On October 24th 2017, half of the Modern Moves team travelled to the U.S. for a month long research trip through the sounds, textures and aesthetics of black street dance cultures and its environs. We set out with an eye towards J-Setting, hip-hop, queerness and other urban styles. With stops in New York, New Orleans, Jackson, Mississippi, Los Angeles and Atlanta in that order, and combining traditional archival research with observation and interviews, the goal of the trip is to think through ways black street dances, fashions and aesthetics emerge and circulate – while tasting all the local foods in the process. In what ways are black creativity, ingenuity and imagination linked to questions of duress? How has black innovation been co-opted by capitalist-imperialist structures, and in what ways can black genius be experienced and conceived beyond harmful colonialist stereotypes that have always had the goal of naturalizing differences between the races?

The first stop on the trip was a pump through New York City and several important archives centered on questions of blacknesss. At the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, we delved through the Hip Hop archive of Steven Hager, an important New York impresario, writer, and cultural critic who is largely credited with “introducing” hip-hop cultures, dances and styles to a broad, mainstream audience. In 1984 Hager developed Beat Street, a Harry Belafonte-produced film that offered one of the first inside looks at the culture of hip-hop. Perhaps one of the most interesting if problematic aspects of his collection at the Schomburg was the way in which he is framed (or, actually, frames himself) as the expert on hip-hop. As one of the first hip-hop journalists, Hager is said to have brought conversations about hip-hop and break-dancing to the mainstream. But white folks are so often credited with “discovering” black creative cultures – straight up Columbusing.

The Steven Hager Hip-Hop Archive at the Schomburg Center contains intricate details of the publication of Hager’s seminal Hip-Hop: The Illustrated History of Break-Dancing, Rap Music and Graffiti (1984), and the records show notes, comments, and ephemera connected to the why and rise of hip-hop culture. As Hager describes in his book proposal, at the time hop-hop was “a movement that started in the working class and was so dynamic and vital, it pushed it’s way across the country and around the world.” Reading this I was surprised and annoyed, as if working class folks don’t already carry the burden of creative innovation and imagination in global popular culture, and as if working class folks are so hemmed in and imprisoned by capitalist structures that they can’t bare to be creative or imagine other ways of being in the world. Indeed, one of the central theories that grounds our research excursion is Black Marxism, a concept spearheaded by Cedric Robinson in a book of the same title and further developed by critics like Greg Tate, Robin D.G. Kelley and Daphne Brooks – a set of theories that recognizes black political struggle at the same time it creates space for black innovation and imagination.

As interesting as the Steven Hager archive was, particularly with regards to the juicy publication details of Hip-Hop – the proposed advance of $30,000-$80,000 in the mid 1980s…just how much of that went back into the community? – we found the commercial aspect of his interest in the spread of hip hop somewhat unsettling. A good deal of the archive had to do with sales figures and marketing – how popular hip-hop culture was in New York, how far it had spread internationally, and the fact that Harry Belafonte was involved with Break Beat. So what? Can’t black cultures survive on their own, without white discovery/celebrity narratives?

