In August 2014, the Modern Moves team collaborated with London’s Batuke! Festival of Afro-Luso dance culture. This month’s Moving Story presents a kaleidoscope of our individual responses to the weekend, which included classes, parties, and participation in the Notting Hill Carnival on Monday.

Four very different perspectives here, which are not shy to reveal the intensely personal impact the festival had on each of us—and each one emphasizing the ‘exhilaration’ alongside the ‘learning’.

1. THE (JOYFUL) WOUND OF HISTORY- Ananya

Batuke 2014: In a basement room in central London, a group of dancers are going through the steps of the Angolan dance ‘Rebita’. The Rebita involves men and women promenading in a circle. When the ‘Commandante’ (here, the teacher Mestre Petchu) calls us to attention—‘atenção!’— we shift our steps from tempo to contratempo. Stepping into the circle with a crossed step, we shift back, face our partners, and flex our torsos towards each other. After this movement, we resume our Rebita promenade.

What we were performing in that group was the infamous gesture of ‘semba’— which Portuguese and other colonial authorities found the most scandalous element in the dances they observed amongst the Africans they encountered in the region that is now Angola, as well as amongst those transported to Brazil to work as slaves. It is a gesture that – despite this heavy weight of disapproval—has survived and lives on in various social dances across the Afro-diasporic world; it has even given its name to the modern dances ‘samba’ and ‘semba’.

A very specific experience that recurs in my dance research is the feeling, while I’m dancing, of being transported to another time and place. This uncanny encounter between my dancing body and a history that is not mine per se repeats itself often enough for me to not want to dismiss it as the product of an overheated romantic imagination. In the course of my research I constantly ask myself about ‘methodology’. What do we scholars actually do with social dance? How do we use living practice to reveal the past, and why should that past be of any importance and interest to the present?

The Batuke festival presented me with two moments of cutting through space and time. The first was the class in Rebita and Angolan carnival rhythms (such as kazukuta) that Mestre Petchu and Vanessa offered. An exhilarating session of men and women facing each other, led by Petchu and Vanessa; we moved by mimicking their gestures. The heat, the beat, the advance and retreat- the collective energy that warped the present- Petchu and Vanessa coming together briefly in couple hold to dance a few semba steps. I was somewhere in Angola, sometime when the rebita and kazukuta were transforming into semba.

The second class released a different energy. Kwenda Lima led a large group through Caboverdian rhythms: mazurka, coladeira, and batuke. As with the other class, we sometimes formed couples, sometimes divided into male and female groups. The atmosphere was defined by Kwenda’s mix of childlike joy and complete control over the archive he was opening. It was delightful to move from the mazurka, with its clear links to Central European partner dance, through the lively coladeiras and finally our fantastic finale of the batuke (more meaningful for us by being one of the songs in the Muloma soundtrack). Facing each other, keeping the rhythm by continuously slapping our thighs, we performed for each other, gave each other strength.

Once again I was translated to an ‘elsewhere’– an island in Cabo Verde, where women sang work songs and produced percussion out of their bodies—because they either did not possess percussion instruments, or because percussion was forbidden (as with the ‘patting juba’ traditions of the American South). That evening I discovered massive bruises on my thighs produced by the energetic batukeira that I had momentarily become. I remembered the wound that never heals on the ankle of Achille the Caribbean fisherman, in Derek Walcott’s epic poem Omeros? Yes, the wound of history– but also the mark of intense pleasure and a physical understanding of what it means to feel the batuque.

There were other moments, too, when the unexpected conjunctions of Afro-diasporic history passed through my body as participant and spectator. Jessica from New York paying homage to her Haitian heritage by dancing the yonvalou (voudou movement in honour of the snake god Damballa) at the start of her kizomba show with her dance partner Phil (also of Haitian heritage via Montreal); Nuno Campos and Iris de Brito teaching us to sing in Criolu (‘Sodade’) and Kimbundu (‘Muxima’), the sounds and words forming in our mouths and throats; all of us at the final class chanting in call and response format, participating in impromptu animations, and cheering on those who entered the drum circle to delight us with their quicksilver movements.

