Prelude: ‘Paris is about life’

On the 14th of November 2015, I was at the Eurostar check-in at the Gare du Nord, Paris, scrolling through my Facebook newsfeed. A quote from the French Cartoonist Joann Sfar, (who in fact works for Charlie Hebdo) reposted by a Parisian friend, caught my eye: ‘Friends from the whole world! Thank you for #PrayforParis, but we don’t need more religion! Our faith goes to music! Kisses! Life! Champagne and Joy! #Parisisaboutlife’. As it so happens, I was carrying with me back to London my dancing shoes and a bottle of champagne gifted to me by one of the nicest people I know in Paris. The previous night, I had had dinner with some members of the Modern Moves team and friends. Two of us had been out for Kizomba research just the night before (the 12th November) at the club Khao Suay in the heart of the Bastille. The only reason we were not all back there on the 13th November is because we were recovering from the excellent conference ‘Orchestrating the Nation: Music, Dance, and Transnationalisms’.

photo taken from Facebook.

Professor Ulrike Meinhof from the University of Southampton had closed the conference with the remark that while the whole world was antagonised and divided, through music and dance human beings continued to connect with each other. However, even as we were celebrating this sentiment and our successful conference in one part of Paris, in another part, carnage and bloodshed was unfolding around the Bastille where we might have been dancing. The attacks were aimed at decimating people who were engaged in convivial and modern leisure pursuits typical of the concept of ‘Friday night’ in a city both global and intensely local: enjoying themselves at bars and restaurants, enjoying a sports spectacle, and enjoying a music concert at a venerable Paris venue, the Bataclan.

Since only coincidence and tiredness had prevented me from being right in the scene of action, I couldn’t help thinking of Khao Suay, the restaurant in the Rue du Lappe, Bastille, whose basement has been serving Paris’s kizomba dancers for quite a few years now. What would I have experienced had I actually found myself at Khao Suay that night? Through Facebook I pieced together the story. It seems that, as the terrifying drama unfolded with little clarity on the doorstep of the club, the owner of Khao Suay, Henri Lee, had the presence of mind to issue an all-night lockdown. Apparently, a club full of kizomba lovers danced the night away in each other’s arms, as the DJs played on. Henri Lee’s role was recollected in several posts as one of paterfamilias, saviour, and comforter, creating a temporary safe haven in the middle of mayhem and danger, even opening his kitchens at 3 am to serve chicken and French fries to the famished and frightened crowd.

I contacted Henri Lee (whom I didn’t know yet personally) on Facebook to ask him for his words. He graciously replied that he didn’t like to talk much about himself, and directed me to the same Facebook post that had caught my eye. Since the privacy of that post had been set to ‘public’, I reproduce a translation of it below:

‘Impossible to fall asleep… All this is a nightmare! Thousands of cops, firemen in the streets of such a deserted Bastille (although usually so lively on Friday evenings), thousands of sirens that we hear all over the place and all the people bursting into tears in the streets!!! One always thinks that this will happen to others yet this time it happened here. This is terror!!! I have to thank Henri Khao Suay Lee!!! Who kept us safe in his establishment and who took good care of all of us!! Opening the kitchen at 3 in the morning to offer chicken and frites to everyone, keeping us updated of what was happening and handling everything for the best, not everybody would have done so!!!! Huge hugs for the victims, their families and relatives!! I have no words.’

Having studied trauma for many years, I found it easy to detect its signs in this as well as other Facebook posts attesting to that evening at Khao Suay. All commentators remembered the poulet-frites, some even posting photos of the chicken ready to be consumed. The deep connection between food and social dance has been reiterated in Modern Moves events and investigations. Here, the food that arrived like manna from heaven was functioning by association to recall another activity involving shared enjoyment of sensation, and collective proof of the body’s vitality: dancing kizomba.

