‘…pas de mot pour traduire ce terme; c’est plutôt un ensemble : plein de vie, qui va dans tout les sens, qui nous met la tête à l’envers …. En fait la fête de la Saint Jean c’est déjà une “coquinerie” ou chacun s’éclate et laisse sortir les émotions dans une danse à contre temps, des sauts des cris, des coups de sifflets, des coups de hanches et de bassin, entre tambours endiablés et bateau fou. Voilà un petit aperçu du tableau où s’enracine le terme de “revoltiod”‘

…there is no exact translation; it’s always already a multiciplicity of meanings. Full of life, that courses through all the senses, that turns us upside-down… in fact, the feast of St John is already a roguery where everyone explodes and releases their emotions in a dance against time, the leaps, the cries, the whistles, the bumping of hips and pelvis, between the swinging drums and the crazy boat. There- you have a little glimpse now into the scene within which is rooted the term ‘revoltiod’

Avelina Merkel, Cape Verdean artiste, explaining the phrase ‘Sanjon revoltiod’

“In addition to being mesmerized by the striking landscapes of Cape Verde’s islands and getting a first-hand experience of the rich music dance genres of the archipelago, one of the highlights of the stay has for me been the discovery of a music dance genre I was completely ignorant of so far: Kola sanjon. Associated with the celebrations of Sao Joao (Saint John) on the 24th of June in the islands of Santo Antao, Sao Nicolau and Sao Vicente, it is performed in couple and consists mainly of a step combination leading to the kola, that is the touch of the partners’ bellies. Although I knew a bit about funana, morna, coladeira, batuku, the main music genres associated to Cape Verde to which I listened to and read about beforehand, I do not think I had ever heard or read about Kola sanjon. Or if I came across this name in some of my readings or heard it in a way or another, it seemingly did not leave an imprint, which I obviously find rather intriguing in retrospect.

