what rights the hosting venue does not have – for instance changing the performance at the last minute was not an option. There were even details on how much a single performance cost. We even know how much her dancers made. For a February 11th performance in 1944 at the Shubert Theater in New Haven, Connecticut, just a stone’s throw away from Yale University, Dale Wasserman, the highest paid dancer for that show, made $125.00. Ora Leak, one of the lowest paid, earned $45.00.

But it’s not just all ledgers and receipts. Fans sent letters professor their love and the great black American opera singer Marian Anderson wrote her a letter requesting a donation for charity. Some of the juicy stuff — the real tea — included letters from fans who were desperate to be a part of the Company as well as audition headshots from prospective dancers that included their professional resume at the back. On July 25, 1955 Miss Mary Irene Wemberly of Chicago auditioned for the Company. Her “Chief Ambition,” as it said on her resume, was to “become a member of The Katherine Dunham Dance Group.”

Something tells me that Dunham was a bit of a diva, not unlike most celebrities of her stature – and she was a celebrity. On November 15th, Dorothy Gray, an assistant to Katherine Dunham, informed the Locust Theater in Philadelphia that their choice of hotel would simply not do. “In Philadelphia Miss Dunham does not want to stay at Walton Hotel,” the Telegram read. “I suggest Bellevue Stratford-Ritz.” Built by George C. Boldt, the name behind the famous Waldorf-Astoria luxury hotel in New York, the Bellevue Stratford-Ritz was a luxury hotel built at the turn of the century that was meant to compete with its New York counterpart. For me, this really solidified that Dunham absolutely penetrated the laps of luxury, which during this period was almost certainly a majority white world (pre-desegregation).