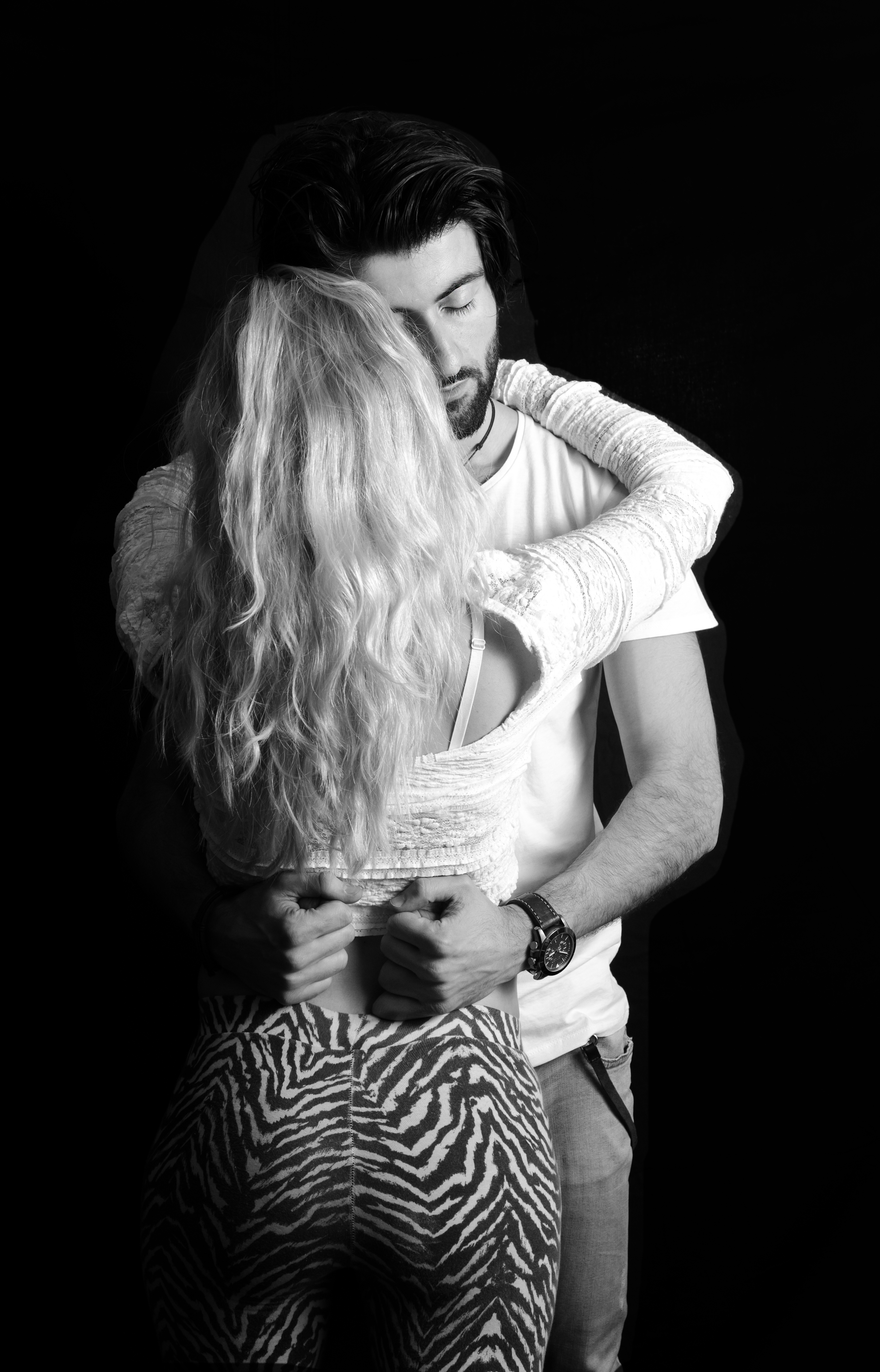

Once again the ‘kizomba hug’ came to rescue human beings caught in a web of violence and uncertainty, when the rhythms of the music induced a sense of order and calm within the space of the dance while chaos and curfew ruled outside. I say ‘once again’, because it was in similar conditions, during Angola under civil war, that the steps of the social dance we now call ‘kizomba’ were forged out of older dances. Stories of dancing until curfew was lifted, of talking, joking, and singing when the electricity disappeared for hours, are now part of kizomba lore.

My close brush with the ISIS attacks on Paris through kizomba at Khao Suay made me remember that parallel. More than ever, it impelled me to articulate some of my evolving ideas on war and peace and kizomba. I have noted in particular the warmth with which kizomba has been adopted in certain European countries which seem to have no shared history with Angola or any other part of continental Africa—either that of colonization or cultural exchange– those arising from the former Yugoslavia, the Baltic nations, Sweden, Hungary….

photo taken from the BKC Facebook page.

The propensity of people from these countries to embrace kizomba intrigues me and I’m searching for an answer through a combination of methodologies: through alternative frameworks for explaining cultural connections– most importantly, the Cold War, in which Cubans, together with their music and dance, moved between Europe and Africa— and a ‘psychosocial’ approach to society, where I read symptoms of collective traumas of different kinds together with ‘responses’ or ‘solutions’ (in this case, couple dance with African origins). The bigger question remains the basic Modern Moves one—why do people, often with no connection to Africa, turn to dances of African heritage for leisure, pleasure, or healing?