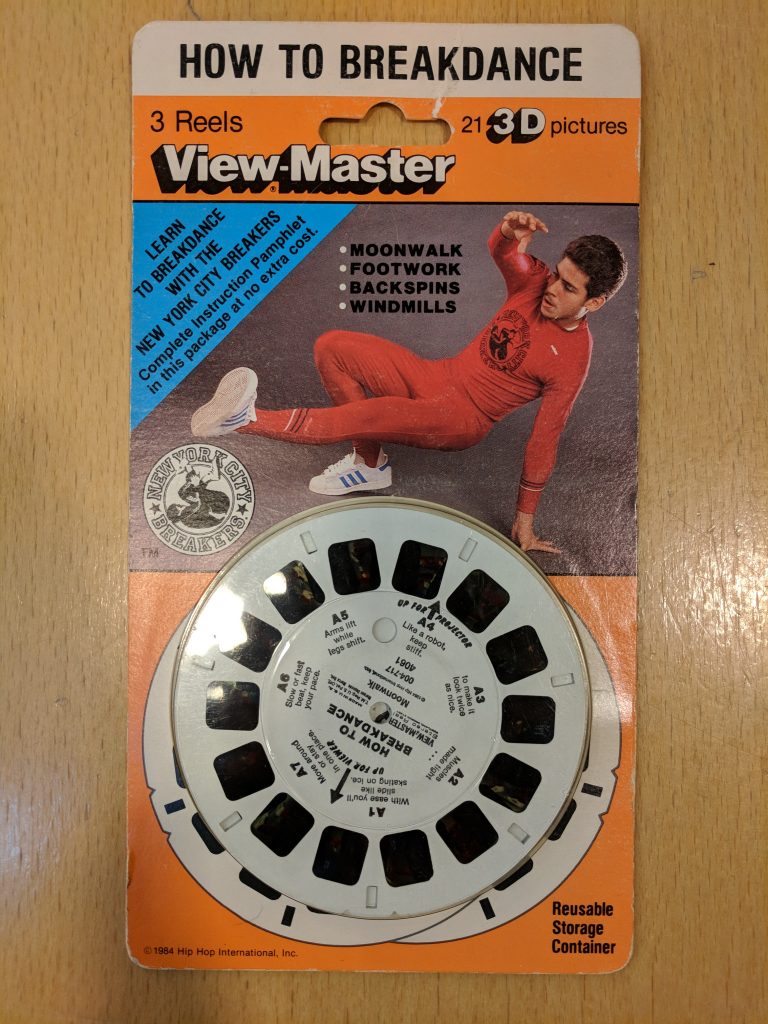

A far more interesting archive was the Michael Holman Collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, the Library’s first hip-hop archive. Holmam, an important figure in the hip-hop, break dancing and downtown music scenes, wrote the screenplay for the 1996 film Basquiat and was a member of the experimental noise band Gray, co-created by Basquiat. The Holman archive is massive and there wasn’t enough time to scroll through every item, but I can say with confidence that my favorite thing from the collection was the “How to Break Dance” view finder. In the 1908s the view finder was a visually immersive device that, before iPhones and Facebook, allowed you to scroll through a cultural scene and really imagine yourself there. You placed the view finder over your eyes – like binoculars – and you inserted a thematic circular “disk” anchored by a wheel of tiny photos enlarged only by the view finder. Scroll through and the action appears to happen before your eyes, right then and there. The archivist was extremely strict that I could in no way, at all, whatsoever open the package of “disks” in order to pop them into the view finder, so I had to imagine the scenario. “How to Break Dance,” the package of disks reads, and as I looked at the pictures I imagined what the moves and choreography would be.

One thing I bookmarked for future research was Holman’s band Gray, an experimental industrial/noise/sound/punk band that straddled the boundaries between the art world and the music world, traipsing between sound, art, visuals, aesthetics and the sensorial. I am always interested in lost histories of black music, particularly with regard to punk, techno, goth, and noise, and there was a great deal of material related to Gray’s staging, performances, cueing, and track-listing that I would be keen to dive through and engage with as part of a separate project. But for now, it was delicious to go through these archives and to know this material exists.

No research trip on dance and nightlife would be complete without a pump to the club, so we ventured to Brooklyn to a warehouse party and danced until nearly 7am. In the process we thought a lot about music, soundscapes, sound, space and blackness – or lack of blackness. What does it mean, for instance, for DJs to perform black/queer music to a sea of white bodies, particularly in a Trump-led America? How do white bodies connect to the ghosts of black creativity on the dance floor? It’s no secret: part of my personal interest in this topic is to take electronic musics back from white audiences, to re-center black and brown bodies in the process. Reclaim the BPM.

From New York our travels led us to New Orleans, Louisiana where we found a Second Line and dropped into the Backstreet Cultural Museum. Leyneuf made her way to the Amistad Research Center by way of the New Orleans street car, which was quite a ride in the sense that the areas through which the street car went were of course former plantation owner houses and had a grand but morbid presence to their architecture, an incredibly haunted presence. At Amistad, she tried to find specific work on second line. What she did stumble upon was the Second Line Journal which however was more about jazz manifestation in New Orleans throughout the 50s and 60s as opposed to the second line dance form. She moved on in terms of hip hop research and found fabulous hip hop comic books documenting the history of hip hop in a sci-fi type of aesthetic called Hip Hop Family Tree – Fantagraphics Comics on the History of Hip Hop Vol 1-3. Of course, on her way back to the French Quarter from the the university, she went to the Chilli Museum where she must have tried 50 different chilli sauces, bottles marketed from goth to vodou to creole aesthetics. Of course it wasn’t the only time she went – she had to go back.

Continuing our travels through the deep south, we trained-it to Jackson, Mississippi – by all means the highlight of the trip — where we attended the homecoming festivities of Jackson State University, an historically black college. We went to the football game, waited for a Step Show, saw the homecoming parade and ate some good old Mississippi bar-be-que. Jackson was the highlight of the trip because it was cold hard evidence of black joy, ingenuity and creativity — it was a celebration of blackness.