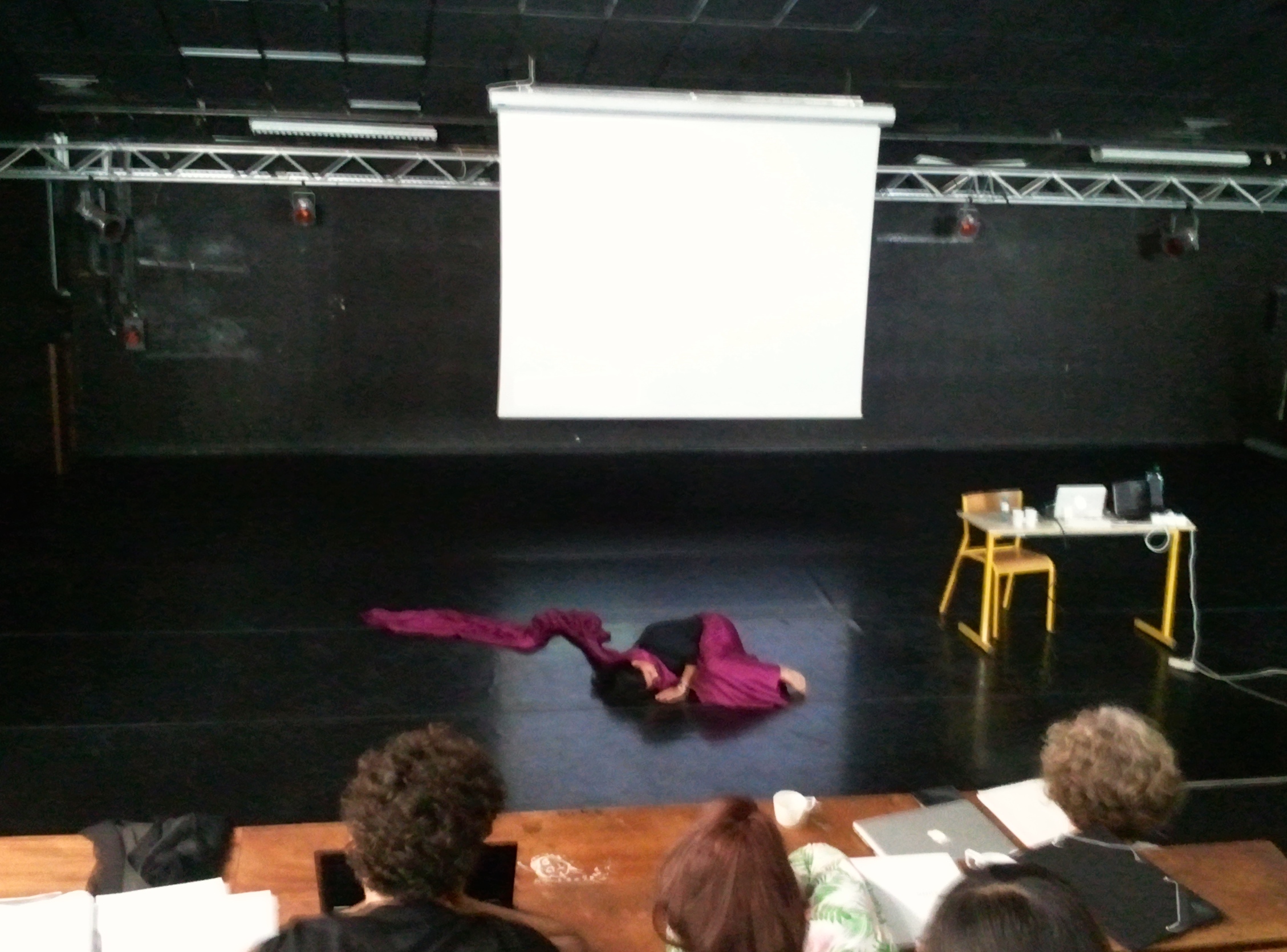

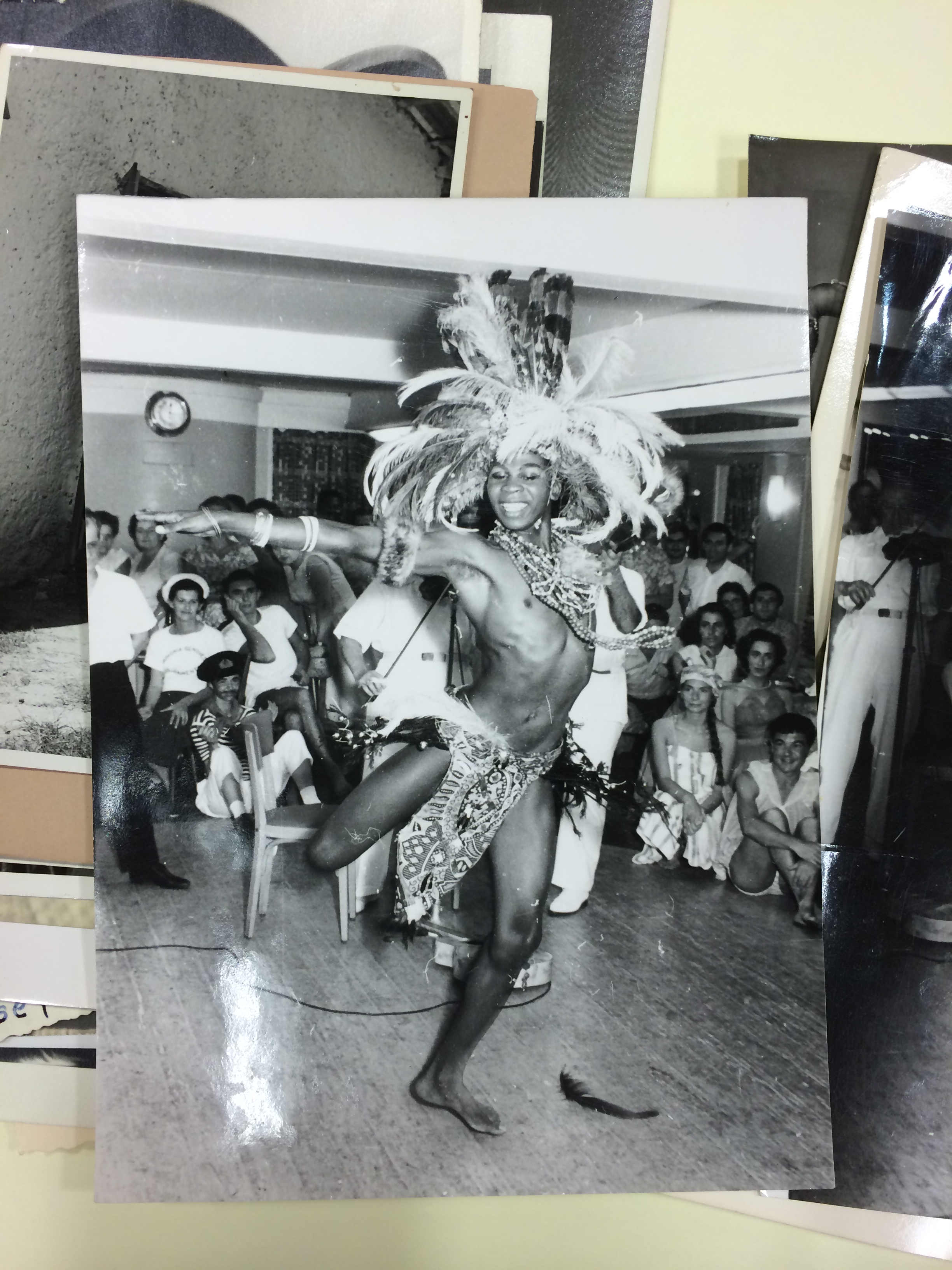

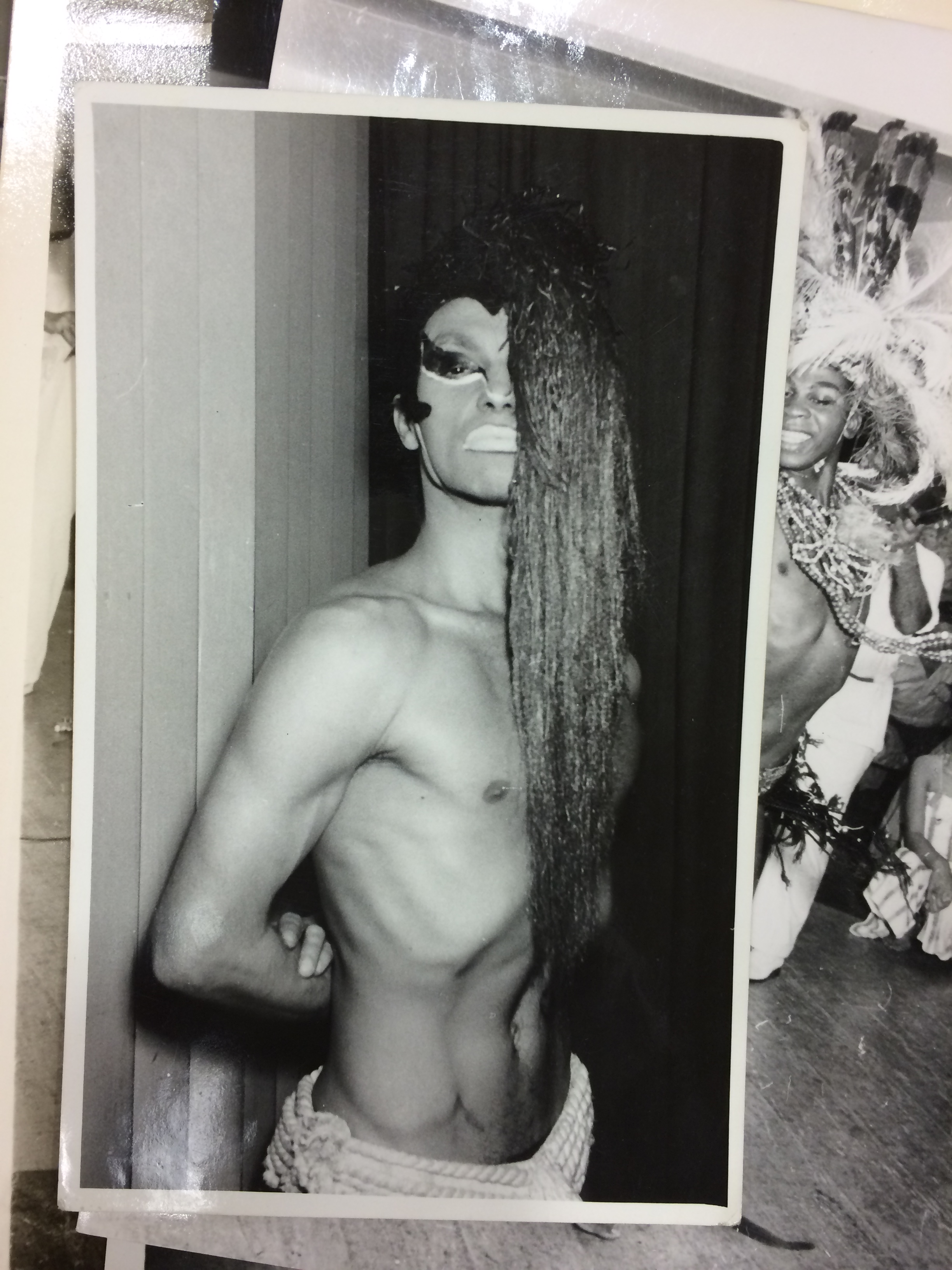

In my work I am always on the hunt for queerness, as I am interested in how people make space for themselves outside of a dominant hetero-patriarchal gender binary. I knew that there had to be some type of queerness when looking through Dunham’s archive, and I was pleased to find at least two images that satisfied my thirst. One of them shows a dancer in what must be a carnival or Mardi Gras costume, a beaded headdress, drum beating, and you can tell he is moving a great deal because one of his feathers has fallen on the floor from his headpiece.

The Caribbean has a great history of homophobia, but it always seems like Mardi Gras and carnival are two events that are malleable in the way those types of parties allows participants to break out of the normative roles of the everyday. This would, of course, tap right into Mikhail Bahktin’s theory of the carnival as providing just that type of experience.

The other queer image is a totally static one, meaning there is no movement. It shows a male performer in a type of drag. His face is painted, the lips white and the line of the eyes stretched out and up, and he wears a long half wig with a cropped headpiece on top. I liked this image because, in 1944, we see that there were specific types of queerness that were possible through performance.

