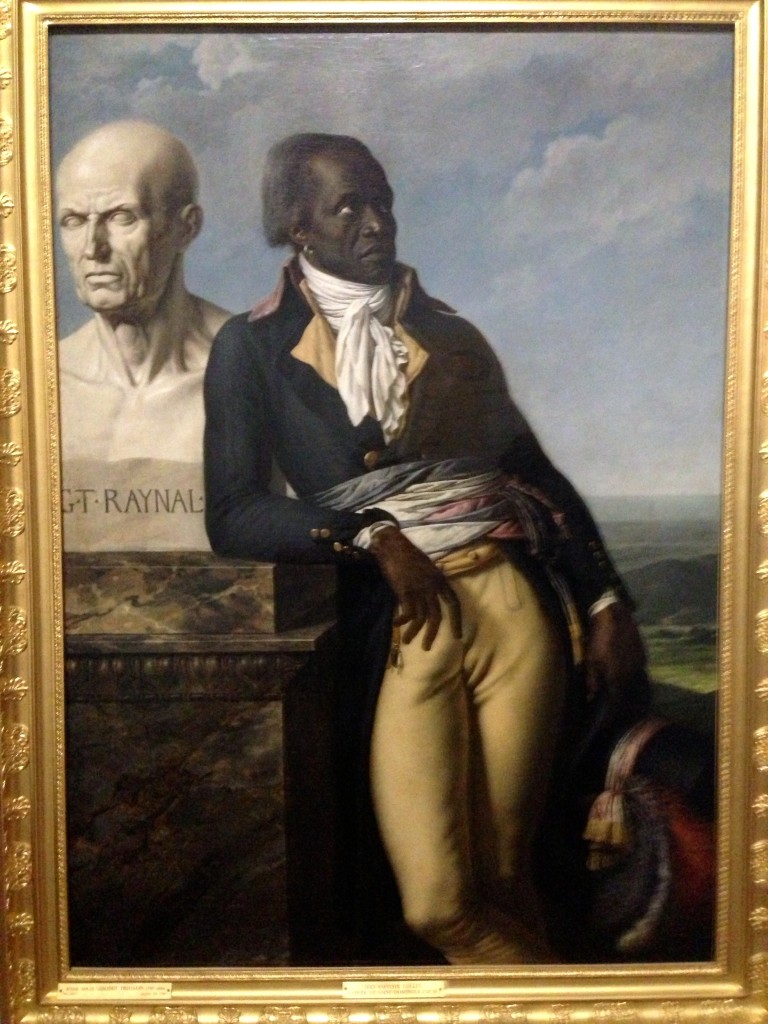

At the European University Institute in Florence in 2012, I had asked the Vasco da Gama Professor of History Jorge Flores about research on the movements of people from India through the Portuguese-speaking world. After all, the Portuguese Empire had stretched from the East Indies to Brazil and Vasco da Gama himself had been the first European to round the Cape of Good Hope to touch the shores of Western India. And when people move, their music and rhythms move with them: was there any evidence of rhythmic travels between India and Africa through the Portuguese imperial web? Well, the short answer from the expert was— of course people had moved. The archives had enough evidence for these movements especially of civil servants, school teachers, and other such bureaucratic personnel. But in 2012 it seemed that no one had done much research on this topic yet. And as for their music— well, that concern was not even on the general research radar.

That was over two years ago and all sorts of work on this transoceanic world is now in progress. The work of Pamila Gupta and the Facebook group Indo-Portuguese History are only two such examples. But we’re waiting for work on the musical and kinetic connections between the Indian Ocean and Atlantic Ocean routes shaped by different European empires– especially the Portuguese imperial world, whose fast caravel ships that had first opened up those routes as early as the sixteenth century. In Anglophone scholarship, in the meanwhile, there seemed nowhere to start, no prior historiographic or ethnomusicological exploration to base my own investigations on.

What has been studied is the music that evolved as the Portuguese moved across the Atlantic Ocean, transporting African slaves from one side of the ocean to another, with transit points in Lisbon, Cape Verde, and even islands in the Caribbean belonging to other powers, such as the Dutch-controlled Curacao. As elsewhere in the Black Atlantic world, the horrific act of human trafficking has left, paradoxically, a rich legacy of music and dance forged through the forced displacement and interaction of peoples to feed the machines of capitalism and empire. From trauma and physical suffering emerged a paradoxical exhilaration of the body that moves to enjoy itself in a social space.

