When I was in graduate school I spent nearly all of my free time in New York City. If I wasn’t in coursework then I was in the train to the city or I was coming back from the city, usually because I’d been pumping through nightclubs in the East Village. There was always a last train from New Haven, around midnight, and a first train back, usually around 5am. It didn’t go unnoticed among my cohort, who regularly asked me, with an erudite yet judgemental tone, how I was able to find the time to do all my seminar work and go to New York City so much. The implication, of course, was that I wasn’t working hard enough, that I didn’t take graduate school or academia seriously because I always found my way to the party.

At the time, I didn’t realize that nightlife and club culture would eventually become my research project or that the narrative of pleasure versus the perceived torment of real intellectual labor would power the conversation about night worlds. So I got the idea to propose a special junior seminar for undergraduates about nightlife culture in New York City. The course was a hit. My students loved it, they loved the guest speakers I brought to campus, and they loved the field trips we took as part of the course.

Things got a bit more complicated, though, when the gossip tabloids got a whiff of the seminar, splashing it across headlines around the internet, including the Daily Mail, dragging my name as well as the University’s into the mud. I even got emails from prominent alumni who shamed me for teaching such nonsense and for me bringing the University’s name into the mud myself. And that’s when I realised that I was onto something with nightlife. There are a number of ways to study history, culture, social change, race, gender and sexuality, and the nightclub is one place to do it.

In certain academic circles, the pursuit of nightlife is seen as being all fun and no research, like I imagine some of the people I knew in grad school felt about what I was doing. The work is doubly unserious and unrigorous if it does not come from an identifiable archive or library holding. You’re not supposed to be having so much fun. This sentiment is less so in places like performance studies, American Studies and queer of color studies, where researchers of nightlife are actually on the rise. But as with any scholarship about the margins, which flips a canon on its head, the hardest task is proving you’re right and proving you’re right. I agree with Jack Halberstam’s notion of “low” theory, which he sees as an undoing of the traditional canon or archive, a privileging of “low” culture over high culture.

Fear and condemnation of nightlife is real and stretches from the church to city hall, and from your parents to the media. More than that, it’s a fear that reaches across time and space. In the early 20th century, for instance, a young New York girl called Eugenia Kelly was arrested after a weekend getaway upstate because her mother thought she partied too hard. Can you imagine? Mrs. Kelly actually wanted to have her daughter institutionalised because she partied a bit too much.

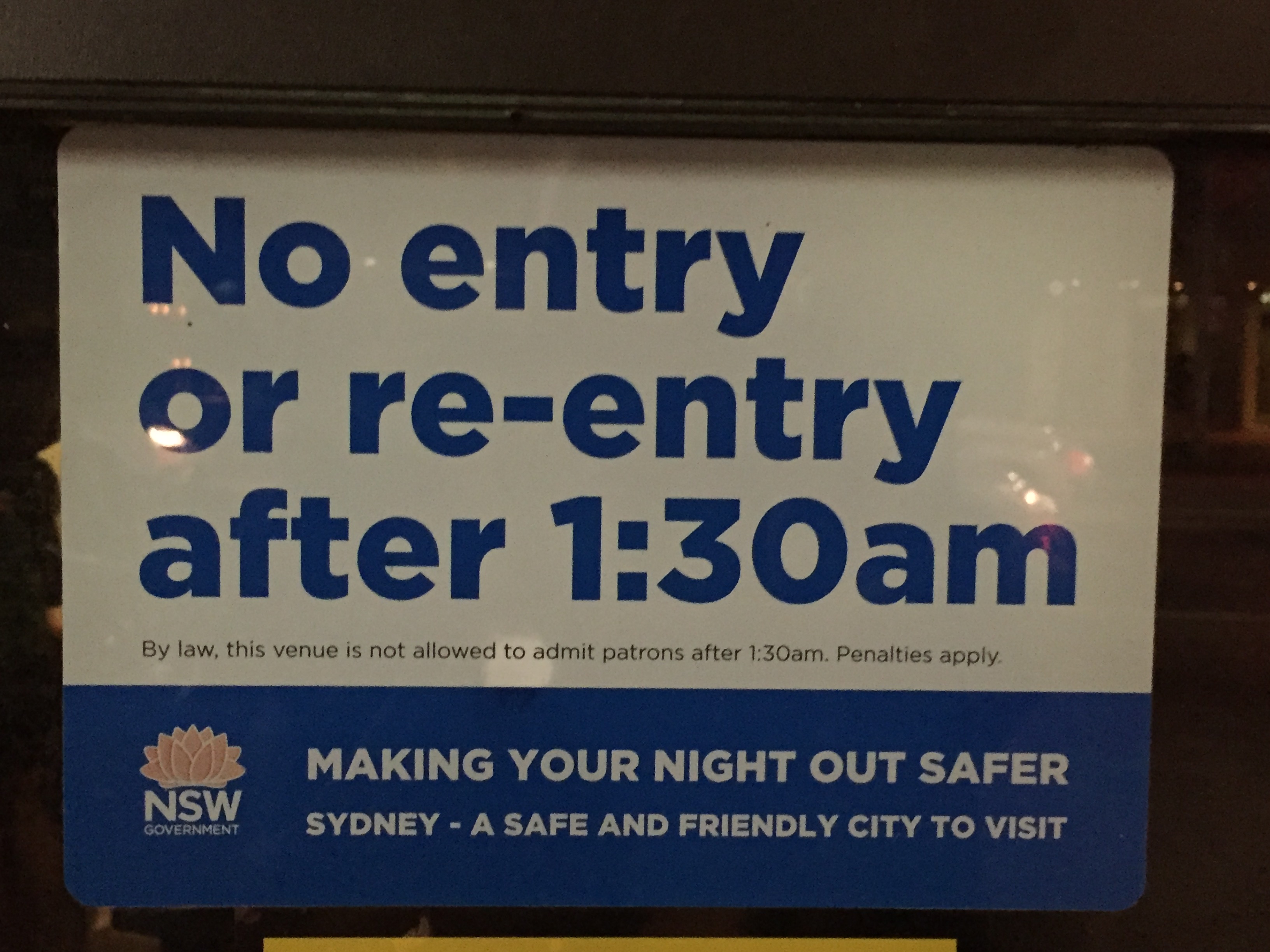

The reality is that morality and government actors have long pressured against urban nightlife and club culture. In Sydney, Australia, as one clear example, the current right wing government has installed a range of “lockout laws” to combat what it sees as nightlife fueled violence in its central business district. The lockout laws are simple: in the central business district, where a majority of the clubs are, no one can enter a venue after 1:30 am and alcohol is not served past 3am, though you can stay on until 5am.

The laws are killing the local night time economy and led to a massive Keep Sydney Open march and demonstration that I attended on February 21. At the rally, local venue owners, musicians and party people spoke openly against the puritanical anti-club laws and about the value of the club scene. The Government sees clubs as hotbeds of drugs, sex and violence, but for the folks gathered there that day, nightlife was about creative expression and creative community.

To punch up the link between pleasure and morals, many attendees at the rally dressed like Puritans.

Pleasure reminds us of our humanity. It’s proof that not only are we in a body but that we are also a body, with feelings, drives and desires that fall outside of what’s prescribed to us. It’s also a reminder that we are not machines. Marxist critics Adorno and Horkheimer believed that the only reason culture has entertainment is to distract us from the fact that we have to go to work again in a few more hours. It’s a pessimistic viewpoint, but I actually think they’re right. That’s why part of the magic and pleasure of nightlife is how it goes against the capitalist impulse to work and be productive.

MADISON MOORE