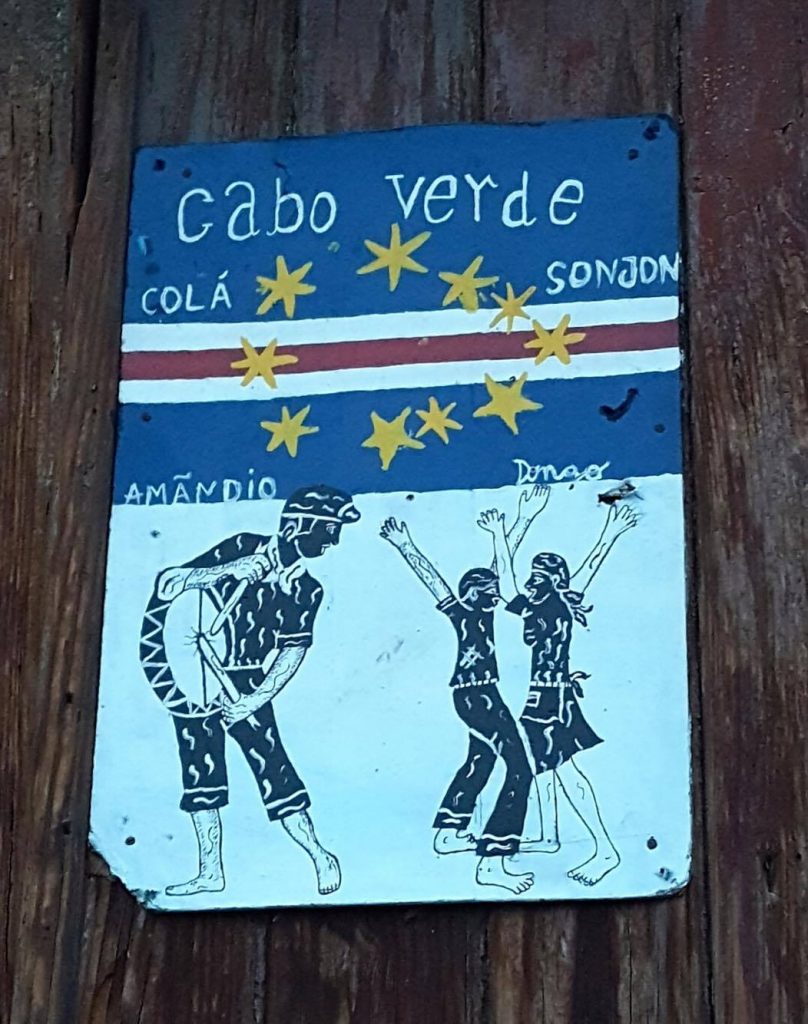

The first encounter I had with this music dance genre was in the Cape Verde national archives in Praia. In the exhibition space was displayed among other artefacts an envelope adorned with stamps featuring various Cape Verdean dance genres: batuku, contradança, tabanka and kola sanjon. The image featured on the kola sanjon stamp was also repeated on a corner of the envelope. I immediately noticed that the design represented the two dancers, a male and a female, caught in a dance figure that looked like a kind of umbigada (“navel touch”), one of the shared features of the Lusophone dance world, from Angola to Brazil (and also seen in the bele and gwoka dances of the French Antilles). The stamp also showed a drummer in the background. I was very enthusiastic with this “discovery” and I remember telling Ananya about this with excitement when coming back from the archives! She could provide me with further information about it and I was really keen to find out more and more and if possible, seeing it en vivo during our stay.

This “discovery” happened just the day after we attended for the first time a a batuku performance in Santiago’s Cidade Velha, the oldest urbanised colonial city built by the Portuguese in the 15th century. I had been struck by the bare-hand drumming on cloth and call and response singing performed by a group of young women and their trance-like gaze looking at the sky when they were dancing. I do not know how but I felt that something as enigmatic and powerful might lie in and link this two forms together – and indeed they are as I would discover it later on. Maybe because another stamp featured batuku on the envelope, maybe because a long-awaited encounter with batuku that just happened the day before was still resonating in me, maybe because this unexpected “discovery” sounded so promising, but since that moment, the mysterious kola sanjon took place in my imaginary and definitely whetted my research appetite. I was indeed looking for traces of it everywhere, getting for instance excited when I saw a flyer on an old door of a seemingly deserted house in a street of Porto Novo in the island of Santo Antao.

Therefore, I could not be happier when one of the Cape Verdean dance workshops we did as part of the Spirit of Cape Verde Dance and Cultural Holidays organised by Marie Doyen (MD Entertainments) in Mindelo (Sao Vicente island) was dedicated to this dance form. During the class we learned the steps and we were soon able to joyfully bump against each together while feeling the proximity with the batuku rhythm. Some batuku dance moments are indeed intertwined within the kola sanjon performance, definitely linking the two forms together. During a demo at the end of the class, the teachers and another couple performed together, showing us how this couple dance can be accomplished by imbricating two couples with one another, creating playfulness and improvisation within a set of dance patterns. As we were standing in a circle around them, we were suddenly being one by one “kolasanjoned” by other dancers. We could feel the exhilaration pervading the room. Yet this class was only a taster of another experience that arose a couple of days later.

While enjoying the beautiful sunset on Laginha Beach in Mindelo, the crowd was dancing kizomba on the open-air dance space of Caravela. Suddenly the DJ changed the music mood and started to put some songs to which we danced during the preceding Cape Verdean dance workshops: funana, mazurka and then kola sanjon. The crowd immediately responded to the musical injunctions by performing the dance moves accordingly. A palpable feverish climax built up among the dancing bodies. The experience of dancing Kola sanjon with the sunset as a background and the shadow of Monte Cara on one side and Santo Antao looming in the distance on the other, bringing batuku in the middle of the dance, was just breath-taking, in every senses by the way. So much joy, play, exhilaration, so much creative possibilities in improvising steps in-between the regular umbigada figure which you can also play with! This was surely one of my best dance moments I ever had and I am now looking forward to the next opportunity of “kolasanjoning” to feel the powerful magic of the dance yet again.”