In my search for answers, I have found extremely important the life stories of individuals in the world of dance. So in this Moving Story, I present three individuals with no ‘personal’ or ‘ancestral’ connection to Africa, whose love for kizomba developed in cities far from the African continent, and with small or non-existent African diasporas. The subjects of each story are very different from each other, but they also share many things—most importantly their practice of kizomba, and the generosity and trust to open up their innermost selves to a stranger (me). I like to think that these two factors are connected.

Read on!

1) Ljubljana: ‘We feel it’

Urska Merljak met me at the foot of the statue of France Preseren in the centre of Ljubljana. It was a sunny Sunday in January 2015. She sat waiting for me, holding a magazine, the Slovenian equivalent of The Big Issue. On my arrival, she showed me the word ‘Urska’ heading an article on the first page. It seemed some kind of sign: one of the things I’d asked earlier was the meaning of her name. I joined her at Preseren’s feet as she started telling me about his famous poem about Urska, a young girl from Ljubljana, who loved to dance.

One day, a river god rose from the waters of the Ljubljanica—which was flowing right by us under the city’s famed Triple Bridge. He joined her in the dance and spirited her away from the city to the waters. ‘A black cloud appeared and when it disappeared, so did they. No one saw Urska again.’ We contemplated these (non) coincidences: the poem (which is about couple dance as practiced traditionally in Central Europe), the protagonist and her namesake, and our convergence at the poet’s statue. She pointed to me a house across the street. ‘That’s the balcony under which Preseren used to serenade his Juliet’.

Clouds, unspecified demons, and the romance of connection were everywhere in the conversation we had about why kizomba is meaningful to her. If intuition is a sixth sense, then to dance kizomba is to invoke the sensual part of ourselves as a seventh sense to be discovered. Hugging each other [which kizomba necessitates] leads to a connection of two souls. Indeed, each soul is a fragment of a larger whole, waiting to be united with each other. ‘We are stuck’; kizomba allows us to be unstuck, to unblock ourselves. The proximity it demands to a member of the opposite sex both releases ‘sexual energy’ and requires its reorientation towards ‘sensual energy.’ ‘People don’t think about [these energies] but they feel it. It’s up to them what they will do with the feeling.’

Despite having a lovely Friday evening in the Kizomba room at the Magic Salsa Festival, which included meeting new people, talking to Kwenda Lima, and dancing hours of kizomba at the opening party, Urska had woken up that morning with ‘a feeling of overwhelming loneliness. We have our demons— we have to embrace them.’ Kizomba does this to us— it releases inexplicable feelings, and increases our vulnerability. ‘We are sometimes afraid of being hurt.’ At the same time, ‘we are starving to get some meaning into our lives—we are not just a body, we are a soul—indeed, a grand unified soul. When we relax our bodies in dance, embrace another body that is vibrating on the same level as us, this is so natural and divine at the same time. We need each other to awaken the parts of each other.’

We were by now sitting outdoors at a café on the banks of the river. The rays of the setting sun illuminated the scene and the church bells started ringing– a fitting son et lumiere show for our discussion on the natural and the divine—but also a reminder of the different temporalities, sacred and secular, which punctuate and order human lives in the past as well as the present. The streak of anti-rationality with which Urska started our conversation, returns. ‘Maybe there is no point in knowing everything. We have to allow ourselves to feel it.’ Sensual energy can heal us and make us stronger. At the moment, we are easy to lead: ‘they are leading us. If we become strong, we will destroy the system.’

We were by now sitting outdoors at a café on the banks of the river. The rays of the setting sun illuminated the scene and the church bells started ringing– a fitting son et lumiere show for our discussion on the natural and the divine—but also a reminder of the different temporalities, sacred and secular, which punctuate and order human lives in the past as well as the present. The streak of anti-rationality with which Urska started our conversation, returns. ‘Maybe there is no point in knowing everything. We have to allow ourselves to feel it.’ Sensual energy can heal us and make us stronger. At the moment, we are easy to lead: ‘they are leading us. If we become strong, we will destroy the system.’

As I had also encountered this mysterious ‘they’, and the ubiquitous ‘system’ in my discussion the previous day with Kwenda Lima himself, I felt compelled to stop Urska and ask: ‘who is the ‘they’? What is this ‘system’? Her response was quite clear. ‘The leaders.’ Visions of Tito and other strong leaders of the socialist era floated up in my memory. Are these socialist leaders or capitalist leaders, I asked. ‘These are those with money and ego. It’s a problem of all humans, not of socialism or capitalism per se.’ Yet a reassessment of life under socialist Yugoslavia and capitalist Slovenia shows this problem to be exacerbated in the capitalist present.

