Sunday, 8th February, 2015.

Korzo Theater, The Hague: sunny afternoon outside, total darkness inside. Out of the dark emerge footsteps and the faint outline of bodies. Slowly six bodies, sitting cross-legged in a circle, are revealed. An Indian soundscape– tablas, Sanskrit chants— makes itself audible. A South Asian sacred ambience is unfolded through hand gestures that combine mudras, Islamic ablutions, and Hindu rites. We are in a meditative memorial space. Gestures that have become hegemonic in a majoritarian context are here, in double diaspora, as fragile and precious as a rose.

The bodies rise, their writhing movements around a single central box-like frame. The minimalist prop (which will stay on stage throughout the performance) is complemented by the outfits of the six dancers—short kurtas and dhotis of white homespun cotton—the signature garb of South Asian migrant labour down the ages. Beneath them we can glimpse the black stretch tops and leggings—the uniform of contemporary dancers. We are in a layered world. Here, bodies, space, sound, and movement bear witness to migration and mixing, to the subaltern’s labour that laid the bricks of modernity. This is the history commemorated in Shailesh Bahoran’s magnificent piece, Lalla Rookh.

Lalla Rookh was the ship that transported the first Hindustani emigrants from colonial India to the Dutch colony of Suriname. As the flyer accompanying the show reminds us, ‘the first group, consisted on 399 emigrants, came to shore at Fort Nieuw Amsterdam on 5 June 1873.’ As elsewhere throughout the imperial world, they came to fill the labour gap left after the abolition of slavery in 1863. ‘Between 1873 and 1916, over 34,000 Hindustanis chose to leave their homeland to go to Suriname to work as a field labourer or to work in the factories’. Bahoran and at least some of his multi-ethnic cast claim this history as their own. At the end of 50 minutes, Lalla Rookh leaves the audience with the realisation that all of us, subjects of late modernity, are also part of that history.

Lalla Rookh’s six dancers move from the particular to the universal through a versatile dance style with global reach: hiphop and associated kineasthetics (b-boying, breakdancing, funk, popping, locking). Afro-diasporic dance heritage here tells the story of the pagal samundar: Hindustani for ‘the mad sea’ that the ships encountered as they turned the Cape of Good Hope. Popping and locking suggest the ship tossed on high waves, and the dislocation of a body and mind in extreme agony. Whirling movements executed on the knees suggest incapacitation, even dementia. Two dancers lock their bodies; their crouching, swaying, and headstands remind me of capoeira. Battle steps forged through resistance on the slave plantation now enact the birth of the jahaji-bhai—the new camaraderie of the ship-brotherhood.

In this twilight of passage from the old to the as-yet-unknown, a young woman is wrapped in a sari and disrobed by her ship-companions. This extremely powerful sequence draws on the myth of Draupadi from the Indic ‘epic’, the Mahabharata. Draupadi’s kinsmen had tried to rape her in public by disrobing her, even as the god Krishna came to her rescue by merging his infinitude with her sari that consequently never left her body. But this is a new world; there is no Krishna here; the woman writhes as her sari is ripped off. A male dancer whirls it around his body in a mad frenzy; the sari becomes the ship’s sail. New myths for old: Rape, brutality, and the violence born of violence constitute the jahaji-bhai’s baggage.

Darkness.

Landfall.

The remainder of the production uses hiphop and urban dance to evoke the complete transformation of the new arrival to what, in the Fijian context, was called the ‘girmitiya’ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Girmityas: the subject of Empire whose body is worth the labour it is contracted to deliver, measurable in years, months, days, and hours. The soundtrack highlights this extreme measurement of human worth by capitalist time through the predominance of a metronomic ticking clock and the dancers’ breathtakingly accomplished body isolations. These movements peak into a long sequence of body shudders to a percussive line that becomes increasingly industrial and machine-like. These are the Robots of the Plantation and the Factory, the zombies of the Caribbean imaginary, the cogs in Capitalism’s monstrous wheels.

Periodically, melodies and chanting voices revive a sense of the sacred. Fragments of a thumri in a minor key are interspersed with atmospheric crackles. An existential problem emerges: how to heal through these fragments? Can the trauma of Lalla Rookh and kala pani (black waters)— the dark passage that robbed one of identity and moorings—ever recede? The box-frame that signified the ship is viciously and urgently rejected. But it never leaves the stage. The suggestion is of identities lost, but new ones born— without amnesia. This is why a New World dance vocabulary, forged through the embodied experiences of those who had been displaced earlier by slavery, makes such poetic sense here.

Yet Indian-ness persists in the little traditions that Lalla Rookh lovingly celebrates. The ritual gestures of meditation and prayer return. The labourer who dies after an all-consuming burst of physical rebellion and exhaustion is anointed on top of that same white box-frame. His companions consecrate his body with drops of water shaken from fresh leaves dipped into small ritual vessels, in the same way as his ancestors would have done in the plains of India’s great rivers. As the five remaining dancers circle the prone body in course of the ritual, their sobs mingle with the already layered soundtrack. I wonder—is this the end? Let there be something else. Please.

Suddenly, thankfully, we get the release we crave. A series of shudders unite the group and transform into a burst of triumphant movement. There are many deaths in the piece, but there are rebirths, too. And what is reborn is a new creolized body— with Indian hand mudras and b-boying lower bodies, with relentless metronome of Capitalist time overlain by the lovely notes of the wooden flute—Krishna’s flute— carrying the essence of Indic sweetness across the mad seas. As I resurfaced in the minimalist foyer of the very Dutch Korzo Theater, blinking away my tears, my understanding of the Netherlands’ inner history and its hidden connection with my own postcolonial Indian-ness was once again expanded— in a process that started when I visited Suriname a few years ago.

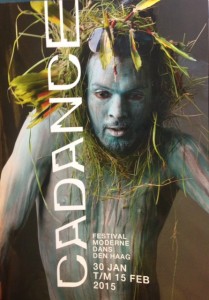

From the CaDance Festival brochures, banners, and website, an arresting figure has been watching us. It is Shailesh Bahoran himself, a contemporary Amazonian river-deity rising from the edge of where Plantation meets Rainforest (or so I imagine); painted blue like Krishna, wreathed with feathers and grass like a mythic figure from a Wilson Harris novel; sunglasses jauntily proclaiming his swag, and body arrested in a ribcage move that is typically Afro-diasporic. This palimpsest of a body is what Suriname, one of the most culturally and demographically mixed up places in the world, brings to our consciousness. We are all more or less like that body. It is the labours of that body to which we owe the modern world. The search for culture is now conducted through a creole language. And we all must learn to speak it, recognise its fragments within us, treat it with love and respect. That’s what Lalla Rookh‘s visionary director and its superbly talented dancers teach us.

Thanks to the dancers and director for a wonderful and moving theatre experience!

All photos of the Lalla Rookh performance courtesy of Shailesh Bahoran

All photos of Paramaribo, Suriname, and final photo of the CaDance brochure courtesy of Ananya Kabir