Elina Djebbari, reporting on Modern Moves’s first research visit to Cape Verde in October 2016

Kola sanjon pulled Modern Moves back to Cape Verde in June 2017 to experience the full week of Festa sanjon celebrations in Santo Antão island. Sadly, Elina Djebbari could not join this return visit, but Modern Moves research associate Francesca Negro joined Ananya Kabir on a ten day visit to the islands of Sao Vicente and Santo Antão. As in November, the visit was organised by Marie Doyen of Spirit of Cape Verde and MD Entertainments. The intention was to study the Festa sanjon through total immersion in all its events and activities, including, of course, observing and participating in Kola sanjon dancing. In fulfilling this research brief, we were also able to experience first hand how an island celebrates its long history of creolization through reactivating the spirit of carnival- not just during carnival itself, but moments such as the Feast of St John, when, traditionally, sacred and secular revelry are locked in their own dance. This account draws on Ananya Kabir’s field notes during the week.

21st June 2017

We arrived into Sao Vicente airport with Kassav’ band members and Don Kikas on the plane with us. At Cesaria Evora airport there were representatives of local tourist agencies presenting arriving passengers with locally made ‘rozar do Sanjon’ . These ‘rosaries of St John’ are made of coloured streamers (like in Bahia, Brazil), popcorn (also as seen in Bahia!), groundnuts in their shells, and cacao beans, denoting a syncretism between Christianity and labour (of the African descendant population).

As we disembarked from the ferry, we were greeted by a demonstration of the dance associated with the festival, kola sanjon—characterised by strong ‘kolas’ or ‘umbigadas’ (belly buttom bumping in synchronicity with the percussion). As this was one African-derived move in social dances that missionaries universally hated, it’s amazing to see it at the centrepiece of a dance for the feast of St John the Baptist, but then the festival itself is synchronised with the ‘pagan’ rites of the summer solstice, so what’s a few umbigadas between us and the saint?!

In Porto Novo, we were received by Luis Carlos, our guide, who tookus to our accommodation: the simple and lovely Casa de France. Run by a Frenchman who has been in Santo Antão for over ten years and his Capeverdean wife, it opened directly out on an almost deserted beach of black volcanic sand. All food was cooked on the premises by Yann’s wife Iramita, and it was fresh and delicious, mostly just grilled fish and vegetables, with the fish caught locally and sometimes even brought to the door of the dining area and kitchen by fishermen in wetsuits whose boat was anchored minutes from the beach.

The first evening we attended the warming up festivities at the Aldeia Cultural (a faux ‘African’ village constructed for cultural activities) at Porto Novo, Santo Antão. A local band was playing funked up covers of traditional Capeverdean songs and popular Brazilian numbers, their music mixing with the sounds of the sanjon drums – which remind me of the tassa drums of the Caribbean and Mauritius– outside in the street. A pair of bulls worked the trapiche (sugarcane press) in the middle of the enclosure while two men fanned the furnace where rum was being prepared from the juice.

Families with children hung out, enjoying the music, chatting, eating the typical snacks for the feast (Funguim— banana and sweet potato fritters and pasteis do milho (cornflour patties filled with tuna)—and drinking bondaie, or slightly fermented sugarcane juice with ice. We saw stylised representations of the major figures of the festival (see the feature image)—not just dancers engaged in the classic kola moment with bellies touching and arms outstretched, but a drummer and a trickster-like figure of a man merged with a sailboat, whose task it seems to be to weave in and out of dancing couples in the kola sanjon (as we saw in the dance demonstration at the docks).

The whole place was vibrating with festive energy and the agricultural, maritime, Christian, and African elements that went into its mix were strongly palpable. Our Afro-diasporic social dances are at heart, social. Research of such festivals reminds us of the organic world in which they developed and grew before moving out to the dance floor. A very important part of this world are moments of celebration and syncretism where the Christian calendar could allow a pause in the rhythms of labour which were then replaced momentarily by transgressive and joyous dance, music, and play of different kinds drawn from diverse cultural heritages: the creolized carnivalesque lives and thrives in this annual revival.

22nd June 2017

This was the evening of the processions for St John in Porto Novo, Santo Antão. The processions were supposed to start at 8 pm but at 8.30, when we arrived, things were still in a state of preparation. The main street of Porto Novo was cordoned off for about 500 m. People were already lining both sides of the street in anticipation. There were two sets of seating: an ordinary and a VIP option. Behind the seating, a huge banner proclaimed the events of the week, with a special focus on Kassav’ as the star act. A gigantic cut-out of the four figures of Sao Joao—two dancers, one drummer, and the ‘barquinho/ navim’ (the trickster man-boat)— also towered over the seats.