As I had also encountered this mysterious ‘they’, and the ubiquitous ‘system’ in my discussion the previous day with Kwenda Lima himself, I felt compelled to stop Urska and ask: ‘who is the ‘they’? What is this ‘system’? Her response was quite clear. ‘The leaders.’ Visions of Tito and other strong leaders of the socialist era floated up in my memory. Are these socialist leaders or capitalist leaders, I asked. ‘These are those with money and ego. It’s a problem of all humans, not of socialism or capitalism per se.’ Yet a reassessment of life under socialist Yugoslavia and capitalist Slovenia shows this problem to be exacerbated in the capitalist present.

Urska went on to elaborate. ‘I was seven years old when the system changed. I remember the feeling I had then. We were more connected then [emphasis mine]. My parents were building a house and the whole village helped them. Nowadays, it’s all about paying each other to help each other. Then, people were together in the streets. Now, we are in the house. This is individualism. Its not about the country that we live in, or the nation that we are, we are all the same,’ she reads out from her notebook. ‘But in today’s Western world of capitalism and individualism, money and ego power, we are more and more disconnected with each other and ourselves.’

We need to find our souls to get over the ego, and it is here that kizomba can help. But this power of kizomba lies not merely in the dance as a formal activity: it is intimately linked to Urska’s awareness of kizomba’s African affiliations. ‘I feel Africa and people coming from that continent have a socialist impulse, transmitted through the generations. They live differently in relation to their environment.’ Even if this is a romantic fantasy, the feeling of ‘Africa’ transmitted through kizomba serves as solace and utopian hope to this citizen of the former ‘Yugosphere’.

2. From Belgrade to Tallinn: Feeling Africa

Nemanja Sonero is a kizomba dancer and teacher living in Tallinn, Estonia. I met him online on the many Facebook forums in which the origins, evolution, meaning, and music of kizomba are hotly debated. He and I were usually in agreement. We became friends, exchanging ideas through private messages, only meeting face to face at the first iKiz Kizomba Festival he organised— extremely successfully— at Tallinn this November. A tall Serbian man in a dashiki and retro glasses, he cut a striking figure. While dancing he was gentle and fun, able to close the ‘height gap’ between us with ease, and this was his attitude during conversation and interaction.

In his choreography with his dance partner, Laura, we saw a Finn and a Serbian, who met in Finland, dressed in ‘Afro-Tribal’ mode, dancing expertly and with passion Angolan semba (the precursor of kizomba, which has developed both in step with and independent of kizomba), enlivened with touches from belly dance (Laura is also an expert belly dance artiste). How did a Serbian come to ‘feel Africa’ while dancing in Tallinn? Nemanja and I finally found the time to have a morning coffee ‘together’ where we discussed his story through Facebook messenger.

In his choreography with his dance partner, Laura, we saw a Finn and a Serbian, who met in Finland, dressed in ‘Afro-Tribal’ mode, dancing expertly and with passion Angolan semba (the precursor of kizomba, which has developed both in step with and independent of kizomba), enlivened with touches from belly dance (Laura is also an expert belly dance artiste). How did a Serbian come to ‘feel Africa’ while dancing in Tallinn? Nemanja and I finally found the time to have a morning coffee ‘together’ where we discussed his story through Facebook messenger.

The trigger for this conversation was a comment he had made ages ago to me— ‘we were dancing in the streets when there were bombs exploding all around us.’ In my understanding of the Bosnian War and its aftermath (the NATO bombing of Belgrade which was the crisis Nemanja had referred to) I had never spared a thought for the Serbian, who was equated in my mind with ‘perpetrator’ status. Here was my first contact with a Serbian who was far from the images I had held, and whose memories of the NATO bombing were connected closely with his memories of dance. Apart from dancing kizomba, Nemanja spoke English, Spanish, Portuguese, some Estonian and Russian, and his native Serbian…. Where in the story of a war-torn adolescence was there place for all this cosmopolitanism?

Let us imagine, in Belgrade in the late 1990s, a bored, hyperactive and highly intelligent high school kid, trapped between a difficult home life and an educational system that responds to abnormal social conditions by regimenting its students even more than is normal for school. As Nemanja recalls, ‘I just didn’t find school interesting, the whole system of repeating like a parrot.’ In his neighbourhood are young boys slipping into drugs and other criminal activities. Our protagonist’s brother, sensing this fate as a real possibility, introduces him to— capoeira.