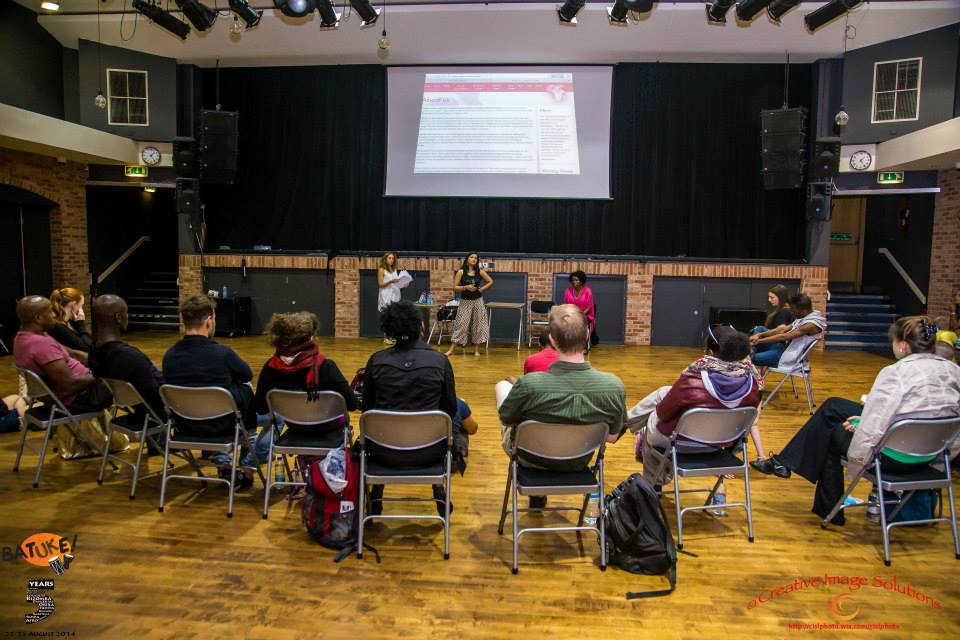

It’s unusual to find a festival that finds space for discussion, history, and reflection, as well as for dance pedagogy. When these elements are integrated into a festival it facilitates a different kind of learning experience. Dance and music illuminate each other in a mutually enhancing manner. The learning breakthroughs for me came in Phil and Jessica’s ‘kompa to kizomba’ presentation, and towards the end of Petchu and Vanessa’s seminar on Carnival. In the kompa presentation we were asked to dance in two-step to different genres- kompa, semba, zouk and merengue, while in the Carnival seminar, different couples danced social semba, funana, samba and carnival semba to the same song.

As each presenter asked members of the audience to dance to demonstrate the co-existence of similarity, difference and continuity, many things that I had only read about in texts suddenly came alive and made real sense.

2. ‘TIME GOES BY SO SLOWLY’- Elina

After a long weekend of dance classes and parties at Batuke! Festival in London from 22nd to 24th August 2014, anyone who has experienced so many different kinds of body activation would be both exhilarated and exhausted.

It was also an intensive brain ‘boot camp’ — as this word is now used in the dance context — that allowed me to experience and to think more deeply about how Afro-Luso dance culture, particularly kizomba, is now so popular among a very diverse range of people.

Besides the dance classes I attended, from Kwenda Lima’s Kaizen class to Coupé décalé (offered by an Angolan dancer by the way), from Rebita and Semba to Cape Verdian Mazurka and Coladeira, the parties taking place in the evenings were also a space where you could experience another relationship to dance. People are no more in training clothes and running shoes, but dress up according to the different themes (‘Union Jack swag’, ‘Great Gatsby’, ‘Miami Beach’), ready to apply on the dance floor what they learned in the day. The multiplication of possibilities to connect with dance in different ways during the festival allowed me to think about the complexity of spatiotemporal dimension in this frame.

As multi-layers of time are already entangled in the context of dance floors, the kizomba scene adds another dimension that could be related to the world of electronic music: the music is deliberately mixed in such a way that you can barely feel when a ‘song’ ends and another starts, especially during tarraxinha sets.

This also implies that the change of dance partner is not obvious at all and reshapes the relationships between the dance couple and the energy produced on the dance floor. You do not see a moving tide with hands and arms flying around like in a salsa party, but in the contrary, you can see a slow undulation of bodies, head against head with closed eyes, that seems able to never end. Indeed, if the dancers are both enjoying the dance, they can keep dancing without feeling any need to look for another partner for a while.