A DJ played a succession of what one could call Sao Joao pop music—contemporary songs using the Sao Joao rhythm (often electronically) and lyrics alluding to the festival– such as Gil Semedo’s ‘Maria Julia’. On the sidewalks, men gambled small change at the numerous tables set up for the local game of banka, while women sold a variety of pasteis and popcorn from makeshift stalls. People were gathering with their families on either side of the street and the air was lively with anticipation. The procession is also a competition, so the MC kept reminding us about the rules and criteria for judging. We were going to see six groups and each had between 15 and 30 minutes to present themselves. They would be judged on their creativity, dance prowess, and the quality of the drumming.

At 9 pm, the prime minister of Cape Verde arrived together with some other dignitaries, and the coast was clear for the first group to process forward. From the village of Ribeira das Patas, they were the prize winners from last year. We pressed forward to see them, cameras at the ready. The sound of the tambores filled the air, mixing with the MC’s commentary. As the group moved to the centre of the processing space, all could see from our vantage points was a veritable forest of green stalks (‘ramas do sanjon’) of sugarcane, festooned with bunches of purple flowers. People were dressed in peasant clothes of yore and dancers old and young moved to the beat of san jon, turning towards and away from each other but always connecting rhythmically on the fourth count through the ‘kola’. Through contrapuntal high pitched whistling, the energy levels rose ever higher.

An old man led the procession in a position reminiscent of the Brazilian carnival’s ‘comissão do frente’. There was also a donkey in the mix. Three ‘barquinhos’—men who ‘wore’ the boats, coloured streamers fluttering from their masts in the shape of sails, wove in and out of the dancing couples. Another character, with a suitcase in one hand and a calabash water bottle in the other, represented, according to our guide Luis, the Capeverdean diaspora. A mise-en-scene facing the VIP enclosure, presented a miniaturised version of a farmer’s homestead, with tools and implements including a sewing machine, hurricane lamp, clay pots for water and other items, and a mattress made of a plastic sack filled with leaves.

The dancers congregated in front of this scenario, showing off their best moves to the VIP guests and judges. As they moved towards us, the drumming became louder, the green stalks loomed larger, the barquinhos veered ever more crazily, and the kolas between the couples became stronger. The whole was hypnotic and heady, and this was only the first group! After they processed out, the DJ took over and played a succession of mixes of old and new ‘sanjon pop’. The rest of the groups presented variations on this theme, with the second, for instance, changing the mise-en-scene to the representation of a miniature church. Each group was also distinguished by the specific way they decorated their ramas, but those of the first group, towering green and puple above the crowd, will always remain vivid in my mind.

After the first three groups had processed, with the DJs playing in the intervals between them, it appeared that adjustments had to be made in the interest of time. Consequently, the remaining groups came on together in a single, glorious mega-procession. I could observe close-up the ways in which dancers both enjoyed the simplicity of the sanjon structure and introduced variants in their movements during the moments before the pairs came together for the kola. The movement repertoire was angular rather than flowing, with the arms held close to the body except for the moment of the kola when they are raised in synchronicity to the belly-bump. The effect is capricious, even child-like, accentuated by the barquinhos weaving in and out of the couples.

As the old cobblestones of Avenida Amilcar Cabral reverberated with drumbeats and kolas, what struck me most was the intensely familiar and family atmosphere of the event. Everybody was out with children, and the parents and even grandparents, were strikingly youthful. While waiting for the groups, adults chatted with each other and children played together, very often kola sanjoning together. Even one and two year olds were dancing with each other: if you could walk, you could kola sanjon, seemed to be the consensus. I saw young mothers dancing with the babies in their laps, or with their toddlers. This deep immersion of the entire population in the rhythm of this festival was the way in which the community ensured the cultural education of children, and passed on dance as a resilient form of cultural memory.

