It was hot and sweaty and we were swathed in fabric. Big bias-cut skirts in bold and bright checks. Barefoot, barely pausing to gulp down water, we danced to the beat of the gwo-ka drums. While Christian marked the rhythm for us dances on his gwo-ka (the ‘big drum’), Ralph’s sounded out the intricacies of the toumblak, or the Guadeloupean rhythm of joy. Ten women dancing the toumblak in madras fabric: it could have been in Guadeloupe, but no– we were in a studio in East London on an unusually warm English summer’s day. One more example of how dance collapses time and place through the trans-corporality of the body.

This Saturday, Francesca and I attended a masterclass by Zil’oKA, a London-based percussion and dance organisation that focuses on the rhythms, songs, and movements of the French West Indies- the islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe. At the end of May, we had enjoyed their tremendous performance at a day dedicated to the French Caribbean at the Hoxton Arches. Ever since then, we had been waiting for an opportunity to hang out with and learn from Zil’oKA. Excitement mounted when we were informed by email of their plans for their masterclass in toumblak, one of the seven rhythms current in Guadeloupean rhythm repertoire.

‘What is a masterclass?’ A friend asked me that evening. I guess in the context of dance, it indicates a few focused hours of accelerated learning, which pushes the pedagogic envelope because a higher level of dance experience is assumed. My dance-learning capacities have certainly improved over the years that I’ve been dipping into Afro-diasporic movement worlds: could I have imagined, even a few years ago, walking into a dance class, learning the basic steps of a new form, and ending up with a mini-choreography at the end of three hours!!! Yet that is exactly what we accomplished together on Saturday! Hooray for great teaching!

My body recognised steps from other Afro-diasporic traditions: for instance, the umbigada (belly-button-bumping), which was such a talking point for Lusophone colonial authorities, gave rise to the Angolan social dance semba (from the Kimbundu word ‘massemba’, or the touching of navels) and, on the other side of the Atlantic, the Brazilian samba…. So amazing to see it reappear as the Guadeloupean piting bo!! A jump, kick and back-cross reminded us again of carnival samba. A four-step move with an accentuated hip thrust recalled both Dominican bachata and Colombian cumbia. It was delicious to sense the echo of a Cuban three-step move in one of the tri-page basic steps.

For me, it was so exciting finally to do a class in the rhythms of the French Caribbean. I have long enjoyed a range of music from these islands—from the oldest creolized Biguine songs (I adore most of all Leona Gabriel, diva songstress from Cayenne), to the funky world music sound of Kassav’, as well as the cerebral experiments of Malavoi and the return to the islands’ roots music, chouval-bwa, by Dédé Saint-Prix. These are on-going dialogues with the rhythms of the gwo-ka, which, like creole drumming through the Caribbean, continues to be a flashpoint of debates around policing, identity, and reclaiming of tradition.

Kassav’ at the Zenith, Paris, in June 2013 (Ananya was at this concert!)

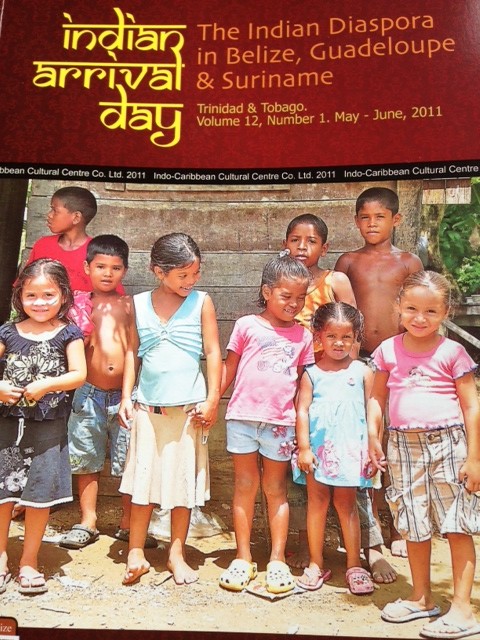

With my apprenticeship in this musical tradition, I wasn’t too slow in picking up the names of the steps and even some creole phrases that we had to chant with attitude during the choreography! – So much so that Zil’oKA members asked me if I actually spoke Creole! But it’s not only sounds and rhythms that had begun to enter my world in the past ten years that I discovered: there were unmistakeable traces of Indian dance movements in some of the basic steps. Rita Lencrerot of Zil’oKA did not find this surprising. ‘Our islands are full of Indian people’, she reminded me. Yes! Another step forward in Modern Moves’ excavation of hidden histories across the oceans….

Of course a material reminder of these entangled transoceanic histories is the madras fabric, which finds its way into the folkoric costumes of almost all the smaller islands of the Caribbean, starting with the Francophone ones. And where there is folkore, there is dance… As the name indicates, these striking checked fabrics were woven in Madras and shipped to the Caribbean through imperial trading routes. Till today, in the era of post-slavery, post-indenture, and postcolonialism, they are produced in South India and exported to the islands- as a new exhibition by the Costume Institute of The African Diaspora will soon demonstrate in glorious detail.

When I was growing up in India, the story of Indian diasporas on sugar plantations were a completely sealed off corridor of history. Noone went down those corridors. Despite some welcome new ways of talking about those old Indian diasporas today, there is still very little out there about the Indian populations in Francophone islands like Guadeloupe, and nothing at all about how Indian and African populations creolized each other in the realms of music, dance, language and food. It meant something indescribable to me when a student of Indian origin from Guadeloupe presented me recently with a swathe of madras fabric to make into a sari—watch this space for the transformation!

For me, dancing in a Madras skirt on a hot London day, marking the toumblak, the rhythm of joy, was an act of performing and reclaiming a supressed history of displacement, survival and encounter. As we moved in unison, and performed the piting bo to each other and the drummers, giving and taking energy, the heaviness of the fabric (which was for me also the heaviness of history) transformed into something that gave the body velocity and grace when we moved. As I spun around, knelt down, struck the floor thrice, I noted with pleasure how my skirt settled around me- when I sprung up, flicking my skirt just so, I felt feminine and powerful. Who said skirts couldn’t be serious??? And that long skirts couldn’t be fun?! Here’s to making and remaking history with a long skirt and a drum!

**Feature Image Courtesy of Francesca Negro**

ANANYA JAHANARA KABIR