For some reason, the Portuguese empire’s musical legacy is particularly sweet, haunting and rich. We just have to listen to music from Cape Verde, often considered the first creole society in the world, to get this fact. But not just Cape Verde: Brazil and Angola, too, have given us the finest music of the Black Atlantic world. Depending on the trends in ‘world music’ marketing, some of these musical traditions and their representatives are better known globally than others: Cesaria Evora from Cape Verde and Brazilian Bossa Nova come to mind. The rest is the work of aficionados to discover or indigenes to appreciate.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ltIRbnYw3Qg

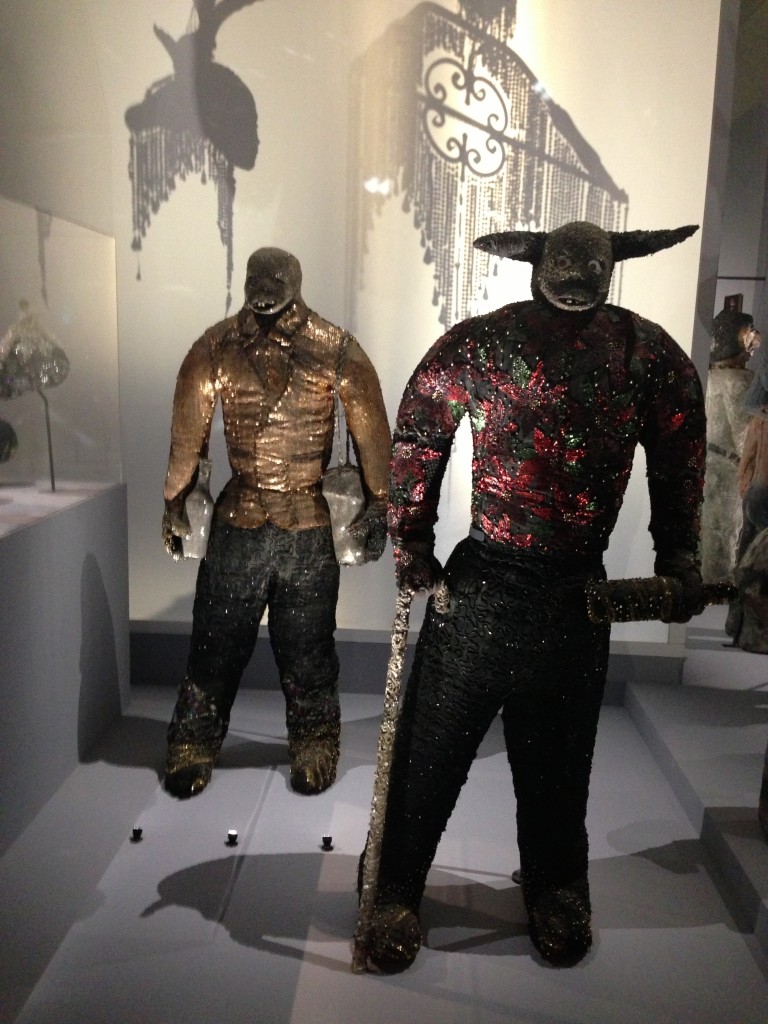

As for the dances associated with these traditions, they call for another level of discovery, enjoyment and analysis altogether. ‘World dance’ cannot be marketed in the same way as ‘world music’. One cannot be an armchair enthusiast of dance, cultivating a rarefied appreciation of unusual music in the solitary comfort zone of one’s armchair with the help of a music system or fancy headphones. Understanding dance requires contact with other bodies, dance floors, and the willingness to share your sweat with random strangers—both exhilarating and not to everyone’s taste (sadly).

Nevertheless, there is a lot of scholarship on salsa (both the music and dance), which is now an unambiguously globalised leisure form. Salsa developed through the intermingling of rhythms, body movements and musical instruments from Africa and Europe within the Spanish-speaking Americas, and it is now danced socially almost everywhere in the world. During the last six or seven years, couple dances from Angola, namely kizomba and semba, have infiltrated the transnational spaces where salsa reigns, particularly in France, Eastern and Central Europe and the UK. This transformation of a salsa-ruled dance floor by social dance from Portuguese-speaking Africa became part of my research agenda.