Thus I discovered during the Batuke! parties that some of the codes valid in the salsa world – for instance- are not accurate here. I am afraid that my ‘salsa’ tendency to move away from my dance partner at the end of the song was surely felt quite rude sometimes. You have to penetrate a world that is not only a space for a completely different kind of couple dance and music but has also its own rules. If you try to apply the ones you know previously without keeping this in mind and accepting your ignorance, you may be ‘chopped’ ¬or seem to ‘chop’ someone by mistake — to use a word from the Vogueing scene that I’ve learnt thanks to Madison!

Thinking about this phenomenon when we are used to dance according to a very specific setting which involves the change of partner after each song, then suddenly, discovering the possibility of being ‘locked’ with a complete stranger for about half an hour or more raises many questions: how the partners feel that it is the time to release each other? Who is responsible for ending the dance? Are both men and women feeling bad for being released only after one song? Besides, how important is the influence of the music production in this setting? Are the possibilities offered by electronic sounds ‘responsible’ for expanding the dance?

This slow dance, which is experienced by an international audience and could be considered, for many reasons, as a product of the globalization process in itself, thus confronts the realities of the globalized capitalist world where – in short – accumulation and speed are emphasized.

The notion of ‘song’ duration is transcended by the need of people to connect themselves with another body through the length of the dance. The longer the better to be completely immersed in a kind of transcendental space, where the two bodies are building a little story, song after song, without any words or even any eye contact sometimes, but with the sharing of a close body contact and the feeling of moving in a compatible manner.

My global assessment of the kizomba parties I first experienced so completely at Batuke is that they completely invert the balance between the couple dance part and the solo dance parts (on Afro House music) as I have experienced as a teenager during the first parties I ever had that we called ‘booms’ at that time. You were mainly dancing in solo but were secretly waiting for the ‘slow’ couple dance moment. At Batuke! parties, it seems that I had to forget all my expectations to be able to go beyond the dance culture in which I grew up!

3. ‘LAS PENAS SE VAN CANTANDO’- Francesca

Batuke! definitely represents an exception among the many festivals of kizomba, in terms of the effort to represent Afro-Luso culture in the most complete way and in terms of the quality of the professionals chosen for the event.

My impression of the teachers was really positive. I realised that they were chosen not just for the quality of the shows that they could produce –which is one common criterion of choice in this kind of event – but especially for their pedagogic qualities and their ability to move in a comparative way between different dances from the most traditional to the most modern ones throughout the Afro-diasporic world.

Some classes — the Kompa, Zouk, Coupé-decalé, traditional dances of Cape Verde, Rebita, Sabar — were really important opportunities to understand how the most contemporary dance evolved, and other activities like the seminars and the singing class very interestingly complemented this approach t o African culture and rhythm. I must say that very few organizers invest in the introduction of these elements in the dance festivals. Among the different classes that I participated in, I found the following ones particularly interesting:

New York Ginga by Jessica of Kizomba NYC: A comprehensive and interesting class by someone who was for me a lovely discovery through Batuke!. She explained basic movement technique for ladies’ ‘ginga’, starting form the opposition between chest and hips and the position of the knees, which is something fundamental to obtain the correct movement but that most teachers forget to explain. She then proceeded to the description of very simple movements as the frontal wave and hip rotation during the second basic, but she was able to deconstruct the movement to demonstrate very clearly the coordination between the changing of weight and the lateral step in order to make the process clear to even absolute beginners.

In the second half of the class, she applied some tango steps –following her own description of the work – to the ladies’ and men’s saidas. Despite my doubts about the fact that this kind of improvisation very hardly can work in couple dance and that very often women in kizomba have neither the time nor the occasion to plan correctly their own embellishments, the exercises were very useful to train quicker change of weight, balance recuperation, and a little improvisation using the contratempo.