Belgrade in the midst of the disintegrating Balkans, offering its youngsters capoeira: how come? It so happened that a British capoeirista was in Belgrade at that time, teaching capoeira for free in the ‘Angola’ style in a house for homeless and destitute children, including those of Roma stock. As with slaves on the sugar Plantation, where capoeira first developed as a means of resistance and physical and spiritual training under difficult conditions, so in the urban dystopia of Belgrade in 1998: capoeira was serving as an ad hoc social glue.

The young Nemanja, who was already skating, skateboarding, climbing trees, and listening to hip-hop, finally found in capoeira something challenging, fun, and new. ‘Capoeira gave me something to focus on, so I would not go to school, but go train.’ With his British teacher, he also practiced English, which he had already absorbed like a sponge through subtitled television programmes. In time, capoeira also opened the door to Portuguese, a language that he lives and breathes now as part of the Lusophone world of kizomba. When, because of the war, the teacher was forced to leave, it was Nemanja who took over his classes.

Again, as on the Plantation, so in Belgrade: from capoeira to couple dance was the next step. At that time, one of his female students took him to a Cuban bar, where he encountered Choma, a Cuban graphic designer who was offering Cuban style salsa classes. Nemanja was soon picking up Spanish as well, and learning about the orishas and Afro-Cuban percussive spirituality. The Cold War had ensured that there had been plenty of Cubans in communist Yugoslavia. They didn’t need a visa, Nemanja recalls. What is rather surreal nevertheless is the image of a Cuban holding salsa classes in a bar while Serbia was grappling with all kinds of social, economic and political effects of coming out of long war. The video below gives a general idea of the continuing popularity, in Belgrade, of the Cuban style of dancing salsa:

On the streets, in the meanwhile, people were selling pirated music on cassettes and later CDs. From these sellers and his friends, Nemanja expanded his music education, listening to reggae, Cuban music, what we call ‘world music’ in general, and even Angolan semba. His brother being an amateur computer enthusiast, they always had Internet at home, so, like Neo in the Matrix films, Nemanja reached out to the world through those early retro computers. He became ‘friends’ with Brazilians and African Americans online, journalists and teachers, who ‘helped me understand many things’: ‘the history of capoeira’, ‘reggae history, and Ethiopia, and slavery.’

Through ‘guerilla’ methods of accessing the wider world, this young man in Serbia was learning about the deeper histories of slavery and colonialism that connected the different kinetic and performative practices that he was increasingly drawn to. From his scattergun exposure to capoeira, reggae, hip-hop, percussion, salsa, the orishas arose a desire to join the dots through accessing information as well as physical expertise. Was he at all aware that all these forms were linked to the history of slavery and Black culture?

‘Not as I do now’, Nemanja reflected, ‘but very much, yes. And I always had a thing for folk traditional dances from Latin America and Africa… I always felt comfortable falling into that feeling of a trance or expressing myself with it.’ The next step then was to embrace kizomba. Already in the mid 2000s, friends in the Angolan embassy were lending him CDs and videos of semba music, while some of his dance friends were being exposed to the dance kizomba, during travels to Portugal. In the late 2000s, he invited a white Portuguese teacher of kizomba, Benjamin Nande, to the Serbian Salsa Congress, which he was organizing.

By the time Nemanja received his first invitation to teach salsa at the Vilnius Salsa Congress in 2008, kizomba was already in his dance repertoire. That first trip to Vilnius led to Nemanja’s eventual relocation to another Baltic country. ‘Somehow destiny and events took me to Estonia in the end. I liked it here, because it was calm and nice and no stress.’ Although a dance polyglot who ‘loved dance so much and the possibilities’ that he ‘wanted it all’, he realized that the life of a dance professional in Europe necessitated a self-presentation as a specialist of some kind.

Kizomba makes Nemanja ‘feel very comfortable and relaxed’. Teaching first at salsa festivals and events which had scope for kizomba, and then at exclusively kizomba events, while building up the kizomba scene in Estonia (culminating in the organization of his own kizomba festival in Tallinn this year), Nemanja is clear about what kizomba allows him to feel: ‘I love to feel my partner… to get close to my partner, and kizomba and tango give me that, and I feel this is what I need more.

But I will always do different dances, and always learn something new, that will never stop no matter what I do.’