23rd June 2017

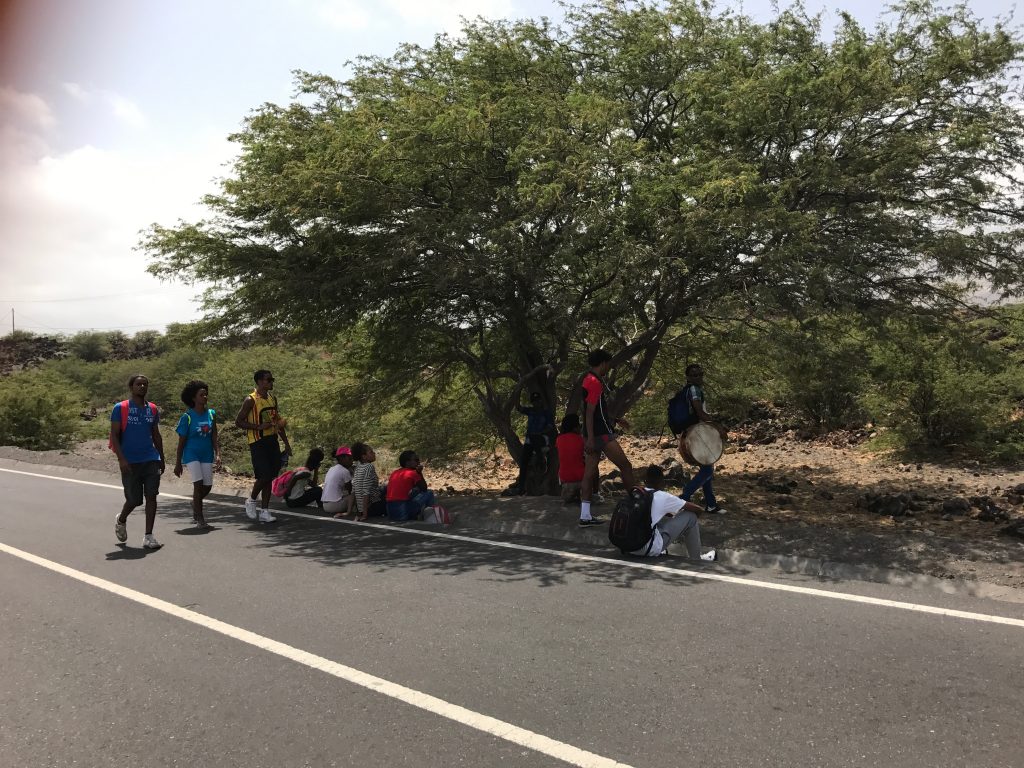

This was the day of the pilgrimage of St John/ Sanjon: the annual return, but for one day only, of an icon of the saint from Ribeira das Patas down to Porto Novo, accompanied by revellers, drummers, dancers, and people bearing ramas as their individualised offerings to him. We were dissuaded from starting the procession at Ribeira das Patas, as we had brought with us neither footwear deemed appropriate for a 23 km walk, nor hats to shade us from the sun. Moreover, as we were staying just outside Porto Novo, it would entail a journey to Ribeira das Patas in time for the procession’s 7 am start. Our guide persuaded us that the best thing would be to join the procession mid-way around 2 pm, when the pilgrims would have hit the halfway mark. A taxi took us to the agreed point and we disembarked in the middle of the highway in the glare of the afternoon sun, sporting our Festa sanjon t-shirts and crossed-draped rozars.

It was, however, surprisingly comfortable. The road was elevated, running down to the sea on our right and rising up to mountain slopes on our left. The stark landscape and scanty vegetation enabled a pleasant breeze to blow unimpeded from the seashore to us. Behind and before us were groups walking, beating drums, drinking beer, singing. The main part of the procession, centring on those bearing the saint, were so far behind that we could neither see nor hear them. We fell into step with some groups, others fell behind, yet others passed ahead of us, only to stop to rest in the shade of a welcome tree. We passed several such resting groups, which included cows, donkeys, and goats also enjoying the shade.