However, to focus on the Atlantic side of music and dance from the Portuguese-speaking world is only half the story. Geography and history both create these webs of cultural contact and transmission, particularly for those processes that were set in place when human beings still moved around in ships rather than aeroplanes. The southern half of Africa narrows to where two oceans meet, and the Portuguese (ex)colonies of Angola and Mozambique, one facing the Atlantic Ocean and the other, the Indian, are not so far flung as eastern and western African coasts further up on the continent. Not only that— Mozambique has been part of an Indian Ocean world of trade and cultural contact long before the Europeans came to Africa. Indians, Arabs, Africans and Malays moved around this world, sharing commodities, languages, religions, and knowledge of seasonal winds (the ‘monsoons’). Do the histories of these oceans meet as do their waters?

Cosmopolitan maritime communities were formed in the pre-colonial Indian Ocean that seem mythical to our narrow present-day vision, which is shaped by assumptions of cultural clash, monolingualism, and a tendency to put ‘third-world peoples’ in compartments dictated by the selective ghosts of empires past. By this logic, Indians are to be found mostly either in India or in the ex-mothership, the United Kingdom, and Africans, either in their respective African countries or whichever ex-mothership their country was colonised by. As an aside, I don’t think academics yet have a way to understand a cultural phenomenon like Dubai, though everyone understands its economic basis. There were other (nicer) versions of Dubai in the past, whose remnants still survive in the present—for instance, the Ilha de Moçambique, where Vasco da Gama stopped to take a breath before moving on to India.

On the Ilha Vasco da Gama found Gujarati-speaking peoples from the Western coast of India, as well as Arab and African peoples speaking a multitude of languages and practising a multitude of religions. This is the polyglot world which is depicted with nostalgia by novelists such as Amitav Ghosh and M. G. Vassanji, a world which was overtaken by the capitalist forces driving European expansionism. But these empires presented new and different opportunities for the movement of peoples and cultures which sometimes layered themselves on older histories and processes. It is easy to forget this fact, because the temporalities of Empire are so powerful in our imaginations. In chasing the movement of people between Goa and Mozambique during the Portuguese Empire, I gradually realised that before and after the fact of Portuguese Goa, there were Gujaratis moving between Western India and Eastern Africa. Many of these were from Gujarat’s multiple Muslim traditions—Khojas or Ismailis, Bohras, Twelver Shias, and Sunnis.

When you start looking for something, suddenly evidence for it pops up everywhere. But research also depends on serendipitous connections, things that you find when you are looking least hard. My friend Samira Sheikh has been researching medieval Gujarat for many years now and thanks to her I know something about these sea-faring, African Gujarati communities. But I already ‘knew’ about these communities anyway. Other Indian friends of many years, themselves of Gujarati Muslim families, have family members living in different Indian Ocean facing African countries. So why did it seem so exotic and exciting to me to discover that a very Ismaili-sounding ‘Zahir Assanali’, originally from Mozambique and now living in Cascais, Portugal, is the director of one of the biggest musical operations in the Portuguese-speaking world?

Maybe because we don’t always bring together the things we know from life to the things we know from research. Maybe because academic research is often conducted in narrow segments and, in our quest to know more and more, we go deeper and deeper rather than cast our nets wide. We need to long for a bigger picture to start joining the dots. I have been a maverick researcher, moving from one area to another. Nothing should surprise me. But even so, I started when my eyes fell upon that name,’Zahir Assanali’, and the explanation, ‘a Mozambican of Indian heritage’, who organises massive concerts of Angolan music stars in Portugal, Brazil and Mozambique. I was reading an article about the current mania for Angolan music in Portugal. It was published in Portugal’s popular newspaper supplement, ‘Revista Semanal’ and had been sourced by my Portuguese teacher Sofia Martinho. I wasn’t expecting to come across a South Asian Muslim name there.