In Los Angeles, we primarily visited the Cheryl Keyes archive at UCLA where we listened through her interviews with early hip hop pioneers — everybody from Russell Simmons to Queen Latifah. Afterwards we decided to have a walk along Sunset Blvd, of course, and get a taste of the feels on the way checking out the bookstore Booksoup, stopping for mexican at Pinches Tacos on Sunset blvd and speculating on the overall aesthetics of LA architecture. Following that we went to the fabulous Underground Museum, launched by Noah Davis, Kahlil Joseph’s recent brother’s community project curated by Joseph and his wife Onye Anyanwu, both of whom worked on Beyonce’s Lemonade. The exhibition: Artists of Color, was a phenomenal immersion in experience through color and the senses and had an immense despite quiet insertion into the skin of experience. We spent significant time in the bookstore after the exhibition, had a chat with the museum staff and became enthralled with their literary collection. Of course, they seem to host the most phenomenal and upcoming black thinkers and artists whilst the museum itself having a seemingly different performative aspect to it’s integration in the predominantly black and latino community of the neighborhood. When we spoke to the museum staff, they articulated that the whole point of the Underground Museum was to bring high quality art to disadvantaged communities.

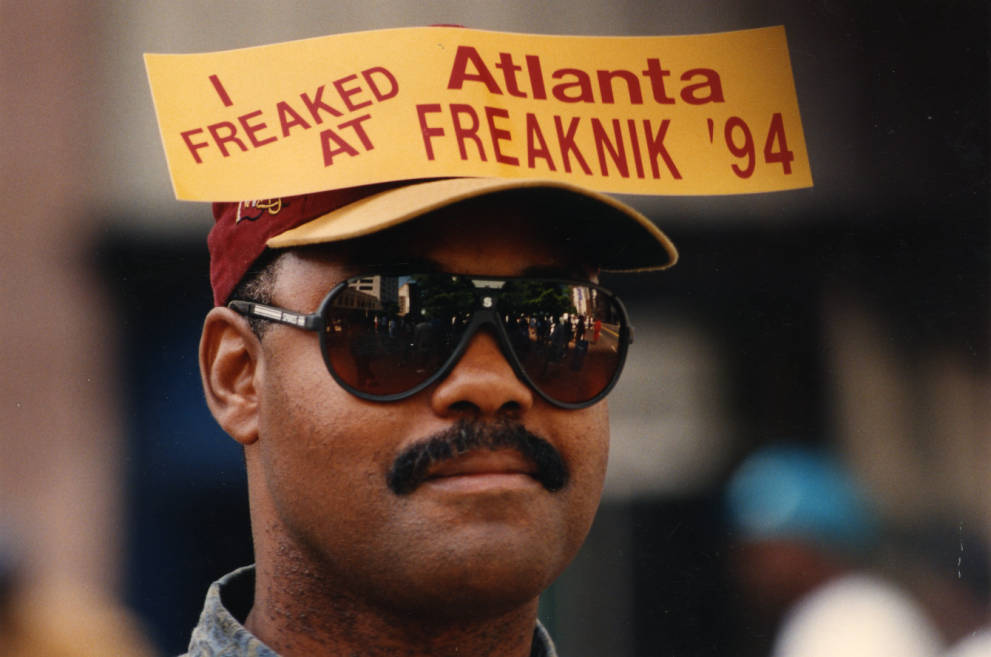

For the last leg of the trip, we headed to Atlanta specifically to find out about Freaknik, a black spring break party that was the pinnacle of black expression in the 80s and 90s but which was vigorously shut down and policed by the City, who felt it conveyed the wrong image of a city that was about to host the 1996 Olympics.

The central question that framed our trip had to do with how black expressive traditions allow us to think through the tensions, pressures and contingencies of living while black. One term that grounds this work is Lauren McLeod Cramer’s vision of “liquid blackness,” where “liquid blackness” means the excess of codes that constrict the movements of black bodies in space, as well as the possibility of reprogramming the racial order. “Liquid blackness” expresses the aesthetic and political possibilities available when blackness is understood not as a locatable, definitive set of codes but as an expansive force, not only in scholarship but in praxis.

The value of this trip lay in the fruitful conversations we had about aesthetics, blackness, and performance — in the archives, on the street and with taxi drivers. But it was also about the rare opportunities we had to visit archives and areas of the country we would likely have not made it to under other circumstances.

Leyneuf Tines and madison moore