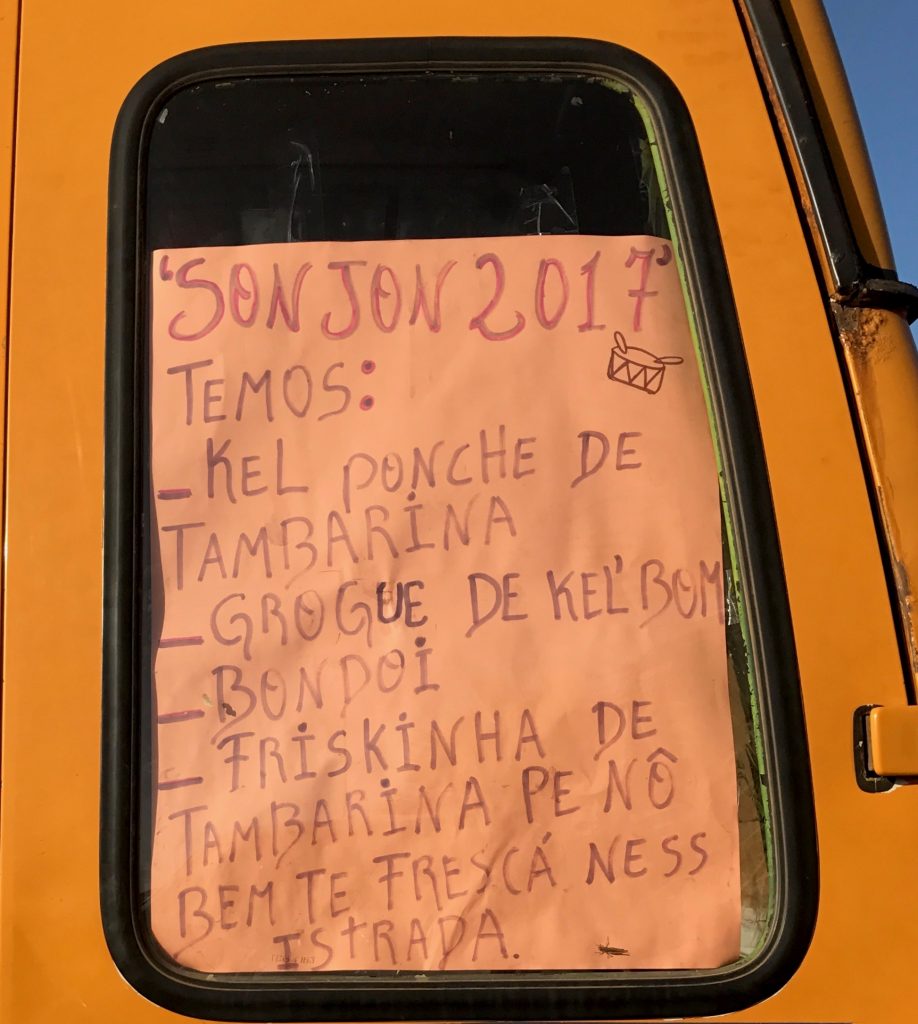

Young men flirted with us as they passed us by, serenading us with lyrics of songs. I recognised ‘rainha do Holanda’ by the Santo Antao group Cordas do Sol! Every now and then, a woman stood by the roadside with an icebox full of delicious homemade tamarind flavoured ice-lollies (fresquinha do tamarindo). The only problem with these, as far as I could see, was the environmental pollution the thin plastic sacs caused after the sweet and sour ice crystals were sucked out of a hole you’d tear in the corner with your teeth. There were no bins or any other waste disposal arrangements, and the entire route was littered with wispy bits of plastic from all the fresquinhas consumed en route by people since the morning. Bonded by soundtrack, occasional shade, fresquinhas, and the Sanjon Tshirts and rozars that we were all wearing, we participated in a relaxed and good humoured fellowship of the road.

About a couple of kilometres from town, the people on the road started growing more numerous and we could hear the drums of Sanjon getting louder. The pilgrims were amassing around a small white chapel to the left of the road. Although it was a modern construction, the kapelinha da aga doce (small chapel of the sweet waters) was evidently an established part of the route as the waiting post for the crowd to congregate and eventually catch up with St John. Resourceful women, including Luis’s wife, her mother, and her grandmother, had set up stalls under the shade of trees. On trestle tables were snacks and sweets, rozars were draped from tree branches, and iceboxes contained beer, soft drinks, tetrapak juices, and fresqinhas. Vans hawked bondaie, punch, grogue, and cachupa. Inside, devotees lit candles and prayed. Outside, young people danced to different groups of drummers. Old ladies dressed in their best stood waited, holding upright their beautifully decorated ramas. Children ran around or slept in the arms and laps of elders.