Because Zahir Assanali is the director of Grupo Chiado, one of the biggest music promotion enterprises in the Portuguese-speaking world, tracking him down was relatively easy. In a pincer-grip motion I mobilised Facebook, email and telephone to explain to him why I was interested in his work and his background. Here was my missing link between Indian and Atlantic Ocean histories, a person whose biography and interests represents the point of convergence between peoples, oceans, musical traditions, imperial and postcolonial times. Bringing Angolan music stars to Portugal and Brazil, taking Julio Iglesias to Luanda and now UB40 to Maputo, he seemed to be the kind of human ‘Cape of Good Hope’ that I was searching for in Afro-diasporic rhythm cultures. (Of course I didn’t say all that to Zahir in seeking an appointment; he might have considered me slightly crazy).

I finally met Zahir in the summer of 2013 on the eve of the ten-day Festas do Mar at Cascais, an hour’s journey from Lisbon, which Grupo Chiado was organising on behalf of the municipality of Cascais. The stage was being set up and he was in the midst of last-minute organisation. I brought along a fellow enthusiast for Afro-diasporic dance, Francesca Negro, one of those multilingual people that are quite normal in the dance world. Zahir had with him his friend and business associate, Miguel Angelo, another really important Portuguese music promoter, CEO of Soundsgood, which works with big Brazilian names like Ivete Sangalo. I was in some sort of music impresario hall of fame. In a mixture of Portuguese and English we spoke for over an hour as if we were all old friends. Zahir’s teenaged daughter dropped by. With her nut-brown limbs and wavy black locks she looked like an Indian Ocean mermaid. Behind us, the Atlantic waters brushed up against the Cascais sand.

I learnt that Zahir’s languages were Portuguese and Gujarati. I tried out my few words of Gujarati on him to our collective amusement. He told me that his wife spoke the African languages of the area of the Ilha and took seriously my rejoinder that perhaps Gujarati should also be considered an African language. When we spoke of Ismaili Islam, Miguel Angelo’s knowledge about his old friend’s religious affiliations was extended further though an impromptu discussion about different varieties of Islam—not ‘castas’ we said, using that old, old word that the Portuguese introduced to South Asia— rather, these were different ‘doctrinas’. We spoke about how it was, growing up on the Ilha de Moçambique, listening to Indian music, African music and simply, ‘music’—the kind of music that anyone growing up anywhere urban in the 1980s would have heard—Wham, Sabrina, Michael Jackson.

This international ‘music’ was what Zahir got hooked on to while working for his uncle’s record shop as a teenager and what determined his future career. Now that ‘black music’, as Miguel called it, was so popular in Portugal, it made business sense to promote it. We are in the music business for the business, he insisted. What kind of music do they listen to? Miguel said that he didn’t personally dance to ‘black music’—he liked rock, jazz, blues, bossa nova, house…. ‘but all that is also African music deep down!’ I insisted. ‘Yes, I guess so, but still’— we then went on to talk of Buraka Som Sistema, one of the best-known products of the Angolan diaspora in Portugal. ‘That is music with a European groove and an African beat’, he said. We spoke of Carnival in Brazil, the trios, the blocos, the madness. We spoke of white people in Portugal of ‘our generation’ evolving in the past twenty years towards a more inclusive musical taste, more representative of Portugal’s long connections with Africa. ‘This is a good thing’, we all agreed.

But in one of Lisbon’s long-established clubs for African music, B.Leza, I have seen older white couples dance smoothly to the sweetest Capoverdian live music. Was not in that generation’s desire to dance to those rhythms some other motivation— a nostalgia that was surely different from whatever was motivating younger consumers of Angolan music and dance today? And how could one explain the massive popularity of kizomba, semba and kuduro as social dances across Europe? This development was news to the music men, who were amazed to hear of French youth of African heritage dancing kizomba and semba every weeknight in football clubs of Parisian suburbs, kizomba festivals in Eastern Europe, and the like. Did they dance? No, Zahir said, he felt ‘embarrassed’ dancing, even though everyone else in his family danced without any self-consciousness. What did people dance to in Mozambique? I asked. ‘Everything, kizomba, marrabenta (a Mozambican music), zouk.’ ‘Salsa?’ ‘No, not really.’ As he joked, ‘Salsa doesn’t work here. We leave that to the Spanish(-speaking) people’.

