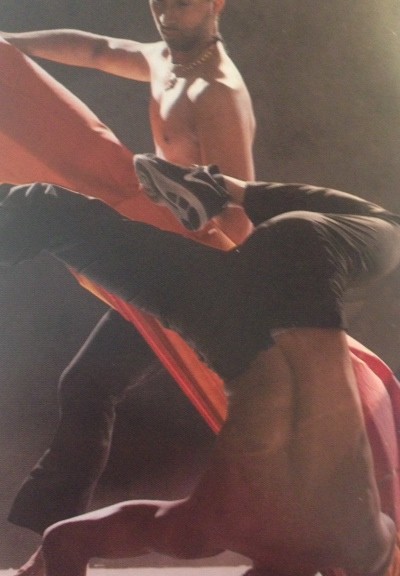

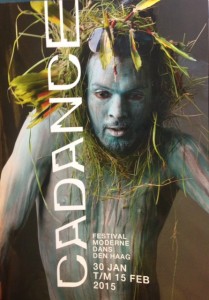

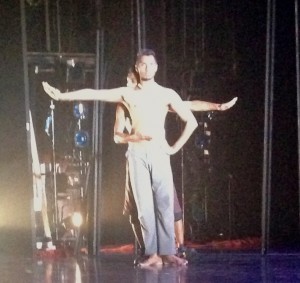

‘Grandparents’. ‘Suriname’. ‘Malaya’. ‘Rubber Plantations’. ‘Migrated’. ‘India’. ‘Australia’. ‘Utrecht’. These were the words that announced the presence on stage of two young men half hidden in the shadows—words that were fragments of two fragmented histories now sedimented in their bodies- their dancing bodies. Wrapped in an orange-gold silk sari that was at once placenta, straitjacket, security blanket, and creative inspiration, these Siamese twins conjoined by history now leapt, struggled, and contorted their bodies in a confrontation with themselves, their ancestors, their pasts, presents and futures—indeed time itself. When they broke free of this material, it was to initiate a movement-dialogue using their respective dance styles—bharatanatyam for Sooraj Subramaniam, and hip-hop for Shailesh Bahoran.

This was Material Men, Sooraj and Shailesh’s inspired collaboration for the Shobana Jeyasingh Dance Company, unfolding before my stunned (and tear-filled) eyes at the Queen Elizabeth Hall of London’s Southbank Centre.

Earlier this year, I had already enjoyed Lalla Rookh, Shailesh’s inspired intervention into the history of Indian migration using a moving combination of Afro-diasporic street dance styles and Indic ritual. That experience had convinced me that through dance there is indeed a way to link the African and Indian diasporas that empire and capitalism had triggered in waves— the diasporas from the African continent instigated by slavery, and the subsequent diasporas from the Indian subcontinent instigated by indentured labour. Shailesh revealed the universal address of the language of hip-hop and created new solidarities between diasporic cultures which, even though embedded in the same national and transnational spaces, don’t often collaborate or dialogue—except through dance. With Material Men, we went a step further in this use of dance to effect a meeting of histories, diasporas, and the oceans.

While Shailesh’s ancestors had migrated to Suriname from eastern India to work on the sugarcane plantations after the abolition of slavery, Sooraj’s grandparents had been part of the Indian diaspora that answered Malaya’s need for labour on the British Empire’s rubber plantations. They are the inheritors, therefore, of migrations across the Western and Eastern paths of the Indian Ocean and—in the case of the Indo-Caribbean diasporas, further across the Atlantic. Material Men’s use of Sooraj’s dance repertoire alongside Shailesh’s highlights two possible embodied responses to dance as liberation from this history.

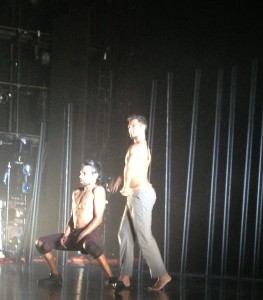

While Sooraj chose to train in the ‘classical’ styles of India, Shailesh took to an African-diasporic style. In Material Men, their dance styles bend, flex, and gesticulate like their bodies to respond to each other’s life path in dance. Bharatanatyam and hip-hop bleed into each other to create a new thing without a name, yet another witness to the continuous production of newness that ‘creolization’ indicates.

Of course, each dancer had already ‘creolized’ his chosen dance style through personal twists and interpretations before meeting each other. Shailesh has been using hip-hop to reproduce the robotic machine-metronome of Plantation time, while Sooraj’s pairing of traditional gold necklace with grey trousers and orange belt attested to his own creative take on a classical dance. Now, each with his own vocabulary struggled to make sense of history on a shared stage but in the process freed each other from their individual oppression by that history.

As the agility of Shailesh’s hip-hop met the raised palms, mudras, and stately postures of Sooraj’s bharatanatyam, the difficulty and exhilaration of the experiment was apparent. Starting out as antagonistic, ending up supporting each other, their sweating, breathing, and panting bodies embraced and intertwined and strained to converse while retaining individuality.

Different ancestral histories and dance trajectories notwithstanding, Material Men is the process whereby two dancers recognise and celebrate (not just mourn) their similarities grounded in modernity’s collective traumas of displacement and deracination. The sari that opens the show is the ‘material’ of histories of the heart — difficult loves and private domains that lurk beneath official narratives and their deafening silences.

The sari is the mother– ‘mother India’ with its heavy demand of fidelity to an idea of ‘home’ left far behind. Where and how does the diasporic subject find a toehold in that material/maternal vastness, always just out of reach? How does one acknowledge the caste-based oppression, collusions between colonisers and elites, and poverty that one’s ancestors would have fled, or indeed the adventure of new lives across the oceans (as is the story of Sooraj’s grandparents, who left India of their own volition to seek work)? Is turning to ‘Indian’ dance the answer, or adopting the styles forged by another diaspora?

Dance allows all answers to be right answers. The point about dance is that it allows a non-narrative freeing of histories that imprison. We talk of provincializing Europe but the need of the hour, which Material Men recognises, is to universalize Asia. The intimate chamber music composed by Elena Kats-Chernin that formed its score enabled this universalizing process, especially when, at a climactic moment, it was punctuated by the vocables of Indic dance. The heaving ribcages exposed by the dancers’ bare torsos, which radiated masculinity, fragility, labour, and beauty in equal measure, paid homage to another universal truth of modernity: the human body and its capacity to extract enjoyment and transcendence through labour and exhaustion. In Sooraj’s words, ‘there are moments in the striving for perfection that we forget to enjoy. In enjoying we get to just be, to embody, which is the true meaning of bhava. Shailesh and I were discussing recently that it is in enjoyment that the spirit of the dance is finally revealed. It is in that enjoyment that perfection, ananda, is attained.’

Material Men premiered at Queen Elizabeth Hall (Southbank Centre, London), on the 17th of September 2015, as part of a double bill by the Shobhana Jeyasingh Company. It continues on a UK-wide tour. Many thanks as always to Shailesh Bahoran whose work always inspires me to write, think, and feel better, and to Sooraj Subramaniam for making me appreciate the true beauty of bharatanatyam after a lifetime of being exposed to the dance.

All photos by Ananya Kabir (except feature image, taken from the event programme)