After about an hour of this convivial waiting, one sensed a growing excitement. People started moving to the two sides of the road. Different drumbeats converged in an orchestra of further and nearer sounds. St John was coming closer! We edged to a vantage point, teetering on an incline and craning our necks. People obligingly parted to let us have the best view possible. Soon, we were swept along an immense river of devotees. About 20,000 people fell into step as the procession moved along the highway that became the single cobbled street running through the heart of Porto Novo—the same Avenida Amilcar Cabral that we had lined the previous evening. The drums became hypnotic and people stepped up their energy, but no one pushed or bumped into each other. We were bound up by the singular rhythm, the crowd control of the drums, the accentuation of the whistles. As part of the procession, the dynamics of movement also became clear—a surging forward, then a moment of retrogression and the kola, then forward again.

Maintaining this staggered yet smooth flow, we approached the church in Porto Novo where St John would be installed for the night. People lined the old stone walls that ringed the Church square. Bunting streamed gaily between trees. Stacked ramas filled a corner of the church, flooding it with greenery and colour. Outside there was ice cream, beer, and more conviviality. Sanjon had arrived! During this procession, we heard and understood the meaning of the phrase ‘Sanjon revoltiod’- St John has returned, turned the tables, the world is in revolt, revelry is everywhere, the drums are sending people into ecstasy. That’s the spirit of carnival, and that’s what infuses the celebrations around ‘our Sanjon’.

The party continued during the evening, with the high point of the week : the Sanjon 2017 party at the old Amilcar Cabral stadium, which began at 11 pm and continued till long beyond sunrise the next morning. There were three big acts for this concert: Kassav’, from the French Caribbean, Loony Johnson, representing the Capeverdean diaspora in Rotterdam and their contribution to ‘Ghetto Zouk’, and Ferro Gaita, a neo-traditional Cape Verdean group that plays tabanka, funana, and other local genres in a more or less conservative style.

Three groups, three manifestations of Afro-diasporic rhythmc cultures as processes and products of creolization. The crowd synergy that I experienced during the procession was channelled here into the stadium—another, more ‘modern’ format, but the same flow and controlled yet sychronised movement- that which we are theorising in Modern Moves as ‘alegria’. Loony Johnson drove the young ladies of Cape Verde to distraction (their behaviour was somewhat reminiscent of the height of Beatlemania) and Ferro Gaita kept everyone jumping to the funana beat till the wee hours, but it was the opening act that took our breath away and enacted many of our Modern Moves theories around creolization as a global phenomenon.

What a pleasure and a privilege it was to enjoy Kassav’, the iconic Caribbean group that has performed and generated pan-Africanism through sound and movements, live in Africa! And that too, at a stadium named after Amilcar Cabral! In London two years ago, we had already heard first hand Jocelyne Beroard’s views on creolization as a political agenda and the reasons for Kassav”s incredible popularity in Africa. In Santo Antão, we saw both aspects of that story in action, though this is a story yet to be given its full due by academics of any kind: a band from a small francophone island in the Caribbean who won the hearts of a whole generation of Africans and who continue to resonate with young listeners. What does this say about the Black Atlantic and (post)pan-Africanism?

Kassav’ on stage in Cape Verde was creating a new Creole from the encounter of two creolised cultures and languages through the incredible energy and fabulous stage presence of a band whose members are now in their 60s but still going strong- and an audience of tens of thousands chanting and moving as one. Jocelyne addressed the crowd in French Creole and Jacob in a mixture of French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Krioulo. Everybody understood each other. ‘zouk is the only medicine we have’, they sang to close the concert, and the entire audience joined to chant this demotic anthem of postcolonial trauma and its resolution through collective ecstasy of the singing and dancing body.