What was evident to me – and it was also confirmed by the couple demo provided at the end of the class – was that the sequence could be applied only partially, and not easily, in a couple’s spontaneous interaction; yet it represented a very good training exercise. (video available)

Dancehall: This class brought together some nice movements that I recognized as belonging to very different African traditions. The typical traditional African movement of the hip circle was combined with the opening and closing of the knees– elements characteristic of some dances from the southern Congo areas that have evidently been developed in different ways in Jamaica adding to them the special cadence of ragga music and a deep bounce at the moment the movement is linked to another one. The basic ginga of capoeira was also used in the mini-choreography that we danced during the class, the basic step reproduced once with the original cadence and then twice at double the speed.

This dance beautifully demonstrated how Jamaican dances unify the idea of a fight with the idea of smooth and provocative movements that can use similar gestures with a completely different attitude. The teacher himself, Safwaan Ess Daboogie, said that he is constantly surprised by the presence of many heterogenic elements that he discovers in dancehall. Traditional kinetic codes are being constantly renewed in these street dances.

Singing: this class to me really represented the spirit of the festival: led by the teachers Iris de Brito and Nuno Campos we spent one hour trying to memorize and sing Creole and Kimbundu lyrics of the two songs Sodade and Muxima, and we received an explanation of the importance and meaning of the two songs that are really emblematic for the two cultures of Cape Verde and Angola. The experience was fascinating: when we try to reproduce the melody of a song in the singing we immediately feel our body interiorizing the rhythm and the cadence; consequently this starts coming out naturally even in the dancing gestures and in the posture of our own body.

Nuno’s explanation of ‘Saudade’ in Cape Verdean culture as a suspended moment, a calm but uncertain wait really clarified the Cape Verdean spirit and was maybe the most profound cultural topic that we touched: he described Sodade as an accepted sorrow, not dramatized, not desperately assumed, but the brief and intense sound of a drop, constantly falling over the echo of a wide but peaceful loneliness.

Final class: The best idea of the festival, and a moment in which we shared our own work and presence there, giving something back to ourselves and to all the group, to fellow participants and to the teachers, celebrating our own presence and energy. This final class has already become a classic and permanent element in the structure of the festival and is definitely a liberating moment in which people can experience the purest essence of dance and music. The dance can be improvisation on the drums, collective moment following a leader, or even just following with our own body the percussion without almost moving.

Dancing to the sound of live drums and without specific structure to follow is an experience that takes people to another level of interpretation of music and of their own movements. In the same way the experience of playing for somebody else for the first time is something really powerful that puts the dancer in a new position and stimulates new cognitive capacities of interpretation of the music and very physical conception of the rhythm.

Notting Hill Carnival: an amazing experience– one of those moments in which the body is part of the dance and part of the music and we can no longer separate them. People from all cultures participated and mixed in the event. We could recognize people that were not born into the cultural groups that paraded, wearing the same costumes with a sense of pride and love. I felt positively surprised by people’s capacity to embrace a new culture to the point of rebuilding the image of their own body and trying to live it in a new way. This was absolutely evident in the Brazilian parades, where people of all provenances were sharing the exhilaration of feeing the freedom and joy of their own body beautifully dressed and decorated, without any taboo due to aesthetical or social rules. It was truly a suspension of the common regular order and the opening of a new dimension in which the body seemed to surpass its limits and capacities and transform itself into a collective entity that was dancing shaking singing and screaming together.

This moment can be a very rich learning process for newer generations within a particular culture, since we actually experienced movements that were suggested by other people in the crowd without even seeing them, but just by means of the vibration of the bodies, without even knowing what our body was doing. Simply being part of a Carnival group is already a way to learn, and we learn by responding directly to the bodies of the other members of the group that impose on us their movement. The Batuke group was really full of energy and well organized and we danced in the rain for almost six hours without stopping. Nobody left till the moment when we decided to leave.

A very good experience was also the one of seeing represented the symbols that I discussed during my seminar on Maracatu on Sunday: seeing kings and queens opening the parade, Brazilian groups playing stick fights (Maculele), and having our own parade opened by an African folkloric group that had at their head a sort of joker figure with a very long stick pointing at the sky, decorated with colourful strips. Maybe he knew, maybe not, that he was recalling some unknown ancestors from another world, geography, dimension… anyway, we knew he was in the right place.