The transoceanic Afro-diasporic world is shaped by unexpected alliances amongst language groups. Thus zouk from the French-speaking Antilles is everywhere in the Portuguese-speaking world, but not salsa in its transnationalised form. There are also unpredictable relationships between music forms and dance forms, such as between zouk the music and kizomba the dance style. The infinite possibilities of permutation and combination within the wider Afro-diasporic world and the return of these rhythms to Africa is what enables people like Zahir and Miguel to flourish in the work they do. Yet they insist they are motivated by business, not music. They refuse to call themselves pioneers, insisting that they follow and capitalise on rather than initiate trends. Yet it was Zahir’s Grupo Chiado that first got the Angolan semba genius Paulo Flores to perform in Portugal in 2005. If that is not trend-setting I don’t know what is.

When I asked Zahir about whether his Indian heritage has influenced his career, he emphatically insisted on a ‘separation’ between his Indian-ness and his life in musical promotion. This word, ‘separação’, recurred in our conversation, leaving a faintly melancholic trace. Yes he had been to Gujarat in India, but he found it not to his taste—‘too conservative’. He began humming the tune of a song by a contemporary Indian pop star that he really liked, but he could remember the name of neither the singer nor the song (neither could I recognise the fragment of the tune). Where did he hear it, I asked? He looked at me as if that was the silliest question ever. ‘Just all around us, in Mozambique.’ Music and movement lives in the world. How it moves around the world depends on the conjunction of people and processes, geographical histories of cultural encounter, and, those unpredictable ingredients: personal genius and interpersonal relationships.

From people like Zahir Assanali I take away an incredible amount of inspiration and food for thought. Zahir chose to present himself in the context of friendship with Miguel, a white Portuguese man who has worked with the hottest acts in Afro-Brazilian music, knows the Carnival in Brazil, and speaks of the new taste for ‘black music’ amongst (white) Portuguese youth. Zahir is an Indian Ocean man with Africa and India both part of his identity. What sense does race make in these interpersonal connections? What precisely is ‘black’, ‘white’, ‘Indian’, ‘African’?—do these words mean something different when we apply them to skin colour, to physical features, to culture, to the beat, to the groove? And in analysing Zahir and Miguel and their work, I realised that I, too, had presented myself with a friend—an Italian woman who lives and dances in Lisbon and whom I have met through this increasingly tangled web of dancers interested in cultural analysis and cultural analysers interested in dance.

What we all had in common was an interest and passion in the Luso-Afro beat. We are, I guess, my definition of ‘AfroPolitans’: people who embrace African-heritage music, movement and style irrespective of racial heritage. Music follows many things, said Miguel Angelo in our conversation. ‘It follows politics, economics….’ Yes, but he left the most obvious element out. Music, and dance, also follows friendship, and the way human beings feel about, relate to, and connect with each other.

All photos of the Ilha de Mocambique and Cascais by Ananya Kabir.

Muito obrigada Francesca Negro, Zahir Assanali, e Sofia Martinho.