24th and 25th June 2017

Night had flowed into morning over cachupa and the washing of our tired feet in the ocean’s waves at 7 am before going to bed. ‘Thousands of people are partying continuously since the 20th on this island’, I wrote in my field notes on the morning of the 24th ; ‘Whether processing or dancing or hanging out in the streets, they are in an extended collective trance where lucidity is enhanced by an awareness of community. No one is drunk, no one behaves badly, no one pushes and shoves. It’s impressive.’ The final two days of Festa sanjon were certainly recovery mode after the crescendo of the previous day. We missed the morning mass at the Church after which St John was returned to Ribeira das Patas, but we caught the traditional horse races on the beach in the afternoon, which seemed an excuse for more family style flanerie, sanjon pop blaring from beachside DJ booths, sanjon drums beating, fresquinhas, mangoes, ice creams, and grilled chicken.

There was a ‘smaller’ party, ‘nos sanjon’, in the Recinto de 5 Julio the evening of the 24th, with some equally big names from the world of PALOP music— notably, Cabo Verde’s own Grace Evora, and the Angolan singer of semba and kizomba, Don Kikas, whom we had already spotted on the flight from Lisbon. As we had noted earlier during our first field trip, familiarity with the soundtrack of kizomba does not mean that all Cape Verdeans dance kizomba ; however, they dance. People moved and swayed and came together to kola sanjon, and sung along and clapped.

The Recinta was open to the skies and we could see the stars and the moon and the dark night as we enjoyed the fantastic music in a more intimate atmosphere than the Stadium had allowed the previous night. ‘E sexta-feira’, we sang along with Don Kikas on stage, ‘tem bebedeira, a nossa maneira/ sexta feira, tem muita passada a nossa maneira’ (it’s Friday night, and we’ve got drinking and dancing lined up, in the way we like to do it best)’.

It wasn’t Friday night, but it was a moment, like Friday night, when work ryhthms are suspended and another rhythm takes over. So who was the ‘we’ of ‘nossa maneira’ (our way) ? Capeverdians such as Don Kikas’s audience, Angolans such as himself, or people like us who are, I guess, swept along the wave of a possible world creolisation, who are porous to the rhythms of alternative, afromodern time? Who is the community of revellers that succumb to Sanjon’s call ? Well, lucky that we got to ask Don Kikas himself the next day. Every time Modern Moves are in Cape Verde, we seem to have the opportunity to meet the most wonderful musicians from Angola and Cape Verde. Always magic in the air! On Sunday afternoon, then, when the whole town seemed to be sleeping in, we found Don Kikas at his hotel and conducted an in-depth interview with him about kizomba and semba, cachupa and funge, the iconic dishes of Cape Verde and Angola respectively, as signs of the relationship between these two countries, the politics of language, the importance of partying, and the difference between cultural appropriation and respect. Thank you Sao Joao !

In the evening, on the heels of Sanjon himself, we took the aluguer (communal van) to Ribeira das Patas, to experience joãozinho, (little St John), the traditional goodbye party. We were exhausted but for the inhabitants of Santo Antão, who seemed to have decamped en masse from Porto Novo and other settlements on the island to Ribeira das Patas, the party was only just beginning- it was just midnight ! As the music resounded and the smell of delicous grilled food wafted through the air, courting couples, wide-awake children, families and groups of friends filled the square where the aluguers deposited and picked up passengers. On an island in a volcanic and barren archipelago in the mid-Atlantic, Cape Verde, where the first creolized society anywhere in the world took shape in infelicitous and difficult circumstances, the stage was being set for the return of St John the following year.

And the return, too, of a feeling that our Cape Verdean friends describe to us as ‘out of control, but a good crazy’, ‘the moment when drums and dancers reach a state of total ecstasy’, ‘when the entire world is turned upside down, but in a good way.’

The carnival(esque) always returns. Sanjon revoltiod.

Ananya Kabir thanks Elina Djebbari, Francesca Negro, Marie Doyen, Luis Carlos, and all our Cape Verdean friends and colleagues. And thank you, Avelina Merkel, Dinana Pinto, Ary Machado, and Nelson Barbosa for helping us with the meaning of ‘revoltiod.’