4. DANCE, RECOVERY, REDISCOVERY- Madison

As someone who can spend hours in nightclubs – so long as I’ve had an adequate ‘disco nap’! – during the Batuke! Festival I found myself experiencing a completely other sort of exhaustion. I participated in a number of classes, from Kwenda Lima’s Kaizen Dance and Cape Verdian Dances to Sabar from Senegal and AfroMix, but after each course, and sometimes during the middle of the class, I had to stop to catch my breath or sit out entirely. This was my first Batuke! Festival as well as my first hands-on exposure to many of these Afro-diasporic dance forms, and part of the incredible learning experience was staying in tune with my body, how it was moving and what it was telling me.

What’s the difference between dancing by yourself to music in a nightclub and being taught choreography as part of a group? How does the body labour differently in each situation?

The best class for me was the Sabar class, mostly because I loved the presence of the drums (and I would) as much as I loved the movements. The whole time there I kept thinking about Barbara Browning’s concept of ‘infectious rhythms’, where cultural transmissions occur through various types of ‘infections,’ with the powerful rhythm of the drum playing a key role. I loved the interplay between the dancer and the drums, with the dancer in many ways ‘conducting’ the drums. I noticed, too, that at the penultimate Batuke! Finale workshop, as each participant danced by the drums, there was definitely a sort of call-and-response, a direct communicative link between the body and the instrument, or the body as instrument.

If the dancer made smaller movements, the drummer made smaller sounds. If she or he made big movements, the drummer made bigger sounds. Certain sounds even lent themselves to all types of booty pops and pops, and this interplay between the body and the drum really made me think about the work a DJ does on any dance floor in inciting you to move, and to move in particular ways.

What I loved most about the festival was the sense of it being a shared space of learning and cultural transmission. People were there to learn. I bought homemade black hair care products and asked the person who sold it to me the best way to take care of my hair. But in terms of the dance itself I’ve already said that this was my first exposure to many of these forms, and even then I could already see how many of the moves percolate throughout contemporary popular music – and I’m thinking specifically of the global popularity of popping and locking, twerking, booty popping, grinding and all the rest.

But it was also a shared space for expressing one’s own connection to the diaspora. French, Spanish, Portuguese and German was spoken, in addition to English, of course. I was asked by several different participants ‘where I am from’, a question that most brown bodies are used to being asked. When I told folks that I was from New York, which is what I always say, the answer was never sufficient enough and people always dig deeper.

‘No, but what are your origins? What is your cultural background?’

And in that instance I say what I always say: my father, who I have never had any contact with, is Jamaican, and the rest is unclear. My mom made various kinds of curries and oxtail, culinary delights that in America are as much a part of Southern Style Soul Food as anything. I feel more African-American than anything as I have never really had any direct ties to Jamaican culture, not least because of rampant homophobia.

When I said this to one person in particular who asked me about my ethnic origins, she rightly told me that it doesn’t matter whether I feel any connection to the culture. It’s in my blood. The way I move and the way I dance is already impacted by my Jamaican roots because ‘it’ is in my blood.

The festival was also a shared space for experiencing connectivity and the universality of the human experience. More than one person I talked to emphasized the power of kizomba to highlight the feelings of being human. Though Kizomba does privilege heterosexuality and traditional gender roles, which admittedly I do have serious issues with, I did notice at least one lesbian couple, and another gay male I talked to told me that when he dances with a girl in kizomba, clearly for him he is not interested in a sexual experience but more in the spiritual feeling of connecting with another body. There’s something about being so in tune with another person that gives you an out-of-body experience.

Kwenda Lima’s exhilarating and fun Kaizen Dance class ended with an unexpected therapy session where his philosophy to life, as mirrored by the dance, was expounded on. Participants eagerly talked about their feelings, love, feeling free through dance, with some people in tears. Immediately I began wondering about the interplay between physical exhaustion, sweat, tears and confession all within the same dance class. How do all of those emotions relate together?

——-

Some questions are best answered by us performing the answers.

We hope this report has made you both think about dance and want to experience, whether for the first time or the hundredth, the exertions, exhilarations and epiphanies of the Afro-dance floor!

All photos courtesy of Kizomba United Kingdom.

The Modern Moves team thanks Iris de Brito for the opportunity to work with Batuke 2014.

This Moving Story was put together by Ananya Kabir on the basis of individual reports from Modern Moves team members Elina Djebbari, Francesca Negro, Ananya Kabir, and Madison Moore.