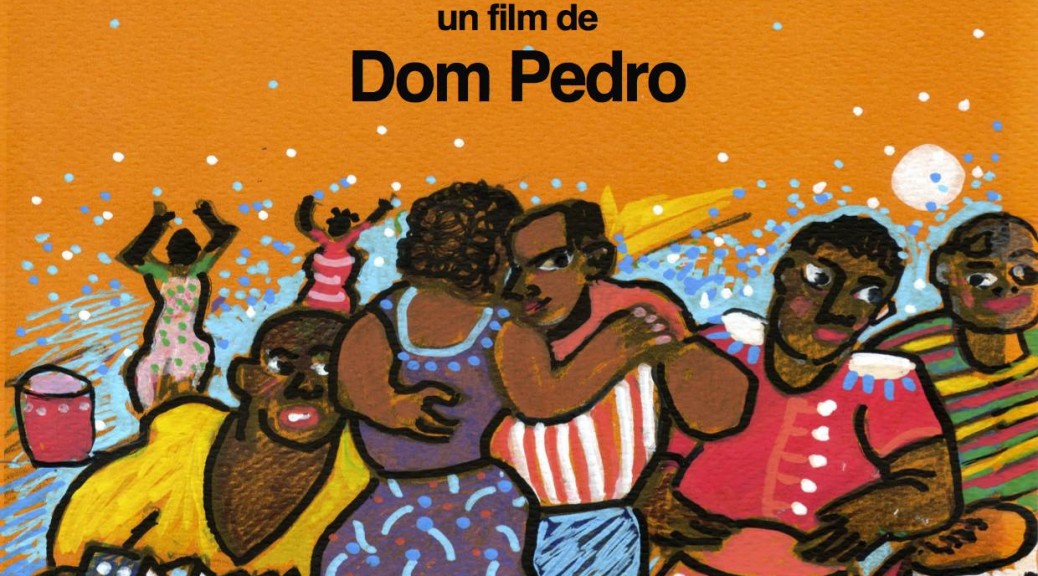

Featured image: Traditional dance in the shadow of Vasco Da Gama at the Ilha de Moçambique.

![The DJ works his magic. [Photo By Lily Boyce]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/taproom-top.jpg)

![The author and friends gather by the DJ booth in the infamous Taproom [Photo credit: Audra Allen]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Tap-floor.jpg)

![The vibe on the floor [Photo cred: Lily Boyce.]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/dance-1.jpg)

![The author, caught in a dance trance with friends Photo credit: Audra Allen]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Tap-floor-two.jpg)

![One of the more magic party moments [Photo cred: Audra Allen]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Tap-floor-3.jpg)

![Photo 3 - Rumba at Callejon de Hamel[1]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Photo-3-Rumba-at-Callejon-de-Hamel11.png)

![Photo 5- Altar for Yemaya[1]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Photo-5-Altar-for-Yemaya1-739x1024.jpg)

![Photo 6[2]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Photo-62-1024x768.jpg)

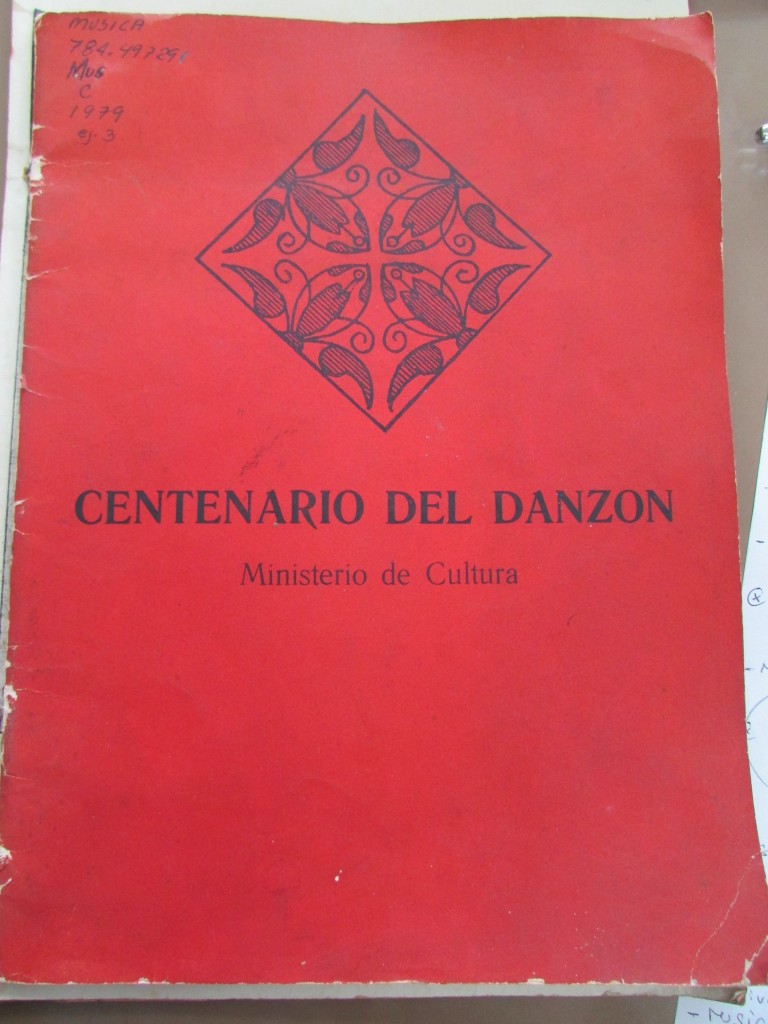

![Photo 7- Africa habla en mi[1]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Photo-7-Africa-habla-en-mi1-790x1024.jpg)