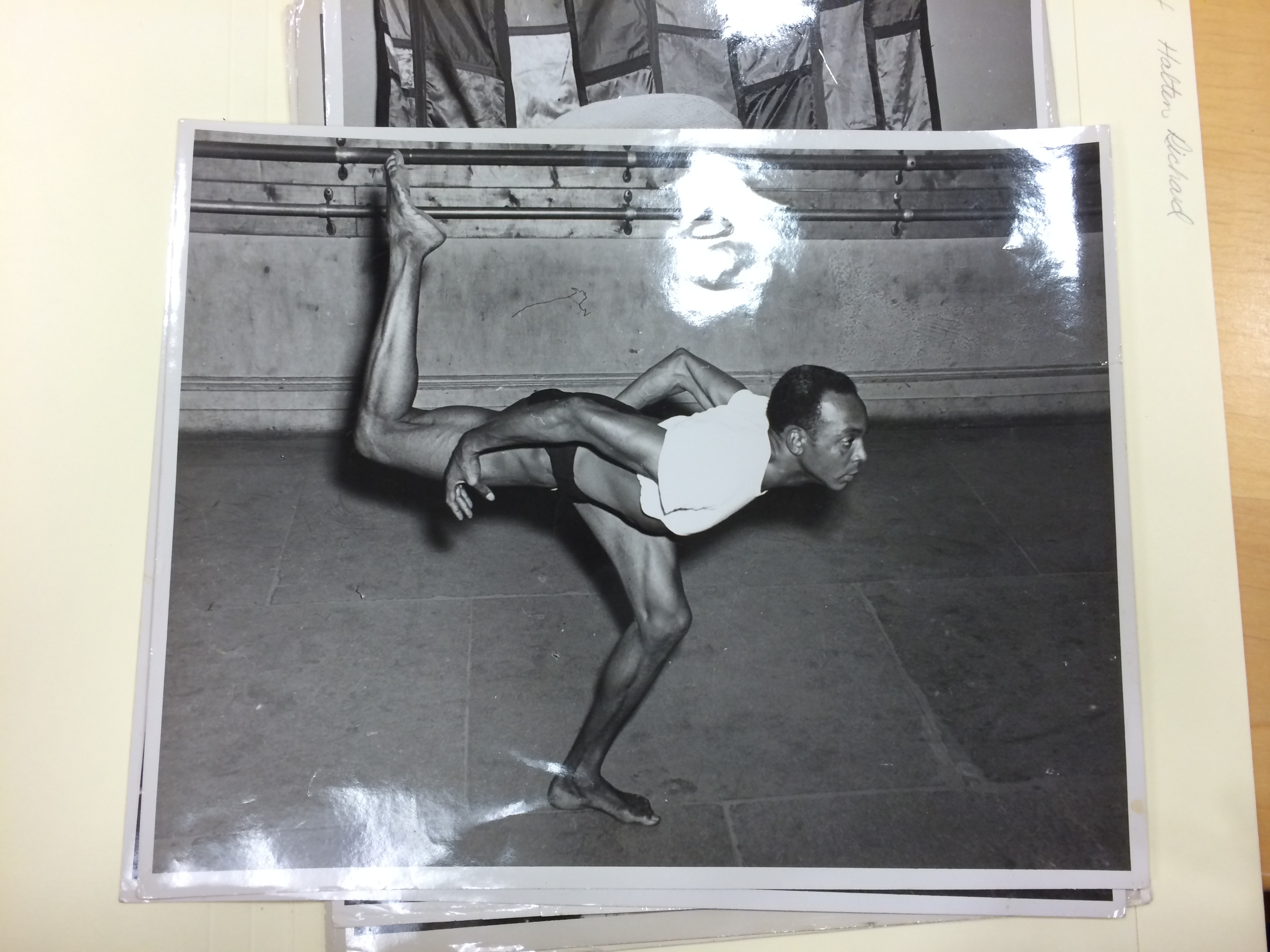

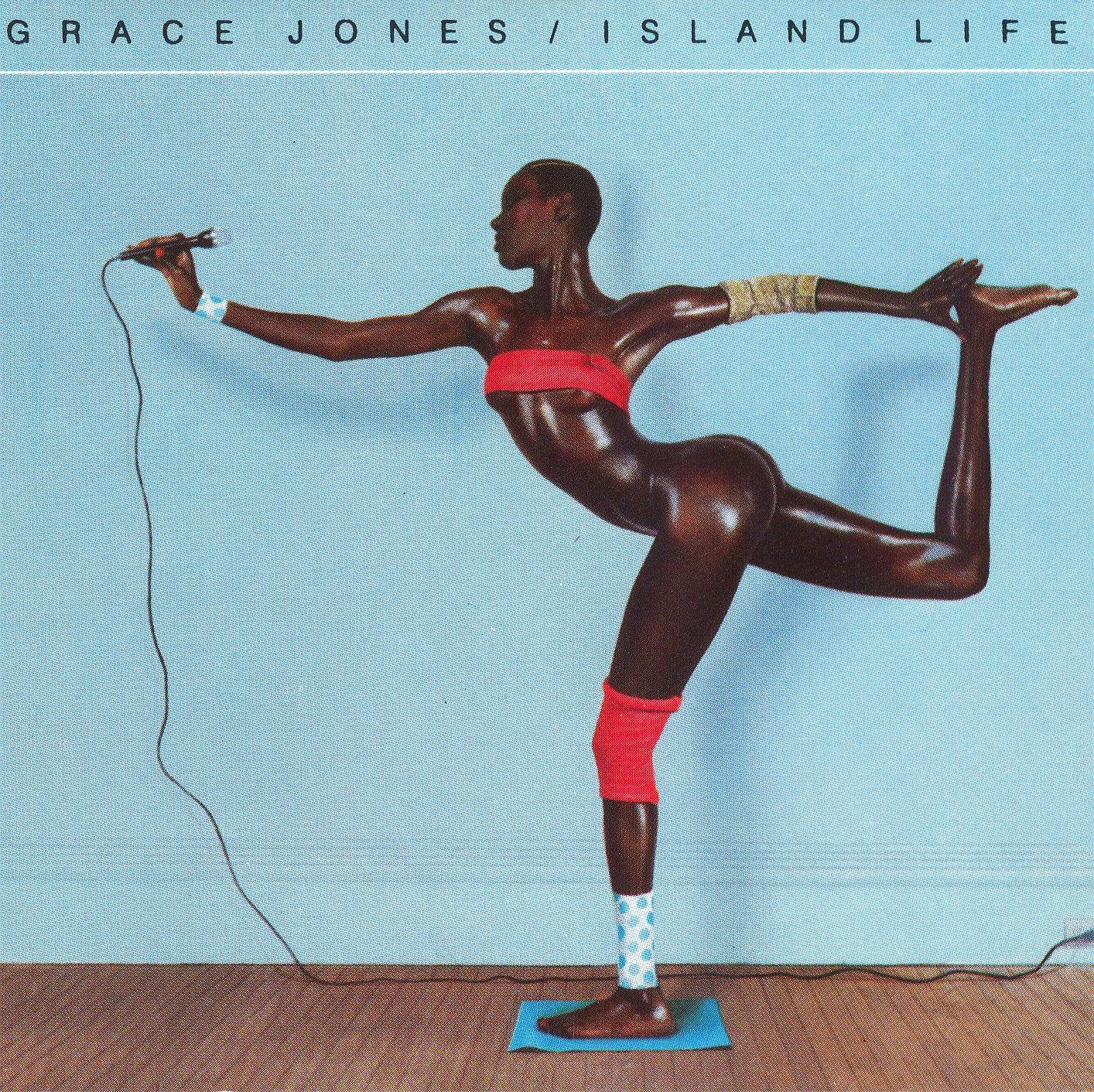

The last connection I noticed, one that is extremely powerful in bridging the gap between the legacies of Katherine Dunham’s dance and the movement of pop culture is an image of two dancers. One of them is shiny, very shiny, as he stands there in an athletic pose. There is already some The image shows a male dancer, relatively sweat-covered, holding a stretched out pose in a dance studio. The leg is curled back and up in the shape of an “L,” the arms cocked back as if attached to springs.

Taken together, these two images appear to be inspiration for, or at the very least diasporically connected to, Grace Jones’ 1985 album Island Life. In that famous image, shot by Jean-Paul Goude, Jones’ shiny Caribbean body poses in a similar fashion: leg curled up and back in the shape of an “L,” arms stretched out. While the poses might not be exactly the same, they do appear to come from a similar movement archive and indeed the sheen that appears across both images is an unmistakable trope of blackness.

MADISON MOORE