On Lemonade, the sixth studio album and second visual album by cultural powerhouse Beyoncé, we are in many ways re-introduced to the creativity of a singer who has been with us for 15 years already – the same singer who gave us “Bootylicious” and “Bills, Bills, Bills.” Only this time, she’s not here to entertain: she’s here to take creative risks.

One of the excellent things about Lemonade, and there are many, is how the record shows Beyoncé pushing her voice and musical palette to explore new and uncharted musical territory. Lemonade production and song writing credits come from the likes of unexpected people like Jack White of The White Stripes and British singer songwriter James Blake. These are two of my favourite musicians but I never, ever thought in a million years they would work on a Beyoncé record, mostly because the music she makes often gets catalogued in music stores as R&B or hip-hop, or as “black” music, whereas The White Stripes have always been seen as alternative or indie rock, or “white” music, despite the fact that rock and roll was black music first.

“Daddy Lessons,” one of the twelve excellent tracks from Lemonade, is by far the stand out number of the bunch. It’s my favourite anyway, the one I keep playing over and over. In it, hand claps and a roaring saxophone capture the summer sun and sitting out on a sun kissed porch allure. We hear the uplifting spirit of New Orleans jazz before an enthusiastic female voice comes in to add just a splash of ambiance.

“YEEEEEEEE HAWW!” she sings, a reference to the stereotypical vocal flourish of country music. “Texas,” Beyoncé says three times, in case you didn’t hear her the first two, repeating herself specifically to locate herself in the Black American south.

“Daddy Lessons” is a straight up bluegrass track and for the life of me I never imagined that Beyoncé would ever make a country record or a bluegrass track, let alone one that works really well and doesn’t feel forced or as though it’s trying too hard. There is, of course, a long history of black Americans making country music before it got whitened, one of the major takeaway points of last year’s the Modern Moves research trip to the Rock and Soul Museum in Memphis,

Aside from its strokes of musical genius, like the painful vocals in the sparsely colored “Sandcastles” or the “Tonight I’m fucking up all your shit, boy!” piping hot urgency of the Jack White-assisted “Don’t Hurt Yourself,” where Lemonade stands out especially well is in how it offers a highly polished, highly editorial, high art version of Beyoncé. This is a Beyoncé who channels Yoruba goddess Oshun in “Hold Up,” and who has surrounded herself with an intergenerational cast of women of color.

This is Beyoncé 3.0, a Beyoncé who is above making music for the radio, above churning out “hit singles” and what record labels want her to do. We already know she can dance. We know she can sing. We know she can pen a chart topping single and start a dance craze in seconds.

“I might get your song played on the radio station,” she boasts on the pro-Black anthem “Formation,” the last track on the album.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lMAISeUGcyY

But her swerve away from traditional measures of musical success actually gives us an experimental Beyoncé, one who takes her own musical and creative risks. Lemonade is a visual album – you really need to see it before you hear it – and was released first as an HBO special on April 23, 2016, available for streaming and download shortly after. The effect of such a visual album is that we are forced to sit down and engage with it as a whole piece of work rather than as an assortment of singles surrounded but a bunch of other songs.

And in it’s visuality Lemonade is stunning, it’s message made explicit visually explicit. You could watch Lemonade with the sound off and still understand its politics. For instance, the very first image of Beyoncé is of her out in a field wearing a hoodie, an unsubtle link to the BlackLivesMatter movement and Trayvon Martin as well as a way of locating her black/creole body in the iconography of slavery.

But perhaps the moments that sum up what Lemonade is about are all of the close, tight shots of women – black women – standing completely motionless. They stand alone, motionless, and stare down the barrel of the camera, motionless. They stand in groups, motionless, and even when they’re in groups they are still motionless. These long, deliberate shots of motionless women of color has the effect of elevating them, valorizing women of color, their beauty and personhood. Film critic Laura Mulvey famously critiqued cinema for the way it frames women as “to be looked at.” But here, the women are actually looking back at us just as much if not more than we are looking at them. This is a return of the gaze, where standing completely still becomes an an act of resistance.

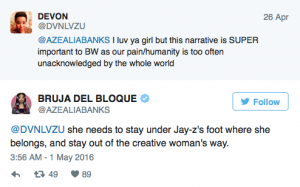

Of course, like all good art, Lemonade has its naysayers and harsh critics. New York rapper Azealia Banks, infamous for her Twitter beefs with just about everyone, pointed out that all of the songs on the album are about heterosexual coupledom, heartache, heartbreak, cheating, essentially begging a man to love her. Specifically, she said that Beyoncé needs to “stay under Jay-Z’s foot”:

Banks surely has a point. Here’s an album about black women, femaleness and womanlihood that is all about getting back at her man for cheating on her, so far as attacking “Becky with the good hair.” But part of me wonders if this is just not part of the genre of love songs, songs that are always about the cycle of love and heartbreak.

If a man sang these songs – say, D’Angelo – would we read them any differently? Would we approach and critique them any differently?

The fact that Lemonade can be problematic in places and stunningly beautiful everywhere else – it is a work that is “both” “and” – attests to its value as art. Good art is always complicated and stages more questions than answers.

MADISON MOORE