Lambada, the so-called ‘forbidden dance’ from northeastern Brazil that swept through the world in 1989 through the music of Kaoma, has been one of the foundation stones of Modern Moves.

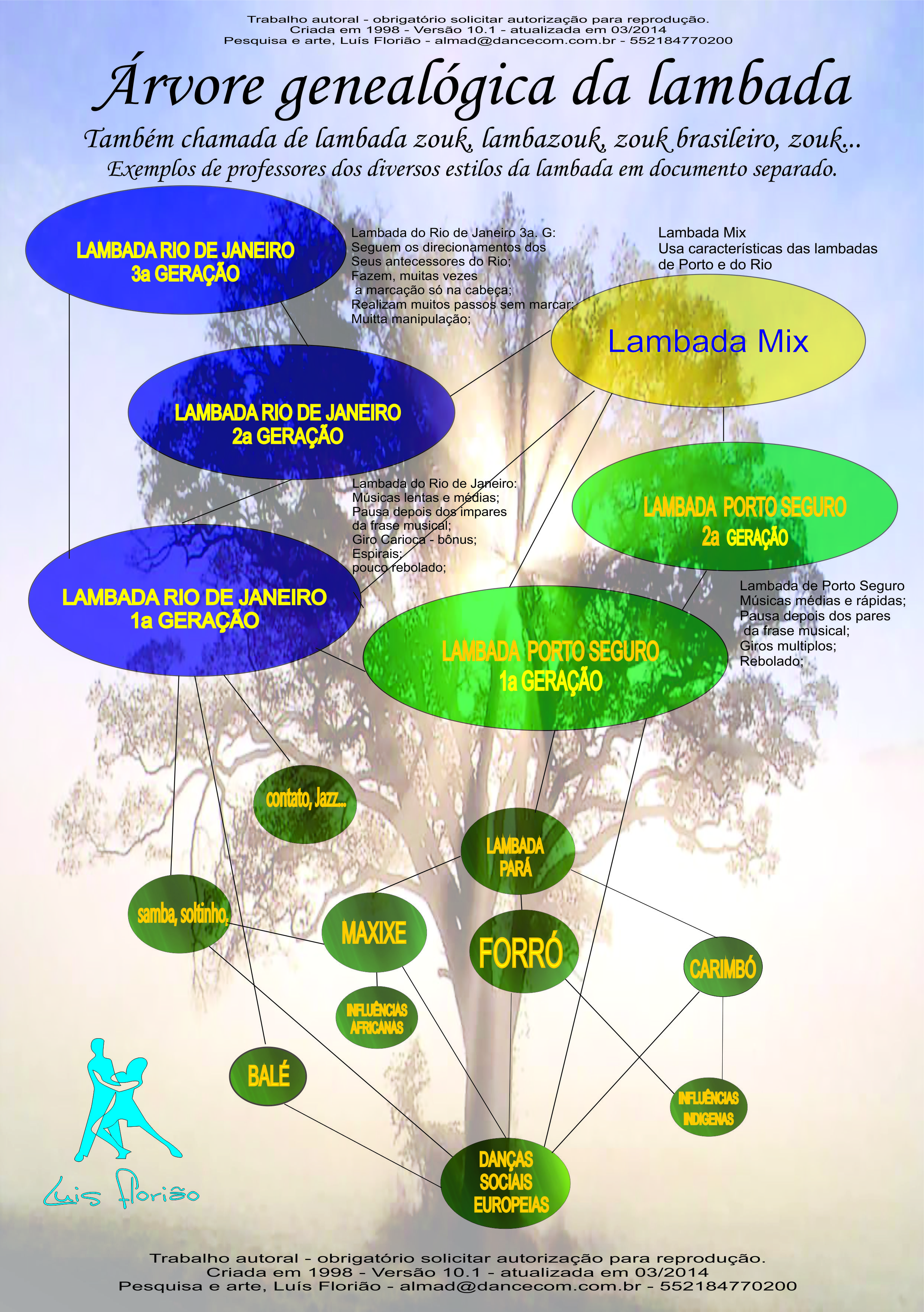

Since then, lambada has evolved into a number of dance styles that go under the umbrella term of ‘Brazilian zouk’. Through the usual network of dance studios, festivals and congresses, and dance socials, Brazilian zouk forms have become fully transnationalised.

Last summer, the dance drama Brazouka paid homage to lambada as the starting point of Brazilian zouk through the story of Braz dos Santos, one of the original dancers of the Kaoma videos. The Brazouka team carried further their engagement with lambada by organizing, together with Braz and his brother Didi dos Santos, the Brazouka Beach Festival in Porto Seguro from the 1st to the 9th of January.