True to his word, Nemanja is now dedicating himself to pole dancing. While it is probably impossible to establish an African-heritage basis to pole dancing, we can nevertheless see how the Black Atlantic expressive arts have been crucial for a young boy from the war-torn Balkans to become a cosmopolitan man of the world. But it is too simplistic to draw stark distinctions between Serbia in the shadow of bombing, the peaceful Baltic region where he now lives, and indeed Angola where kizomba came together as a dance. All these regions were deeply impacted by the Cold War, and the same Cold War produced its own cosmopolitanism in which Serbia, too, participated.

Photo from the iKiz Festival Facebook page.

It is more worthwhile to consider African dance and movement forms as allowing someone like Nemanja to channel back into himself the best of Serbian society— what he remembers as ‘not only its messed-up history and war and violence, but a really wonderful place and people, even in those hard times’. Different kinds of ‘African heritage’ dance passed through his body over time to be assimilated into and to expand his kinetic vocabulary. Their swag, their style, and their very different energies– from the explosiveness of hip-hop to the meditative possibilities of kizomba, have sent him healing messages at different stages of his life.

3. Budapest, Stockholm: Moving into Mindfulness

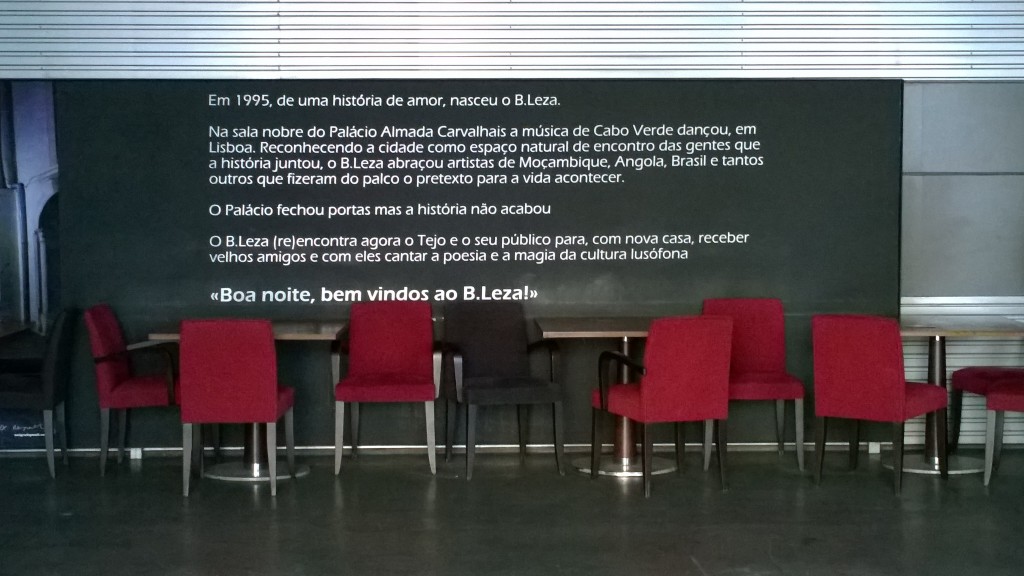

In August 2015, I visited the Budapest Kizomba Connection, a festival now in its fifth year and organized by the superbly capable Nikolett Hamvas, a Hungarian woman who lives in Lisbon, speaks Portuguese, and appreciates Angolan and PALOP culture as her own. This year, the festival took place on the cruise ship ‘Europa’ moored on the Danube. On Saturday night it slowly cruised under the romantic bridges of this grand Central European city. Beautifully lit buildings floated past. Dressed in white, bathed by the full moon, we reconnected to the elements through kizomba. (see this story’s featured image). ‘Africa’ was reconfiguring ‘Europa’.

At BKC I enjoyed reabsorbing the energies of kizomba into my body and mind. I was learning to change the temporality of my enjoyment (of everything) and kizomba was part of the journey. I was content to watch the dancers whose style I appreciated rather than rush to ask them for a dance. This was how I spotted on the dance floor a young man, slender, pale and dark haired in a Mediterranean kind of way, with his name emblazoned down his trouser legs: ‘Ronie Saleh’. His style mesmerized me.

At BKC I enjoyed reabsorbing the energies of kizomba into my body and mind. I was learning to change the temporality of my enjoyment (of everything) and kizomba was part of the journey. I was content to watch the dancers whose style I appreciated rather than rush to ask them for a dance. This was how I spotted on the dance floor a young man, slender, pale and dark haired in a Mediterranean kind of way, with his name emblazoned down his trouser legs: ‘Ronie Saleh’. His style mesmerized me.

This style was not the kizomba that the Angolans and PALOP people first brought to Europe and which is danced alongside the more upbeat, playful style ‘semba’; but neither was it purely one of the newer styles developing from kizomba that have proliferated in France in the past five years, the most recent of which is being called ‘urban kiz’. BKC was a bit of a battleground between the so-called ‘urban kiz’ styles and the so-called ‘traditional kizomba’ styles– in keeping with debates raging through the kizomba world about the meaning, movements, mood, and music that are appropriate to this dance and its developments.

Despite those debates and differences, the same dialectic between war and peace, between violence and its overcoming, that brought forth kizomba, and that we have been exploring through my previous protagonists, also gave rise to a dancer who appears to veer towards urban kiz. In 1990, when he was but a year old, Ronie’s parents escaped the war in Iraq and arrived in Sweden. Growing up in a secular Muslim household, the young boy thrived on the opportunities Sweden offered: theatre, singing, writing music and playing the guitar, and the usual set of Black Atlantic urban dances: hip-hop, breakdance, popping. He performed on stage and regularly won dance and music competitions.

Perhaps it was this confidence that allowed him to overcome something that could have been an impediment in his encounter with the world: the stutter he had as a child, and his long experience with speech therapists. But—in a positive and farsighted move– Ronie decided to ‘work with something that I know myself how it feels,’ eventually obtaining a Masters degree in Speech and Language Pathology. Around the same time, something new entered his life: he started to dance foxtrot and ‘got hooked right away’, because ‘the connection and feeling was amazing.’ An interest in feeling and connection thus underlay both his choice of subject for study and his new dance.

It’s not at all uncommon for dancers in search of connection to switch from the sharp and dexterous moves of Black Atlantic urban dances to couple dances like salsa and kizomba. But I had never come across a narrative in which foxtrot featured as the couple dance of choice. Indeed, I knew little about foxtrot beyond a basic awareness that, like the charleston and lindy hop, it was one of the classic swing dances of New York. When, under Ronie’s guidance, I watched some foxtrot videos, I realized that it has been evolving along lines similar to others from the swing family, most obviously West Coast swing; moreover, the path towards ‘foxtrot nuevo’ and ‘dirty fox’ discernible from the titles of youTube videos recalls parallel developments in tango.

At a foxtrot workshop Ronie attended in November 2013, a kizomba song was played during the break. Drawn to the ‘enchanting’ music, he also responded to a similarity of feeling between foxtrot and kizomba. Foxtrot, Ronie explains, ‘is all about body connection and flow on the surface of the dance floor’. Unlike salsa, and like kizomba and tango, this connection is ensured by upper body contact between partners. Interestingly, one of the divergences between urban kiz and kizomba is the diminishing of that upper body contact. Ronie’s retention of this connection, a direct legacy from foxtrot, alongside footwork developed in Paris rather than Angola, is one of the ingredients of what we started calling (only half in jest), ‘Ronie style’.

To this emphasis on connection, Ronie adds a playfulness he inherits from his love of hip-hop and popping. This tendency is apparent in most visually arresting kizomba dancers—from the Panamanian Albir (one of Ronie’s earliest inspirations), who is renowned for his use of hip-hop moves, to the Angolan Morenasso who, based in Paris from 2010, has been one of the earliest propagators of kizomba and semba internationally and whose dance style flamboyantly draws on the Angolan urban dance kuduro. What stands out as ‘Ronie style’ is the mix of body connection, street dance playfulness, basic steps taken from both the ‘Paris styles’ and kizomba, and, most importantly, meaningful variations of time and energy.

‘I like to make contrast in how I dance with my partners, as you notice in my videos,’ clarifies Ronie; ‘some videos are mainly slow motion and peaceful and others have a lot of attitude and firm moves, playing with time, closeness and space—but I always let connection be the main attribute of my dance style.’ These contrasts are a continuation of syncopation, one of the most resilient and recognizable signifiers of Africanity in music and dance. It is another kinetic inheritance from slavery: syncopation was the slave’s mode to overcome ‘Plantation time’ and tease out alternative temporalities for resistance through the body. Ronie’s ability to slow down to an extreme the tempo of the dance highlights the contrast with faster syncopations.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dMoihM-KRz4

These variations are further enhanced by Ronie’s sensitivity to a deeper difference between foxtrot and kizomba: ‘the feeling and how you walk and put down your steps along the floor. In Kizomba you walk with the energy downward—connection with mother earth. In foxtrot you are more on the surface of the floor.’ ‘It took me a while to get the kizomba movements in my walking (cause I was too much gliding on the floor instead of walking downwards)’, remembers Ronie, ‘and still some foxtrot dancers tells me that they can’t see the difference between my foxtrot and kizomba, but that’s maybe what makes my style bit unique.’ It’s the contrast in energies as much as their coalescence, together with the slowing down of time, which allows him to draw new possibilities out of kizomba.