What’s at stake in recreating the moment of origin through a social dance festival? Why go back to a small Brazilian town when a dance style was supposedly born, when its subsequent forms have become so international? What is being memorialised, and why? What are the scales of encounter between regional, national, and transnational? How is cosmopolitanism danced and how is the region remembered (or forgotten)? These are the reasons (and more) for our interest in this Festival.

Modern Moves sent our Associated Researcher MK Kim, a Brazilian zouk enthusiast, to attend the festival in Porto Seguro. Here’s an account of her first impressions:

On a mission to learn where Brazilian zouk comes from, my first stop is Porto Seguro, where lambada was the most popular dance in the 1980s before it had become a “forbidden dance”, banned because people thought it was too sensual.

Arriving at Porto Seguro in the morning of 2nd January, I was so eager to see with my own eyes the birthplace of lambada. I stopped at a local store for water and went straight to the beach. The ocean sounded, smelled, and looked surreal. This is the place where lambada arrived and which gave life to it.

While walking on the beach, I remembered that Holly, one of the Brazouka Beach festival’s organizing team, had said that the venue was located right by the beach. I asked few locals at the beach if they knew where the festival was. Nobody knew about the festival, but when I said lambada, they shouted “oh, lambada!” and pointed northwards.

I finally found the festival venue “Boca da Barra”, which used once upon a time to be a simple bar where people would drink and dance.

Nowadays, it’s a typical Brazilian venue: a semi-outdoor building bathed by a light sea breeze, where there is only ceiling but no wall, two wooden dance floors, a coconut water vendor, bar, food vendor, little alley to the beach and resting area. Mother nature, history and festival organizers seemed to have set up everything perfectly for us dancers.

The workshops were at the same dance floor as the parties and shows in the evening. They are mainly Lambazouk, and some ladies styling, men’s styling, samba funkeado, and kizomba. People take a break by going into water to cool off. If you don’t have a partner, you could do Capoeira with the ocean.

People usually say that Lambada/lambazouk is all about having fun. As soon as I walked into the venue, I was asked for a dance even before changing my shoes and constantly asked to dance the whole night. While sweating my life out from dancing outdoors with no cooling system in 30 degrees Celsius, I smelled and felt the ocean breeze, perhaps the same one that dancers felt in those clips from 1989, right here.

The parties are full of “energy boa” (good energy). Indeed, lambada is all about having fun. A woman dancing with two guys, a guy dancing with two women, “Oh, hey let’s dance!” “Oh, you told my woman? Who cares, I am going to do a little free styling till you are done, or I may steal yours.”

The performances that the Brazouka team has organized are breathtaking. The Brazouka Beach festival team have thought through the evolution that lambada underwent after the Porto Seguro era; they have awarded ‘Lifetime achievement awards’ to the dancers Jaime Aroxa and Adilio Porto who played a huge part in developing Brazilian zouk in Rio de Janeiro after the Porto Seguro phase.

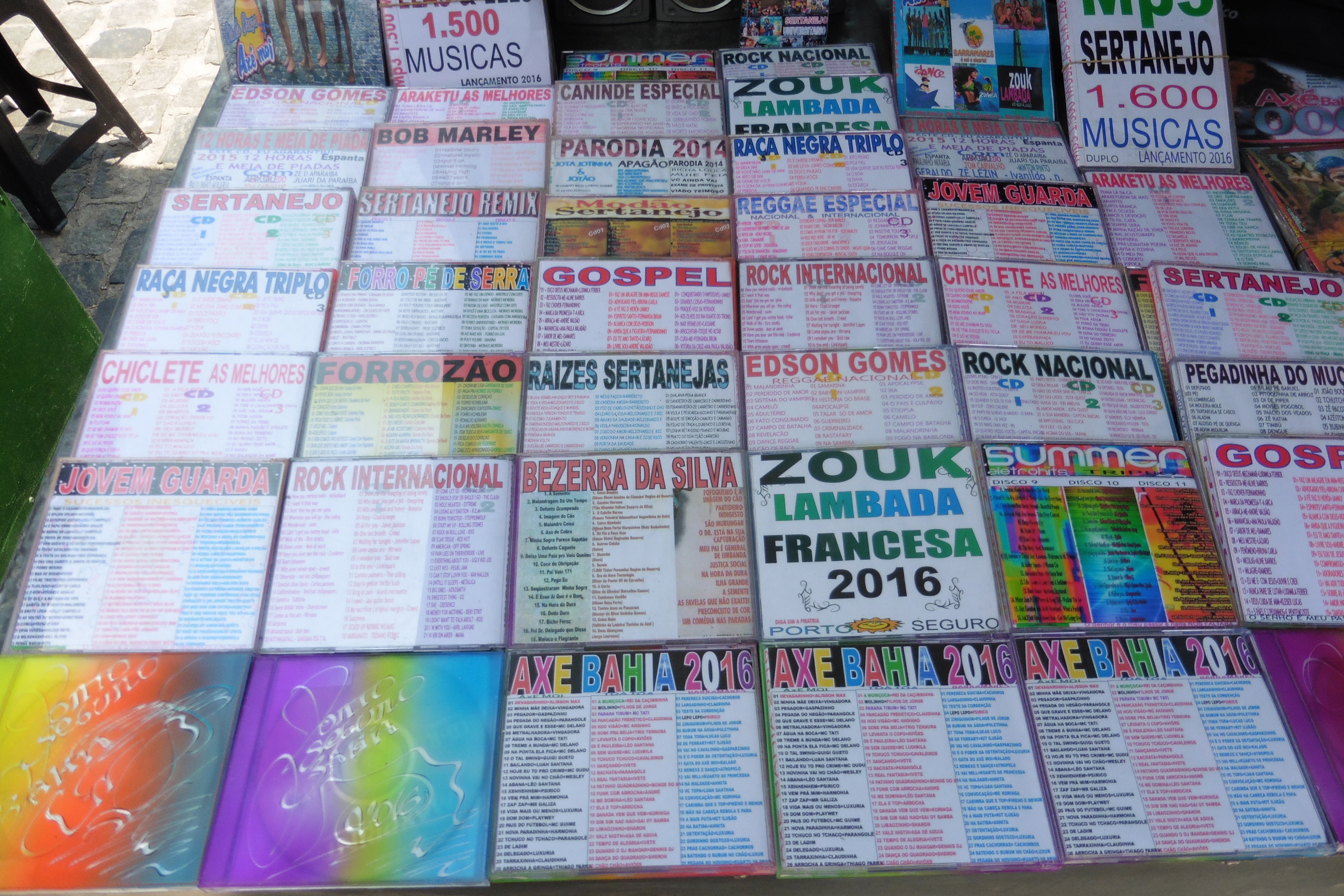

From the venue to the town: vendors and shops open along the beach every day. They sell souvenirs, sweets, beachwear and fresh coconut water. It’s a reminder of the history and what they represent and perceive the region as. People walking around, the way they remember and associate with the place, the street becomes a living museum.

Of course, the music vendors caught my eyes. They sell so many different types of music. The seller said the most popular are Bahia music albums – with no specific genre, but a mixture of all the music from Bahia, followed by Zouk and Lambada.

Every Sunday in Porto Seguro, people gather at the plaza in the city center for music and dance. There were lots of open restaurants at the plaza where people were enjoying a cooled down evening after the heat of the day. A stage with a DJ and band was set up in the plaza, in front of a tiled dance floor built into its middle. How fantastic!

When I arrived, a Forro band was playing and a few people were already dancing. Somebody told me with body language that Zouk will start at 10 pm. Around 10 pm, a Zouk DJ in his “Zouk music” hat from the Youtube music channel based in Brasilia arrived and dancers started to increase.

In the plaza right near the beach, with the smell of ocean mixed with fried fish, grilled meat, and beer, everybody was dancing. Dancers mostly gathered near the stage and they all seemed to know each other. I was also surprised at the range of the DJ’s music, from traditional Lambada, Zouk, and to updated Zouk remixes.

I don’t speak Portuguese and I am not used to Lambazouk, but that was not a problem. Everybody embraced everybody. A guy was dancing with a little girl, mom was dancing with her baby son holding him in her arms, and an older couple and young couple were dancing as well. Everybody was indeed just so happy to dance. It was like a celebration of the end of the week. Low key, with friends and family, yet filled with happiness and sharing the joy of life.

During our subsequent days in Porto Seguro—we learnt many things that corrected and complicated these initial impressions. Was it 40 years ago that lambada was ‘born’ (as announcements during the festival’s opening claimed) or 30 years ago (as the festival tshirts proclaimed)? The venue was named ‘Boca da barra’ but the original Boca da Barra was now a gas station and young employees there remembered only the new venue when they heard the name. Didi dos Santos, the brother who stayed behind (Braz lives in London now) revealed to us that the sources of inspiration for the turns and dips he introduced into lambada were the films ‘salsa’ and ‘dirty dancing’, while the basis of its footwork lay in the Brazilian dances forro, baiao, even maxixe…

So is lambada a Caribbean dance or a Brazilian dance? Both possibilities were articulated by Didi at different times during our conversation. ‘A Caribbean dance with a ‘sotaque brasileiro’ (Brazilian accent) is what I hazarded as a compromise. To my delight, Didi enthusiastically agreed.

All photos by MK Kim unless otherwise indicated.

Italicised text by Ananya Kabir; the rest by MK Kim

We thank Holly Middleton, Luis Floriao, Didi Dos Santos, and each other.

![P1000708[1]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/P10007081.jpg)

![Picture 005[1]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Picture-0051.jpg)