The overall effect is reminiscent of the body’s mastery over its environment that is the forte of Asian martial arts. Although ‘not religious’, Ronie ‘has been meditating for eight years’, and sees his beliefs as ‘more headed to Buddhism and Mindfulness.’ Like a number of kizomba dancers he has grasped kizomba’s potential to approximate the meditative possibilities that Asian embodied philosophies access and refine. Kwenda Lima’s ‘kaizen dance’ and ‘bodhi kizomba’ has been pioneering in this respect. It is no coincidence that I experienced Kwenda’s unique classes with both Urska and Ronie, who recalls ‘crying with the impact’ of Kwenda’s kaizen workshop on the top of the Europa’s sun deck that blazing hot Budapest afternoon.

Like Kwenda, Ronie synthesizes fragments of the sacred dispersed across the (post)secular world to explicate connection through dance. He turns to the four elements ‘Fire, Water, Air and Earth’ and their attributes: fire’s being ‘firm and sharp movements’; air’s, the ‘flow’; earth’s, the connection created by the body’s downward direction of energy; and water’s, ‘patience’ (‘just imagine how it is to walk in water’, he asks me). This verbalization of a dance style, itself a creolized product with African and European influences, combines ancient Greek philosophy and Asian ideas of energy flow. ‘If we can vary the way our souls move our bodies in accordance with life (the four elements), then we can share a deeper and more three-dimensional experience with our dance partners. The way we dance will not feel like separated steps anymore – all the “Steps” become ONE energy– we`re floating.’

Ronie has been dancing kizomba ‘non-stop’ during the past two years, teaching since August 2014 in Stockholm’s biggest dance school, and, a year later he quit his job as Speech Language Therapist to devote himself full-time to dance. He says with a faint air of disbelief, ‘I’m now travelling all over the world sharing what I love the most, to make this world to a better and happier place.’ Apart from giving weekend workshops and teaching at festivals, he still teaches foxtrot (with a kizomba touch), which now has become really popular in Scandinavia. From Iraq to Stockholm and from Stockholm to all over the world, kizomba and foxtrot and hip-hop and popping comes together in this dancer’s body and mind, to reaffirm the salience of the Black Atlantic as a kinetic philosophy but also reconfigure it as a world resource.

Concluding Speculations

The ways in which different kinetic strands of the Black Atlantic, floating away from each other in the tailwinds of history, unite in his and the other two stories I have told here, move the debate over cultural appropriation of Black expressive forms towards considerations of kinetic sharing and the body’s hospitality towards dance and music traditions that are not ‘meant to be our own’. These stories of individuals from the margins of Europe and beyond, take us to a world beyond the binary of ‘black’ and ‘white’, and make us think harder about who is allowed to take what from whom in the remaking of the self that modernity invariably seems to demand, no matter where we are born and where we grew up.

I started this Moving Story by a recollection of dancing kizomba through the recent attacks in Paris, and I want to return to that scenario by wondering what would have been the conditions under which the young terrorists would have taken up kizomba in the suburbs of Paris, where urban kiz first came together, instead of guns and body explosives. We can’t just point to social marginalisation, religious beliefs, skin colour, and collective trauma as explanations. Some young men and women across Europe have turned to dance to heal, others have not. Trying to work out why (in both cases) means taking far more seriously than ever dances like kizomba and their deeper connection with war, peace, and our global modernity.

All photos by Ananya Kabir unless otherwise specified.

A heartfelt thank you to Urska, Nemanja, and Ronie! Gratitude always to Kwenda Lima for opening the pathways of consciousness. A special merci also to Henri Lee and Domino Ancete.

Thank you to Nemanja and Nikolett for such hospitality at their festivals; Vedrana ‘Dottoressa’ and Darinka Chebella for talking to me about dance and the ‘Yugosphere’ in Ljubljana; to my ‘Kaizen family’ for all that we learnt together on the Danube; and to a partner who shall remain unnamed- for being the key that unlocked the secrets of kizomba.

Finally, to Brenna Daldorph, who initiated me into kizomba in Paris, a massive thank you for being there from the start of this particular ‘never-ending story’

![Las Maravillas de Mali[2]](http://www.modernmoves.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Las-Maravillas-de-Mali2-1024x768.jpg)